Ulises Carrión 2: Including Selections from the Collection of Guy Schraenen

Jonathan A. Hill Bookseller Catalogue 245 , NY 10023

Writing critically and descriptively about a sale catalogue might seem odd, except that this work of expertly researched materials provides an opportunity to say something about the ways history gets made, brought forward, and codified through such publications. This presentation of works by Ulises Carrión was assembled by Yoshi Hill of Jonathan A. Hill, Booksellers, who obtained much of the material from the collection of the late Guy Schraenen, a friend to Carrión who was also an archivist and publisher of avant-garde and small press materials. Given the focus on a single artist, the work is highly specialized. But the catalogue demonstrates how important these fragments of cultural history are for understanding the activities of an artist within their network of connections and milieu. Here we have evidence, rather than narrative, though the descriptions supply a generous amount of information about Carrión and his life.

Other Books & So catalogue, 1976

Ulises Carrión is a somewhat mythic figure within the history of artists’ books and conceptual art of the 1970s and 80s. Born in 1941 in Mexico, Carrión died in Amsterdam in 1989. With his partner Aart van Barneveld, he was the co-founder and organizer of Other Books & So. The shop occupied two different venues on the Herengracht in central Amsterdam, both modest in scale and enormous in profile. When I arrived in Amsterdam in summer 1978, this was one of the first pilgrimage sites I visited. It was near the Drukhuis, another short-lived and very Dutch seeming (to my American mind) institution, funded as it was to provide access to letterpress equipment and materials. I printed two books at the Drukhuis, lodged in a vintage (likely 17th-century) three-story brick house which, like any building in the old part of the city, had settled into the uncertain foundations with a crooked house-that-Jack-Built out-of-kilter relation to any strict horizontal or vertical dimensions. The issues this caused for levelling presses can be readily imagined…But back to Carrión. His bookstore-gallery was staged (I used the term deliberately since the modest décor was so carefully considered in every detail) in what I remember as a whitewashed cave space, very contemporary and minimal. I was suitably impressed and intimidated. Carrión was an already-well-known figure and I was a little sprout.

Carrión had been a rising star of the literary scene in Mexico before he relocated to Amsterdam. The publication of several short stories in major mainstream as well as independent Mexican journals is documented by the facsimile covers and notes in Hill’s catalogue. From this and other entries we track the trajectory of Carrión’s travels, career activities, and various engagements with conceptual art, performance art, video, and of course, artists’ books and publications.

Carrión was light in presence and spirit. He was mercurial, small and lithe, with vibrant energy and sense of levity. In the artists’ book community, his publications had an enormous influence. His manifesto, The New Art of Making Books, appeared in 1975, the same year he opened the first venue of Other Books & So. A year later, in 1976, Printed Matter opened, a still-operating artists’ book store that was founded by Lucy Lippard, Sol Lewitt and others of substantial pedigree associated with conceptual art in New York. While the idea of artists’ books in the contemporary sense is often linked to the publication of Ed Ruscha’s Twentysix Gasoline Stations (Los Angeles: Heavy Industry, 1963), the term and the concept became codified by these bookstores and writing practices in the 1970s. Carrión played a significant role through both, as well as in his own performances and artists’ publications and many of his important critical writings have been republished posthumously in The New Art of Making Books.[i]

The Wiki page devoted to Carrión notes in “Recent Reception” that the significance accorded to him is perhaps “due to a certain cult of the overlooked and underestimated (post-) 1960s avant-garde.” But that perspective, like any judgement of value, depends very much on the place from which the assessment is being made. Though it would be hard to grant Carrión the stature of figures now in the conceptual pantheon (with all the problematic dimensions of such a notion), his contribution had a unique and lasting impact in developing the concept of the artists’ book in its formal, procedural, and critical aspects. And his own artworks and publications had a distinct quality, combining visual poetics and procedural mark-making in a sleight of hand and mind production. Again, these are light works, slim small volumes, even when their thematics touch on serious matters, as in his final hand-drawn objects.

The catalogue is an exquisitely produced collection of facsimiles of the materials the bookseller is managing. The care with which the presentation has been put together and the production values in design, printing, photography, and expertly meticulous cataloguing make it an exemplary piece for study. As noted, a sale catalogue presents individual items, rather than embedding the objects within a narrative. In this regard it is radically different from an exhibition catalogue where the critical discussion frames the works. In this presentation the artifacts are foregrounded. They justify their value through the implied narrative of a life and career of which they are the remaining evidence, but also, they are presented for their material richness and authenticity. While many interesting points can be made about Carrión’s practice and his life (and are in the descriptive entries, so that we get a good sense of his movements and profile) the pieces themselves are what matters. The catalogue draws on the (clearly acknowledged) work of Maike Aden and Guy Schraenen in their publication, Dear reader. Don’t read, an extensive publication that accompanied a major retrospective at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia in Madrid in 2016.[ii] This is a key reference for Carrión and Schraenen knew the artist well. They had many shared connections and areas of overlap through his own Galerie Kontakt and other activities. Several years after Schraenen’s death, Hill acquired the collection of Carrión’s work, and these lineages of intellectual, curatorial, and critical connection underpin this publication.

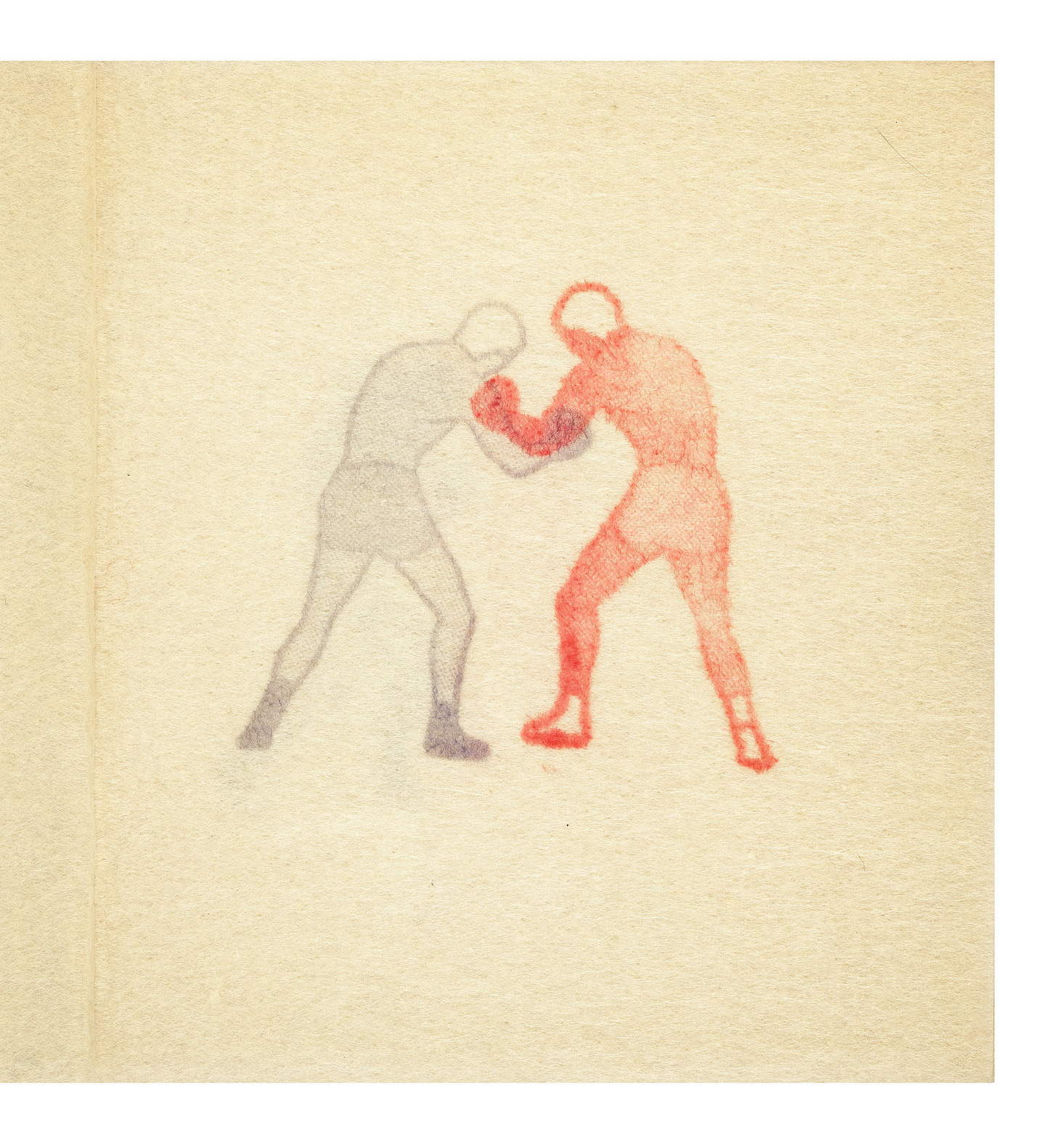

Mirror Box 1979.

The first image in the catalogue is a reproduction from Mirror Box (1979), a work with red and black ink on soft quasi-translucent paper. Two male figures, printed from rubber stamps, face each other in shorts and gloves, looking more like dancers than fighters in their gentle stance. This minimal but nicely deformed approach is characteristic of Carrión’s work, his way of working lightly and deftly to shift the meaning and effect of an image or word. Again, the striking care with which the catalogue is produced is important. The reproduced page bleeds past the edges, and thus, is presented as if it were the original, not an image of it.

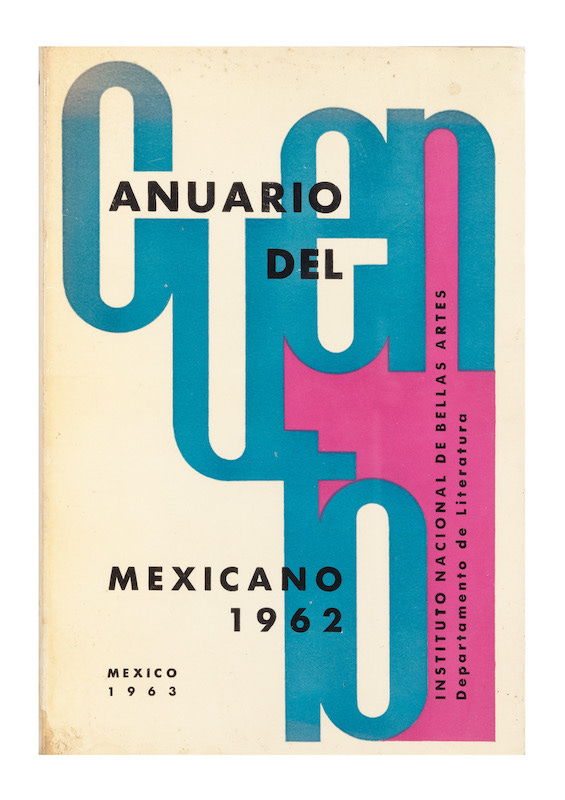

Annuario cover, 1962

Revista, cover, 1962

Most of the items are reproduced in small-scale facsimiles of the individual works, in standard catalogue format. Still, every image sings with the material richness of the originals. The first authored texts, Carrión’s early output in Mexican literary journals, are represented by the covers of these publications. The polished, notably mid-century modern cover design of Anuario del Cuento Mexicano 1961 makes a nice contrast with the modest, letterpress typography of the experimental literary journal Revista Mexicana de Literatura, November December 1962. Independent publishing is always conspicuously underfunded while the Anuario’s fluid organic forms and strong colors are stylishly contemporary. These material details are eloquent, and Hill’s catalogue provides visual access to them.

The characterization of Carrión’s approach to literature is succinctly expressed in the phrase from his 1976 Contents exhibition catalogue. He states that whatever genre—short stories, theater plays, or poems–he uses he considers “manifestations of language, as autonomous structures.” (p. 28) Such attention to the thing, to the object-ness and properties of language, was a through-line of critical thought from the early 20th century avant-garde (e.g. Russian formalists) through mid-and-later 20th-century and current conceptual writers. Such work is far from the lyric, with little or no commitment to interior life, its expression, imagism, symbolism, or other movements. I mean this descriptively, not judgmentally. The catalogue entries comment on a collection of his works La Muerte de Miss O (Ediciones Era) in a similar vein. His literary reputation was growing in Mexico, but the work “foreshadows his rupture from the literary world of Mexico and his growing embrace of Structuralist theory and the visual arts.” This is echoed in his declaration, “A play is a structure,” mentioned in Maike Aden’s 2016 article “Carrión Carries On.” (JAB: Journal of Artists’ Books, No.40). (p.20). Form leads. Content follows.

Not surprisingly, therefore, material details are given emphasis in Carrión’s works. So the reproductions of samples from his sister’s and parents’ rooms in Tell me what sort of wall paper your room has and I will tell you who you are (In-Out Publications, 1973), need the visual precision the catalogue affords them. Likewise, the physical quality of typed carbon copy sheets is palpable in the image of his master’s thesis, Judas’ Kiss and Shakespeare’s Henry VIII produced at the University of Leeds in 1972, and in the signed and counter-signed contracts with Ediciones Era on tinted paper, with letterhead and logo. These mimeo sheets and their signatures were contracts for his first and second books, both collections of short stories. Other autograph materials are also presented, such as the 1973 manuscript for Amor la palabra, written in Amsterdam. The beautiful soft lined paper in the interior of the notebook feels fully present, as do the words handwritten in bold ink “para aart / que estudia filología,” a dedication to his partner who was studying philology.

In some regards, the items in the catalogue might be somewhat fetishized. This has been true for awhile with Carrión’s ephemera and output. But it is exactly the minimal lightness, the ephemerality, of many of these objects that gives them, paradoxically, their weight. For what is so often lost in artists’ archives are items like the hand-torn announcement of an exhibit, a flyer, a postcard for an opening, and so on. Many of these were produced using inexpensive available means—typewriter, mimeo, and offset. A handful have hand-set typographic covers or even interiors, but, that, too, in the 1970s, meant a readily available means of production that did not require intensive capital investment. This is significant since the production is an index to the position this work occupied within the economic systems by which value shifts over time. And the range of production is engaging—IBM Selectric, carbon copies, hand written, typewritten, and even—amazingly, a hand-set letterpress edition of 6 Plays produced in 100 copies at the Drukhuis by the artist-writer Michael Gibbs and John Liggins for Kontexts Publications. (p.66) Each of these productions speaks to the conditions of making within a larger economy of artistic culture of the period.

Finally, the value of this catalogue is not only in its presentation of the work of a much-respected artist, but in the preservation of the fabric of culture, of aesthetics, of artistic communities and lives. The four catalogues for Other Books & So, issued between 1975 and 1977 would be invaluable for research. The network of people who connected with Carrión is fascinating—Alan Kaprow, Dick Higgins, Takaka Saito, Richard Kostelanetz, Anna Banana and many others (p.60-61). At one point, Carrión invited 1000 artists to send their books—provided they were only “what you make,” in other words, not commercial or publisher-driving works. A look at that mailing list would be revealing. Other intriguing artifacts appear as well that document his “Dutch Art Fair Language Performances 5 April 1977” (p. 77), a small exhibition catalogue for Galeria Remont in 1977, its staples showing along the spine, giving a concrete sense of its dimensions. In 1977, he issued a Fundraising solicitation for Other Books so they could move a few doors from Herengracht 227to a larger space at 259 Herengracht. These details of economy and business contribute to the story of alternative culture at any period, as do those of the who-was-who among the many presenters and performers. Writing the history of culture through networks and communities, now becoming a more common mode with the use of digital tools, depends on the availability of original resources from which to construct it. Here is a small treasure trove of such resources.

Missing Piece, 1988.

The last items in his output, the unique, hand-drawn books that were his final productions have a deeply moving quality to them. With its dark gestural strokes across translucent sheets, the 1988 work, Missing Pieces, reads as memento mori in advance. The velvet-y black curves, long swashes of thick graphite fading across the strokes, are striking in their combination of simplicity and eloquence. These cut across sheets from which a rectangle has been strategically removed. These absences, read against the vital gesture of the marks, say nearly everything that needs to be said about their elegiac force. (p. 128-131). As in so much of Carrión’s work, the minimal quality intensifies the value of what is present, forcing the mind of the reader to focus on what is there, without distractions, and with an absolute clarity about how form matters. The ephemerality of life is embodied in the fleeting moments of which these pieces are all evidence. That may be one of Carrión’s lasting gifts, the ability to make us pay attention to that fact—with no heaviness in the recognition, no maudlin sentimentality, only a lightness and grace.

Thanks to Yoshi Hill for permission to use the images.

For more information: [1] https://www.jonathanahill.com/catalogues.php

Note the forthcoming exhibit: Ulises Carrión: Bookworks and Beyond, 21 February-16 June 2024; Ellen and Leonard Milberg Gallery, Firestone Library, Princeton University; Curated by Sal Hamerman and Javier Rivero Ramos.

[i] I have found various citations of editions of this text: The New Art of Making Books (Nicosia: Aegean Editions, 2001) and (Mexico City: Tumbona Editions and the Mexican Ministry of Art and Culture, 2016) and “Quant aux Livres,” (Geneva: Editions Heros-Limite, 2008). The manifesto has been translated and published in multiple places. As I don’t have access to these, I can’t verify the details.

[ii] Dear Reader. Don’t Read. https://www.museoreinasofia.es/en/publicaciones/dear-reader-dont-read