The Intelligence of Noah Davis

Exhibition at the Hammer Museum, UCLA, Westwood through August 31, 2025 https://hammer.ucla.edu/exhibitions/2025/noah-davis

Noah Davis (1983-2015), who died at the age of 32 from a rare form of cancer, left a definitive corpus of works in a range of documentary, personal, and conceptual modes. He was a painter of the scenes of life around him, mainly but not exclusively, in Los Angeles, and drew directly on observation and experience as one basis of his work–along with using extensive collections of photographs and other source material. Describing Davis’s work in isolation is far less rewarding that seeing it in dialogue with his contemporaries as well as placing it within the long history of American scene painting. Continuities and connections feel deliberate in Davis’s work, as he borrowed as well as invented, adopted and transformed even as he innovated, but clearly within an American idiom.

From the 1890s through the crucial decades of the 1920s and 30s, up to and through the beginning of World War II, the predominant trends in American art clustered around the production of a visual record of modernity and modernization—the coming of age of America in its urban and industrial strength and transformation of the rural agrarian nation into a global financial and political power. That work included many groups of artists—the so-called “Ashcan” group in New York, the Regionalist painters, and those affiliated with Social Realism.[1] Among these were outstanding African American artists Horace Pippin, Aaron Douglas, Romare Bearden, Ellis Wilson, and Beauford Delaney, to name just a few of the most prominent. The crucial argument is that American art became modern in style, outlook, and iconography through its engagement with the changing cultural conditions of the country as they were embodied in the transformation of its land and people, social relations, and events.

This kind of American realism was largely eclipsed in the second half of the 20th century as prevailing mythology about the “triumph of modern art” promoted the work of the New York school abstract painters—Jackson Pollock, Barnett Newman, Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still, Willem de Kooning and others in the pantheon of the period. Jacob Lawrence’s 1941 Great Migration Series and Edward Hopper’s 1942 Nighthawks appeared just as this change of fashion was taking hold. But in general, American scene painting was deemed provincial and its claims could not match the aspirations of a generation that came to signify the individual and national ambitions of the period. Interestingly, images of daily life in urban and rural and circumstances never disappeared, showing up in film and literature (Raymond Chandler, Carson McCullers, James Baldwin, Raymond Carver, for instance) as well as the domestic settings that proliferated in the emerging world of television broadcast.

However, for several decades after the 1940s, painting became focused on what the high-profile critic Clement Greenberg defined as the essential feature of “modern” art–the surface of the picture plane. The successive waves of movements and –isms occurred before the so-called “return of figuration” in the 1980s. In actuality, scene painting never went away, even if was largely practiced by women and people from communities in which self-representation and attention to the immediate surrounding world remained compelling.

This prelude is meant to situate Davis within a longer tradition and wide set of affiliations. For Davis is a singularly self-aware artist. He uses style, technique, and imagery to cite and then differentiate himself from the broader field. Faith Ringgold, Kerry James Marshall, Robert Colescott—all artists with whom Davis is in clear dialogue—are also painters of Black experience in America. But where they each develop(ed) an identifiable style, part of Davis’s virtuosity is his ability to make each painting distinctive. By contrast, Davis has a historical imagination and seems to conceive his work within a situated perspective of precedessors and contemporaries.

As an example, take the first picture in the exhibit titled Forty Acres and a Unicorn (2007). The irony of the title is borne out by the fantasy of the image, but the deliberateness of the treatment gives it the gravitas of a dream that is eerily real. The animal and young rider are isolated in the small canvas, and the image is painted with a elaborate opacity, as if to materialize the fantasy in an irrefutably solid surface. This early work could easily have been the stepping stone to more fantastic imagery, but instead, it is the opening gambit in a series of works rooted in external observation and innovative citation rather than internal reflection. The painting is hung by itself, which also gives it a gravitas its relatively small scale might not have accrued if not for the thoughtfulness of the Hammer’s installation.

Forty Acres and a Unicorn, 2007

Take as a second example the much more commanding, magnificent Mary Jane, painted a year later. Davis uses an impasto pattern of foliage to foreground the child who is also a lone figure. The intense animism of the ground is reinforced by the play of positive-negative shapes, which alternate in assuming solid form. Sunlight or leaves? Spaces between the branches of a hedge or bats? The scene almost threatens to overwhelm the girl, who seems vulnerable in spite of her solidly straightforward stance. Shades of Goya’s The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters are suggested by the imagery, but other references also come to mind–such as the patterns so often present in the canvases of Horace Pippin who uses them as a foil for his human figures. Images of children appear often in Davis’s work such as the girl in Single Mother Father Out of the Picture (2007-08), or child being spanked in Bad Boy for Life (2007), and the 2004 painting of a 1984 photograph of Davis’s wife Karon in a terrifying Holly Hobbie (white face) mask. In the first he plays with a photo-realistic genre with touches of Norman Rockwell. In the second, he could be borrowing from the flat compositions of Charles Sheeler’s interiors from the 1920s through his meticulous attention to the details of material objects and textiles in the room. In the third, he is using the striking force of German Neo-Expressionism to intensify the impact of the imagery.

I would suggest that every canvas in this exhibit shows a similar process of deciding how to paint, not just what, through a considered inventory of available possibilities as part of the process. This is not to suggest that Davis is a derivative painter, not in the least, but instead to emphasize the situated-ness of his visual imagination.

Mary Jane, 2008

Davis’s work is compelling on many levels, not least of all because of the painter’s love of what paint can do—drip, layer, veil, glaze—and how compositions work to structure the viewer’s experience. Almost each painting would reward a detailed reading. But it is the continuity Davis demonstrates with the long tradition of American scene painting that is of particular interest—even as he keeps his work fully in dialogue with contemporary work. Davis is not nostalgic, and the painting is not retro or backward looking, instead, it renews the engagement of art and experience. Still, the shadows are there—George Bellows scenes of boxing do not lurk far beneath the surface of Davis’s studies of daytime television. Hints of Douglas’s Migration and Bearden’s graphic style are evident in Davis’s riding a line between abstraction and figuration. Bits of John Sloan surface in the urban settings while Charles Eakins seems an unavoidable reference for some of the images of swimmers. All of this is interesting as an argument for the value of that once set-aside tradition of American scene painting.

Perhaps that work no longer needs defending, but at a certain period, between 1989 and 1994, I taught modern art history at Columbia University. The department was typical for the period, a faculty of senior white men, a handful of women (chiefly in non-Western fields), maintained a deep commitment to both the canon of Western art and the traditions of connoisseurship within which the field had developed from its German origins. Critical theory, semiotics, post-Structuralism, feminism, and any of the other newer approaches to cultural criticism and interpretation were highly suspect, and I had been hired in part because I was conversant in these heresies for which the graduate students, at least, were eager. But if my “Theorizing Modernism” course was tolerated as a concession to the emergence of “new” theory, my interest in early 20th century art was treated with derogatory dismissal. Modern art had been European until the end of the Second World War and then became absolutely and irrefutably American after. That was the standard line in the field as a whole. American landscape painting in the 19th century had a place because of the Hudson Valley painters and the exploration of the American West by Europeans who created landscapes in the Romantic mode. But American scene painting? The work of migrants and immigrants? The depiction of the building of New York? Views of laundry on the line in a tenement? Trombone players and other jazz musicians? Tight-lipped American farmers rolling fields of grain? Boxers, bridges, skyscrapers and lonely office workers? All this bordered on kitsch, my Greenberg-subscribing colleagues asserted.

“There is no good art in America in that period,” was the single sentence passed on my proposal for a course on American art from 1890 to 1940. I was young, untenured, and bold and so taught the class several times to rapt and eager students who may not yet have seen the future crumbling edifice of art world mythologies and rigid historical orthodoxies, but did see the value of the ways these works showed how America had become modern, not just how modern art had become defined around abstraction and the claims of the avant-garde. The language of American modernism was also an invention, its loose strokes, bold colors, stark forms, transforming the physical world into a vivid vocabulary of subjective observation. But observation it definitely was, and the record of experience rendered in graphic terms that were far from those of academic realism or soft-focus impressionism was as innovative and as integral to American communities as scenes of rural life and urban change.

My passion for the work of that era has never dimmed, in part because it is so uniquely American in its range of influences and styles—Caribbean colors, Midwestern palettes, ethnic patterns, an increasing attention to flat surface and materials, the use of poster and print techniques, the attention to source materials from living and diverse communities. So much can and perhaps by now has been said of the work of those decades. But Davis’s attitude feels deeply connected with that tradition, respectful of what it offers as models of engagement with the intimate world of family, home, and community, and speaks eloquently about aesthetic continuity and vitality.

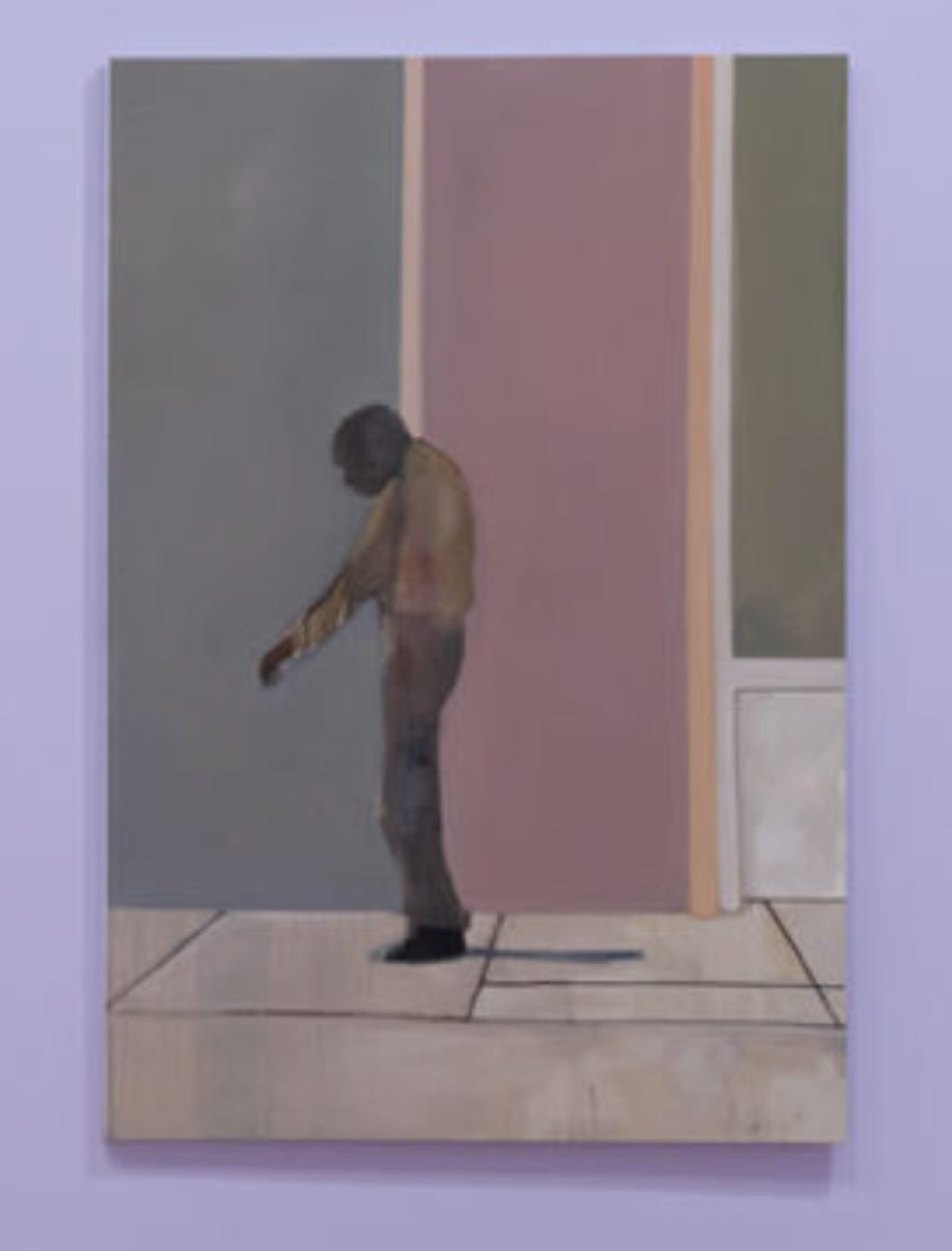

Untitled, 2015

Not only did I love this exhibit, but it literally made me cry. By the end, looking at a 2015 painting of an elderly man whose body is becoming transparent in the transition between life and death, I felt the immense sadness of entering into that phase of human existence. No doubt for Davis this was a time of coming to the full realization of his own demise. The impact of Davis’s work does not come just from the knowledge of how short his life was, but that fact is still inescapable. Would the final paintings in this exhibit read differently painted by someone still living? Perhaps.

But, to reiterate, the critical dimension to Davis’s work that makes it stand out is his acute capacity to make use of references and situate his own canvases within them. One image with a smeared grey ground, for instance, echoes the blurred grey scale photographic images painted by Gerhard Richter. Using that contemporary reference, Davis recasts the American scene image (of a child levitating among a group in a playground) into a dialogue with contemporary New Figuration and European Conceptualism. The intelligence of this work is indisputable, and visually present.

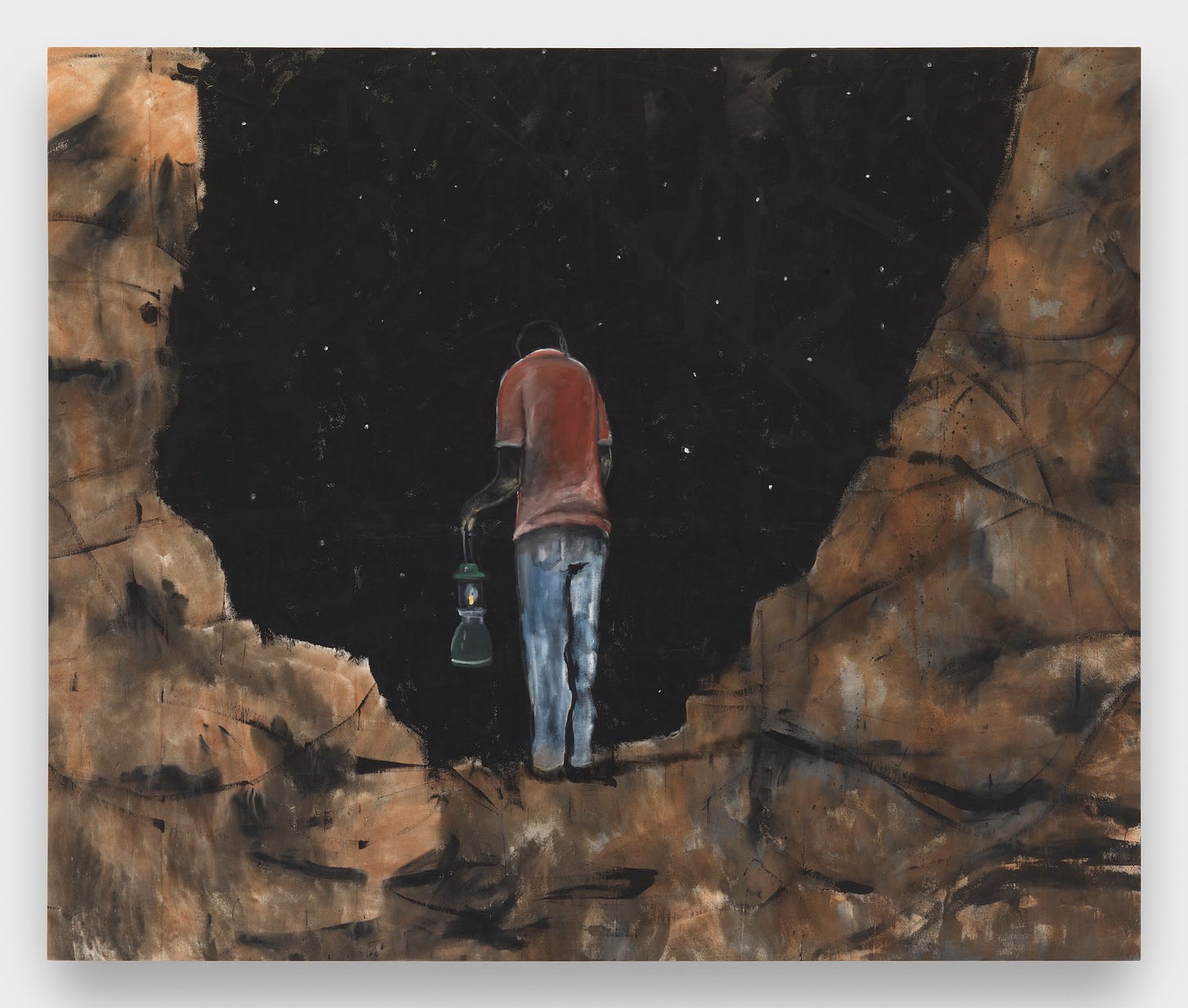

Painting for my Dad, 2013

The same argument could be made for many of the images on exhibit, but one more will have to suffice, the Painting for my Dad, 2013. The iconography of a single male figure staring into the abyss immediately recalls Caspar David Friedrich’s The Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818). Davis’s sure strokes and rough treatment of the rocks that frame the starry sky are virtuousic painting, deliberately loose and painterly putting the focus of the memorial tribute to the spirit of his father on the man himself, holding a lantern. Both Friedrich’s and Davis’s paintings rhyme in an interesting way with Gustave Caillebotte’s Young Man at His Window (1876) in which an urbane gentleman stares out at an indisputably cosmopolitan scene. In all three images, the back of the staring figure gives us information about age, demographics, circumstances and so on through their posture and dress as well as their situation. The striking similarity of the compositions emphasizes the differences among the aesthetic arguments each makes.

By invoking these references, Davis calls attention to the crucial fact that all works of art are created in relation to others, wittingly or not. No painted image or creative work comes into being without being situated within the broad historical and contemporary field, and Davis, I would argue, makes that point through his canvases, but also, through the wry irony of his citation of conceptual and hard-edge abstractions, some of which were part of his Underground Museum project with his wife, Karon Om Vereen-Davis. His winks and nods at the rule of art institutions is another gesture through which he signals his understanding of the ways works of art acquired meaning through circulation. No work can be read outside of these historical and cultural frames of reference, a point of which Davis makes us acutely aware.

This exhibit is on view at UCLA’s Hammer Museum through August 31, 2025. Really worth a visit.

[1] The group around Robert Henri included William Glackens, George Luks, John Sloan, and Everett Shin as well as Reginald Marsh, George Bellows, and Louis Lodzowick. Renowned Regional painters were William Hart Benton, Grant Wood, and John Steuart Curry. Prominent Social Realists were Moses and Raphael Soyer, Ben Shahn, and Paul Cadmus.

Fascinating review. Wish I could visit the exhibition.