Reading Meret Oppenheim

The iconic Surrealist sculptures produced by Meret Oppenheim in the 1930s have the unmistakable stamp of feminist imagination. Her (possibly) most famous work, the fur covered cup and saucer (Object, Déjeuner en Fourrure, 1936), positively resonates with gendered associations. Her intimate suggestivity references pleasure, consumption, mouth and private parts simultaneously. Others may read it differently, but my response has always been to see the transformation of the ordinary object—cup and saucer—into an extraordinary one as a eroticization of its identity. As in the case of any fully realized work of art, the piece never finishes for me, never exhausts its capacity to evoke a reading, again, of its combination of formal, material, conceptual, and aesthetic properties.

In addition, the work is legible within a historical lineage, readily placed. This is not a piece that could have been made before the 1920s. No 19th century sculptor would have thought in terms of such transformations, even if the painter Odilon Redon or poet Charles Baudelaire (among others, of course) might have made suggestive allusions in their work to metamorphosed hybrid objects and engaged in erotic provocations. Redon and Baudelaire, as well as Arthur Rimbaud, are useful touchstones in the discussion of Oppenheim for their vocabularies, visions, and syntactic disruptions of painterly and poetic forms. More on this in a moment. Returning to the cup, again, and its historical specificity, the use of materials signals its moment of production. Sculpture in the 19th century in Europe was made of marble, wood, bronze, stone—the traditional, durable, stuff from which carved and cast artifacts had been produced for decades. When Edgar Degas added a tulle skirt, wig, and wax coating to his Ballet Dancer of Fourteen Years (begun around 1880), he was bringing methods from folk and religious art into the precincts of fine art. The example was rarely followed until works Cubist and Dada assemblage began to appropriate all kinds of stuff into the production of sculptural objects. At the same time, formal approaches pushed early 20th century modern artists into distilled sculptural elegance (e.g. Constantin Brancusi), the non-representational vocabulary of Constructivists (e.g. Naum Gabo), and sophisticated abstraction of Futurists (e.g. Umberto Boccioni). Among the quintessential works of the 1910s-1920s were the Prouns produced by Lazar El Lissitzky between 1919-1927 whose use of geometric shapes, mechanical motifs, and novel materials spoke volumes about the search for modern forms. These geometric abstractions practically defined modern sculpture, giving it a distinct identity unlike any works of three-dimensional art of the past in Western—or other—cultures.

While the claims to universalism, the investigation of formal methods as a way to discover a “language of form” outside of history or culture, turned out to be as culturally and historically circumscribed as any other approach, the point is that the work of the trickster conceptualist, Marcel Duchamp, as well as various Dada and Surrealist artists first working in the 1910s, registers within frameworks where a formalist paradigm had taken hold. Oppenheim’s cup and saucer, like Duchamp’s Fountain, the infamous upturned urinal exhibited in 1917, were not conceived in response to 19th century sculpture–Auguste Rodin, Camille Claudel, or Aristide Maillol with their portrait busts, mythological figures, nudes, and dancers. The avant-garde drew on a whole new visual vocabulary in which mass culture and industrial production as well as dreamlife and the unconscious were in play. Much more can be and has been said of course about all of this and nothing I am saying here is news. But I am putting this brief introduction in place to frame the challenge of reading Meret Oppenheim’s poems by contrast to the immediate legibility that for me inheres in her sculptural works. How interesting is it to contemplate that challenge? How is it that contrasting degrees of legibility are so present across art forms?

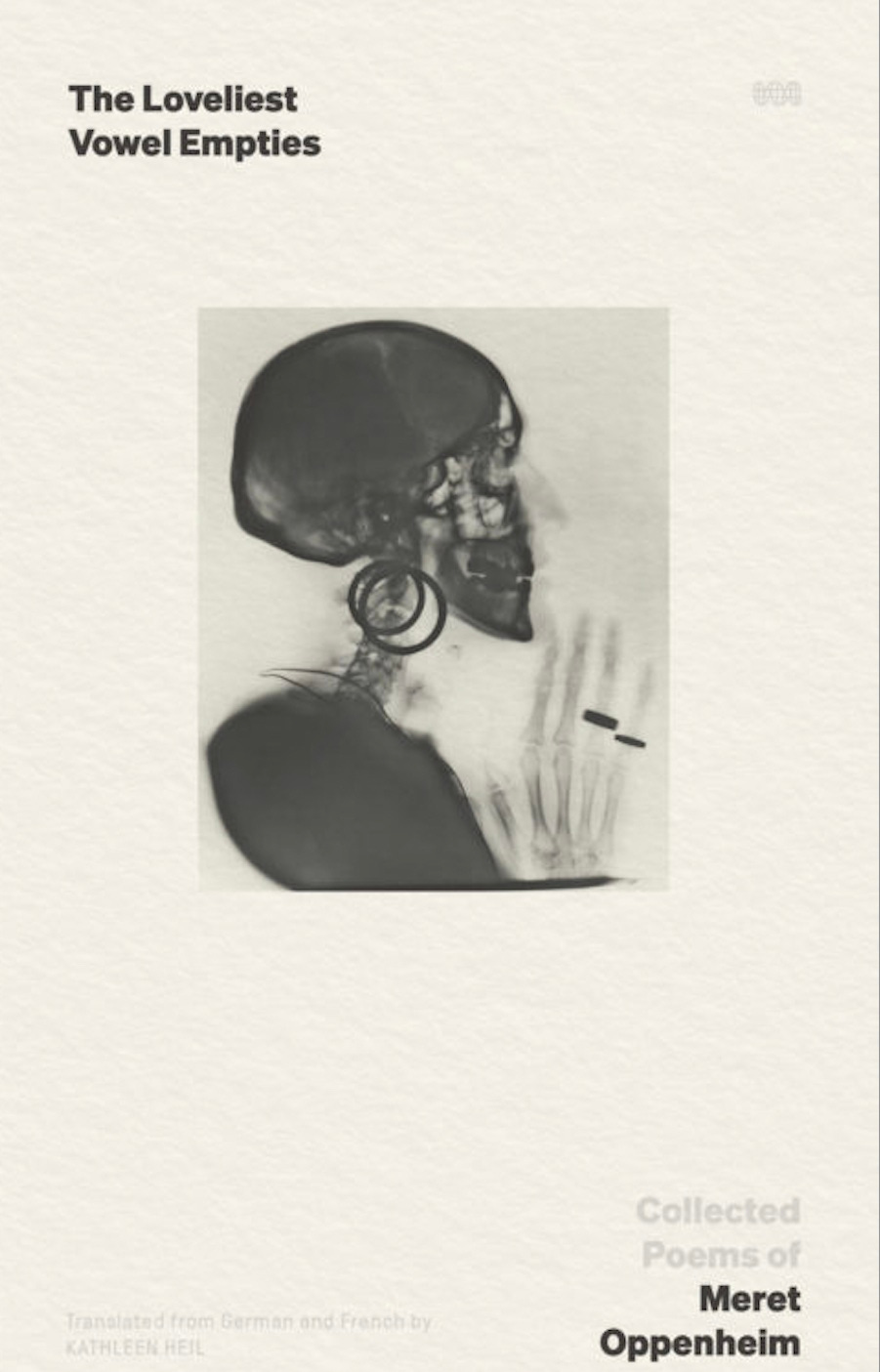

The recently published Collected Poems of Meret Oppenheim, whose title, The Loveliest Vowel Empties is a line from one of the works, is part of the ongoing activity of the World Poetry publisher. Their elegant editions present significant translations of works that are not otherwise available in English. Finely designed and printed on soft warm paper, the volume of Oppenheim’s poems was translated by Kathleen Heil, a poet whose own profile includes dance and performance as well as literary activity. I do not read German well enough to gauge the translation. But I trust Mary Ann Caws’s comments on this aspect of the work. Caws makes the point that Heil choses many words that others might find “out of the way” as part of reinforcing the disorienting surreal quality of the language. Her choice of vocabulary likely reinforces qualities that are part of the original texts. My difficulty in reading has nothing to do with Heil, but with my own linguistic limitations. My response is based on the English words and syntax, but the alienation I feel is not a criticism of either the original or the newly published version. Quite the contrary. What interests me is why I am so ill-equipped to read the poems when I can “read” Oppenheim’s sculptures into and out of the many threads and nuances of reference through which they obtain their resonance.

Two factors contribute to the difficulty of my reading experience. The first is that I am simply not as literate in poetics as in visual art. By training and disposition, I find visual art more apparent. Not that it is immediate—unmediated, simply there—not at all. But the visual properties are mapped in my perception to historical and cultural conventions whose familiarity runs deep, as per the perfunctory intro notes above, I can read the fur cup through its production to its conception along a trail of associations and references, historical specificity and contextual origins. But the poems? I have a sense of them, of the crucible from which they spring. I can hear the legacy of Symbolism, the noise and vernacular of Modernism, the vividness of Imagism, the transformative shifts of Surrealism, surprise of the Dada compositional mode. All are present. I could point to instances of each with some measure of reliable judgment as I go through the works. But my knowledge is superficial.

The second factor is that the works seem disconnect from their lineages, which is to say, those textually specific elements are not a whole story. Darkness reigns in these texts. The lack of optimism, bordering on despair but with a twist that feels cultural and gendered rather than personal, seems to suggest they be read in relation to events unfolding at multiple scales in Oppenheim’s world. Heil comments on this in her useful introduction, wondering “if it isn’t possible to shift the personal to the social”–which included both the male-dominated milieu of 1930s Paris art circles (hang out with André Breton, Man Ray, Max Ernst and the occasional Marcel Duchamp anyone?) and the “reality of violence and war” in the same decades. Born in 1913, Oppenheim was of German-Jewish and Swiss ancestry and the events of the 1930s and 1940s were registered in the tone and imagery of these poem texts. But to generalize about such events and presume to interpret the works of an individual in relation to such broadly stroked frames is as disrespectful as ignoring their role.

What do I read these poems against? In relation to? How is their specific identity apparent to me—or, as I keep suggesting, not legible. My ineptitude combined with the poems’ specific qualities leaves me with the problem of “simply reading” them without being able to situate them in any larger poetic context, or assigning dubious attributions to some of their properties. For instance, some odd antiquarian terms and images persist—the coach, the goddess, helmets, carriage and cart, the king with “golden plaits” and “ringlets” or “silver dew” and “pearly globules”. Is this symbolist fantasy language, still circulating? Or the residual of her upbringing and education? Flowers, animals, and insects are omnipresent along with the lions, dogs, ravens, butterflies and daffodils. Absent are the buzz and noise of machines, the haste of modern life, the stench of smoke or thrill of speed. But what is going on outside the window of the room in which she is composing? Where is she in place and time, her own life and that of others? And what choices was she making about what the language was that was available to her? That is the final question on which I land in trying to understand my inability to read the work adequately. How do I know? Again, in terms of imagery and material production, I can answer that question if speaking of the sculptures. I cannot do that with the poems because I do not feel sufficiently familiar with the language context to fully read the work.

In the end, reading and re-reading, I see the individual identity, the quality and character of voice and tone, the shape of thought transforming into language that is itself often enacting dynamic change, metamorphosing from one state to another through imagery remade by action verbs that rapidly alter the outcome of a syntactic trajectory. The title phrase is one striking example, “The loveliest vowel empties” (19) but in the short poem it follows two other lines to complete the text: “We feed on berries / We worship with the shoe” (19). Compressed and succinct, the poem necessarily returns us to Rimbaud’s Voyelles, a singular reference that cannot be ignored. No poet can invoke “vowels” without the ghost of Rimbaud falling on the page. But the use of verbs as a pivotal element in image production is everywhere: “At regular intervals the trains are drawn from / Their barrels emitting torrents of water […]” (41) or “Nevertheless they matter, too, the forgotten nightingales / eating granitic soup and biding their time.” (93). The verbs change the trajectory of the image mid-sentence.

The feminine features of subjectivity evidence themselves in the nuanced lines, the selections of vocabulary, multiple images of female figures but also a constant location of perception in somatic references. The final poem for instance, “Self-Portrait from 50,000 B.C. to X,” opens with a series of statements starting from bodily places, “My feet […]” “My belly […}” “In my hands I hold […]” (119) or earlier a poem treating a “Mother-of-pearl status” begins “Hot hand on the cool iron fence” (113). But also, the gestures of effacement, “You hide behind a moth / making its finest mimicry” (95) comes after questions and uncertainties, “Where is the carriage heading?” and a dismissal, “Here, no spirit of fellow feeling rules […]”. Potent, powerful, and direct as her writing is, she equivocates, hesitates, not doubting her perceptions, but expressing doubt as a condition of knowledge and awareness in and of the world.

Many compressed locutions articulate her perception on the thin line between abstraction and concrete impression. “Who thieves madness from the trees?” “[…] you cleave the scent from your journey.” (23) But here I am stopped by the language barrier, trusting the translator to have chosen just these words with their unusual tone and hint of earlier usage. Words like “fetch” or “mauve,” “asunder” or “unfurls,” also speak of another age and time before modern convenience or conveyance. I sense, but cannot fully read, the language, unable to locate it with certainty within the larger field of poetic and linguistic practices. Similarly, I don’t know how those compressions came into being, or when, even if I can feel their relation to the work of immediate contemporaries and predecessors in that cosmopolitan world of the historical avant-garde.

Appreciative of this volume, of the provocation it provided, and also, of the chance to see this other dimension to Oppenheim’s work. In another, unrelated by parallel vein, I became interested in the poetry of Florine Stettheimer when I was assigned the task of curating an exhibit of her work at Columbia University in the early 1990s. Not only was Stettheimer derided and disrespected in that period, but her poetry was beyond the beyond with its blatantly gendered eroticism and sugar-candy qualities. I loved it, and found its connection with her paintings to be most interesting for their flagrant and flamboyant embrace of femme tones and thematics. Oppenheim’s feminine identity is more aggressive, harder-edged, and she was also born fifty years later than Stettheimer. Oppenheim does not trouble herself with social activities or comment on them in sculptures or poems. The social is a much broader sphere in her work, encompassing a world of close and distant current events. Personal relations flit through the works, the “you” addressed seems to vary in degrees of intimacy, even number, while only sometimes hinting at singular transactions. The deliberateness of poetic composition—choices at every turn, carefully considered constructions—is apparent in these works. But how they are deliberate is what I am inadequately prepared to understand. My limited knowledge is the limit of legibility. I lack the specialized skill required to read a work in its historical as well as current context.

My one, small, suggestion for this volume would have been to include the dates or writing or first publication where known. At the risk of over-determining the reading in relation to those time-stamps, their inclusion would have provided one anchor for the reader, well, for this reader in any case.

World Poetry Books defines its mission as a commitment to publish “exceptional translations of poetry from a broad range of languages and traditions” thus making many works available for the first time in English. Publisher Peter Constantine and editor Matvei Yankelevich founded the organization in 2017 and have published more than two dozen works since that time. Among them, the wonderful typo-translation of Ardengo Soffici’s work, Simultaneities, on which I commented a few posts back. Theirs is an incredible and generous contribution to contemporary publishing.

To purchase The Loveliest Vowel Empties contact: https://www.worldpoetrybooks.com/product/the-loveliest-vowel-empties/

For more information on Oppenheim and her work:

Bravo.

Would it help if the translation had the original language printed on facing page?