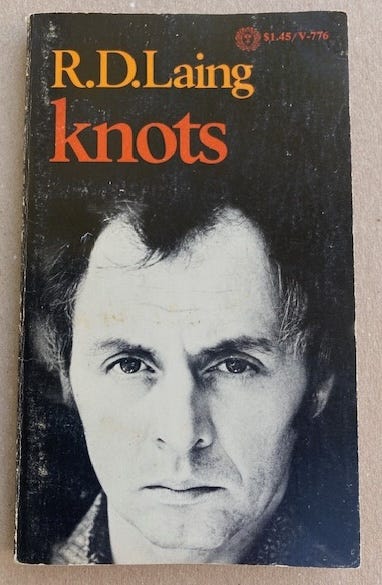

R.D. Laing, Knots, cover image, Vintage paperback.

This slim paperback surfaced recently in the bookstore at Beyond Baroque, a long-standing venue for literary activity in Los Angeles. The bookstore serves as a repository of deep history, with forgotten titles like this one found among other the recent publications stocked for readings and events. Some of these treasures evoke nostalgia, some curiosity, others, like this, are oddly compelling. For one thing, the black-and-white cover photograph of its author, the Scottish psychiatrist R(onald) D(avid) Laing (1927-1989) has a distinct intensity. The still-young man confronts us with an enigmatic, perhaps slightly sullen, expression that also could be read as a challenging invitation to a conversation. His eyes have the focused gaze of a mesmerist, his pale face and rather delicate features suggest an aesthetic cast to his character. But the poems in this book? That’s where the intrigue develops.

Laing was something of a hero in our counter-culture circles in the late 1960s and early 1970s for his then radical criticisms of conventional psychiatry and its brutal methods of treatment. Electroshock and other harsh treatments were being used on schizophrenics and other patients and the idea of treating behavioral issues with such crude physical methods seemed wrong to Laing. One of his insights was that the utterances of a schizophrenic were valid communication of their experience, not incoherent ravings. He advocated humane and compassionate treatment that was based on recognizing that non-normative behaviors were symptoms of suffering, not of pathological deviance

His 1960 book, The Divided Self, developed a popular following. Its subtitle, An Existential Study in Sanity and Madness, hinted at the combination of philosophical and medical knowledge on which it was based. The very idea that existentialism, the philosophical position that questions the meaning of existence in terms of absurdity and individual responsibility, would be part of a psychiatric practice was revolutionary at a moment when psychiatry was still struggling to establish a legitimacy within the medical profession. Interestingly, the book showed up on dorm room bookshelves and reading lists in my college years (early 1970s), though in retrospect I wonder how well the work was contextualized within broader debates. Anti-psychiatry, like anti-establishment rhetoric, was in keeping with the mood of the times. Peers who had been through treatment found its arguments crucial to their own recovery since it validated their sense of having been subjected to mistreatment rather than healing practices. For a more general readership, The Divided Self (with its elegant mid-century modern cover design of intersecting circles) put forth a description of the conflict that develops between the “authentic” true self that is mainly private and the persona we create to fit into the social world. This powerful concept worked well as a part of the broader interest in personal growth, self-help, and spiritual development that was prevalent in 1960s counter-culture.

But psychiatry was still a newish science in the mid-20th century, and considerable stigma attached to the diagnosis and treatment of any behavior characterized as “mental illness.” Sam Fuller’s 1963 film, Shock Corridor, Ken Kesey’s 1962 novel, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, or Susan Kaysen’s personal memoir, Girl, Interrupted, about her experience in a psychiatric hospital in the 1960s are all graphic testimonials to the public perceptions of the field at the time The Divided Self appeared. Laing’s commitment to engaging compassionately with his patients went a long way towards changing that perception. Still, in my family’s circles in the late 1950s and 1960s, mention of psychiatrist treatment took place in very hushed tones as something to be kept very private even in intimate communication.

I have no idea how Laing’s positions are currently viewed within the psychiatric profession. As he separated from the training he had received he became associated with the “anti-psychiatry” movement. Convinced that schizophrenia was the outcome of trauma, particularly within the family, he even suggested that it could be compared to a “shamanic” journey of discovery, a position that was problematic to many but resonated with counter-culture sensibilities. He rejected various fringe approaches, but did become involved in the “re-birthing” movement that fostered exactly the process its name suggests—allowing individuals to re-enact and/or re-experience the trauma of the birth canal. All of this may sound wacky and early new-age-ish, but in the 1970s I knew various people involved in these activities, some of whom benefitted from the experience. These connections established Laing’s reputation within venues like Esalen where he was seen as progressive and enlightened.

These were the visible and familiar aspects of Laing’s profile. His identity as a poet was not. Published in 1970s, Knots was never among the canonical references to his oeuvre, nor was it part of the corpus of poetry texts “everyone” read in that decade when Gary Snyder’s Earth House Hold (1969), Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s Coney Island of the Mind (1958), Ginsberg’s Howl (1958), or the very trendy Richard Brautigan’s Trout Fishing in America (1967) were circulating widely among my peers. We also read the Beats, some classic Anglo-American poets like T.S. Eliot, writings by Emily Dickinson, or Langston Hughes. No one brought up Laing as a poet.

Knots is an oddity. The texts read like logical analyses and are focused on behaviors, particularly the interaction between two characters, Jack and Jill who are wrestling with miscommunication and desires at cross purposes. These characters are not introduced until the very last page of section 1 of the book in a formulation that is quite typical of the texts throughout:

it hurts Jack

to think

that Jill thinks he is hurting her

by (him) being hurt

to think

that she thinks he is hurting her

by making her feel guilty

at hurting him

by (her) thinking

that he is hurting her

by (his) being hurt

to think

that she thinks he is hurting her

by the fact that

da capo sine fine

This structure of refracted exchange persists throughout the verses, with parent and child, lovers and others, always engaged in a dynamic asymmetry of understanding. The hide-and-seek game of attention to another, of trying to grasp an interior state, apprehend motivations, perceive another within the paradoxes of intersecting subjectivities is played out on every page. In the review of the book that appeared in the New York Times upon its publication, the writer James S. Gordon said this: “The knots are ‘patterns…of human bondage,’ descriptions of the bonds (or binds) that people–parents and children, lovers, friends, therapists and patients–put each other and themselves in.”[1] Gordon goes on to say that the work is “meticulously constructed, often hilariously and painfully recognizable.” Gordon was using the book in his own psychiatric practice, having patients read the texts aloud and work them through. He cites the first poem in the book, which is just four lines:

They are playing a game. They are playing at not

playing a game. If I show them I see they are, I

shall break the rules and they will’ punish me.

I must play their game, of not seeing I see the game.

As poetic work, Knots has an inexorable logic to it, an insistence on an analytic rather than subjective approach to human experience even as it constantly identifies the subject positions in the texts. One of its more unusual aspects is that it contains various diagrams that schematize the relations being presented. Arrows and graphical structures position the verbal components in some of the poems while brackets, numbering systems, and other devices encode the writing in a formal structure.

Diagrammatic structure in Laing’s poetic text.

As I became aware of experimental writing closer to my generation, formalisms and procedural logics did not make an immediate appearance. The computationally-driven work being done in Stuttgart, Ulm, and a handful of other environments in the 1950s and 1960s had not circulated into my networks in the Bay Area. Even the visual poetry of the Noigandres group in Germany and Brazil had not quite come to our attention, so the only graphical scoring I was familiar with had been in the works of American poet, e.e. cummings–and he is far from being a procedural writer. Laing’s innovations register all the more, their originality and intellectual rigor remarkable within poetic production. Encountering it now, half a century later, I find the distinctive contours of its intellectual approach striking, its analytic formalism unusual.

On the Wiki profile page dedicated to Laing, he is shown perusing a 1944 publication, the Ashley Book of Knots, a volume that is regarded as the gold standard for tying string or rope into specific configurations.[2] Taken in 1983, the image shows him in rapt concentration, a bemused expression on his face that suggests his absorption is clearly motivated by more than casual interest. That work, which contains about 7000 drawings of more than 3800 different knots must have provided considerable satisfaction to Laing, given his fascination with the variations in the ways interactions among human beings took shape.[3] This is supported by Laing’s suggestive prefatory note in Knots, “The patterns delineated here have not yet been classified by a Linneaus of human bondage.” Whether Laing had in mind to take on that task is unclear, but that he at the very least laid a conceptual foundation for it is evident.

Knots is not your average book of verse.

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/1970/12/13/archives/knots-the-bonds-and-binds-that-others-put-us-in.html

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/R._D._Laing

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Ashley_Book_of_Knots

Thanks very much for this.