Poetics of (Re)Cognition

Jessica Lewis Luck, Poetics of Cognition: Thinking Through Experimental Poems (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2023)

and

The Collected Poems of Donald J. Trump (Los Angeles: Privately printed, 2024)

Many claims have been made for the political efficacy of the avant-garde. From the earliest manifestos of early twentieth century movements like Dada, Surrealism, and Constructivism, through to the present, a persistent tenet of belief has been that the disruption of normative syntax, invention of radically innovative forms, and other aesthetic techniques for the subversion of expectations in readers, viewers, or listeners has a political impact. Though largely dismissed by more recent critics and literary historians, for whom the conspicuous absence of evidence of such effects is apparent, the belief continues to have its adherents. The academic industries of art history and literary criticism (and their counterparts in practice) have been built on this position, with mid-century Frankfurt School figures like Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer as major touchstones for theoretical justification. While I have my issues with the to-my-mind exaggerated claims for a link between difficult work and direct political effect, I remain convinced that experimental art (literature, film, music, performance, visual work and so on) has a cognitive function that is significant. Some good reasons for this can be found in the alternative—the production of formulaic artistic objects that are part of the standard culture industry—the pablum bland productions that pander to middle-brow mindless consumption and distraction creating a persistent dull adherence to the status quo.

Jessica Lewis Luck: https://uipress.uiowa.edu/books/poetics-cognition

In her recent critical study, The Poetics of Cognition, Jessica Lewis Luck takes up these issues in a refreshingly different argument that draws on theories of cognition from a neuroscience perspective. Luck opens by sketching the legacy of the just-noted critical position in her introduction. Luck cites Rita Felski, The Uses of Literature, saying the critic is “is skeptical of the avant-garde’s utopian linking of aesthetics and politics, of the notion that shocking works of art could somehow ‘topple banks and bureaucracies, museums and markets.’” (9) The discussion of these positions could and has spread to volume after volume of critical writing, with the persistent myth and theory death of the avant-garde as their focus. But having established the background, Luck goes on to her own interesting work which, as already noted, makes use of a very different foundation in cognitive psychology.

Luck’s major argument is that the defamiliarizing experience of encountering experimental work is cognitively generative, that it produces new knowledge and new modes of processing. This make sense intuitively as well as being able to be tested experimentally, and though Luck is not a clinician, she makes use of research by, for instance, Travis Proulx and Steven J. Heine who published their findings in Psychological Science. Proulx and Heine are just one example among the many researchers on whom Luck draws to frame her argument. Luck terms the “cognitive materialist approach” (14) a “biodiscourse” in which strangeness “can reinvent or rewire the embodied mind” to some degree in a psycho-physio-material way. In the field of cognitive poetics, Luck finds support in the work of Reuven Tsur, Mark Turner, and Peter Stockwell among others, and makes a convincing argument about neuroaesthetics (drawing also on the high-profile writing of G. Gabrielle Starr). In the work of poet and neuroscientist Jan Lauwereyns, Luck finds particularly strong support for the capacity of experimental poetry “to transform the very cognition from which human experience emerges.” (16). This is solid stuff and Luck uses it deftly in her arguments.

The chapters in which Luck develops her discussion focus on various poets and poetic practices. She begins with the late Lyn Hejinian’s My Life, an autobiographical prose-poem (Burning Deck, 1980). The second chapter focuses on Harryette Mullen’s Sleeping with the Dictionary (2002), the third on Larry Eigner’s “projected verse,” and the fourth and fifth are on a selection of visual and sound poems, many classics in their field. While keeping her line of argument in view, she also stresses the embodied aspects of cognition, both in the writing and the reception of the works she examines. Her readings are crisp and sharp, and some of her ancedotes, such as the response of the House of Representatives to Aram Saroyan’s receipt of a $500 fee for a visual poem that consisted entirely of the single neologism, “lighght,” are gems of culture war history. Her account of the bafflement of the lawmakers is sufficient to make the case that defamiliarization does indeed have an impact, though Luck goes on to use the poem for a more informed discussion about the distinctions between phonological and lexical readings, not just as an example of how far apart the tastes and understanding of elected officials and experimental poets might be. (97)

For those familiar with the experimental tradition in late modern and postmodern poetry, the choices are perhaps too obvious and the selection has a bit of a “check the demographic boxes” feel to it, but after all, most readers are not playing insider baseball here. Luck chose works that could connect with readers for whom the materials are new. By picking difficult works that have recognizable thematics–autobiography, the dictionary, typing/writing, and other topics– she gives new readers something relatable as a start point. Luck’s readings of the works contain many well-formulated insights about wor(l)d-changing practices seen through the lens of her readings in cognitive science.

Luck’s hypothesis, that “experimental techniques can generate new practices of thought” may need to be proved with empirical or observational results. But she argues suggestively and convincingly, and hers is a position to which I am sympathetic. I have never believed in the direct claims for political impact of obscure, difficult, resistant work, but the possibility that the effects of exposure to novel ideas and innovative work produce an experience that affects neuroplastic aspects of cognition seems fully credible. Language that pushes back, calls to attention, offers an alternative to the varieties of mind-numbing experience may not be sufficient as an instrument of transformation, but without it nothing changes.[1] The point of aesthetics, conceived as that aspect of philosophy concerned with perception, is to engage with the question of how we have experience, not just what experience we have. I have spent most of my adult life in these worlds, and am familiar with (and skeptical about) the claims of the “political” work of poetry. Luck’s smart decision to shift to the cognitive realm is most welcome and her book makes a unique and timely contribution with a convincing argument.

Re-Cognition: The Collected Poems of Donald J. Trump

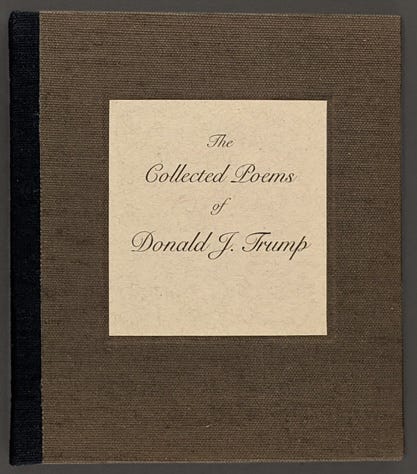

To the unsuspecting reader, the appearance of this well-made volume suggests a precious gift-book, a novelty item, fitting easily into the hand, its book-cloth cover and inlaid label promising a material experience of equal richness. The elegant black cloth spine and dark green-grey textured fabric cover open readily and the book block is revealed, its earth-toned end sheet echoing the rich colors of the binding. An elegant thing indeed.

The Collected Poems of Donald J. Trump, 2024 (Photo courtesy of Levi Sherman).

Like many successful artists’ books, this one, made by Brad Freeman, causes cognitive disturbance as the anticipation of experience gives rise to bafflement. The promise of entering the book, moving from outside to interior, is quickly subverted as the reader/viewer turns to the first page. There, the stark presentation of the page number is all there is to see. Turn the page, and again, the sheets are blank except for another page number. Turn again. By the time the “reader” arrives at the third opening, it is clear that nothing else is going to appear. The “collected poems” are just that—absences, blanks, nothing at all. If Luck’s work dealt with the capacities of experimental writing to rewire cognition from a deliberately constructed poetic practice, this book demonstrates the equally potent capacity of artists’ books to provoke surprise with the question: “What??”

I have watched numerous persons encounter this volume of The Collected Poems and all have the same response. Their initial perplexed disbelief at seeing the cover and the object is confirmed by the surprise of the interior. The statement the work makes is devastating in its deadly skewering of un-cognition, the complete lack of aesthetic awareness and sensibility on the part of the figure whose bludgeoning anti-intellectual campaigns against all forms of knowledge would, of course, eliminate poetry as a reality from his realm–if it ever existed there.

Several smart critical responses to this work have already appeared. Book artist Clifton Meador, in a privately communicated review, wrote the following:

“This anthology, curated with a mix of humor and seriousness, showcases Trump’s unique voice and perspective through a series of poems that range from the absurdly grandiose to the introspectively simple.”

“The poems reflect Trump's trademark bombast, with vivid imagery and a distinctive cadence that is unmistakably his. From odes to the American Dream to verses that poke fun at political rivals, the collection is a testament to his flair for the theatrical. While some may argue about the literary merits, the work undoubtedly captures the essence of a figure who has redefined modern political discourse.”

Meador goes on to comment on the typography and layout and their work in support of the writing.

Artist and critic Levi Sherman, on his Artists’ Books Reviews site (https://artistsbookreviews.com/), opened his discussion with a description of the book: “The title is set in a script typeface that looks elegant the way Mar-a-Lago looks elegant. […] Its slim proportions do hint at a dearth of poetry; inside the clothbound hard covers is a single sewn pamphlet.”

Commenting further on the design, Sherman says, “The page numbers focus the reader’s eye as they thumb through the stark white pages. They also mark the passage of time and — at the risk of projecting onto the book’s blankness — remind the reader of its finitude. Trump’s presidency will come to an end.”

Sherman reads the material features of the book object clearly, seeing its significance in the idea that “[…] Freeman silences one of the world’s most powerful people. Taken as critiques of authoritarian politics and cynical profiteering, these blank books demonstrate the difference between being speechless and having nothing to say.”

The eloquence of the artifact is performative, the material message is clear, but it is the element of surprise that really does the work of transforming expectations into critical insight. In that gap, between encounter and subversion, cognition occurs. Here we see Luck’s arguments demonstrated vividly in the generative activity of (re)cognition.

Thanks to both Clifton Meador and Levi Sherman for permission to quote from their work.

n.b. The colophon for The Collected Poems reads Concept, editing & production are by Brad Freeman. Body type is Harriet by Okay Type Foundry, Chicago. jabandbrad@gmail.com

journalofartistsbooks.net Mar Vista, CA 2024

[1] Those interested in the historical frameworks for these debates could revisit the volume, Aesthetics and Politics, a collection of essays that includes foundational work by Theodor Adorno, Walter Benjamin, Ernst Bloch, Bertolt Brecht and Georg Lukacs. Initially publishing in 1977, it is a collection of essays by the leading figures of the group known as the Frankfurt School, German philosophers whose writings in the 1930s to 1950s provided the basis for much of the intellectual tradition of the avant-garde in Europe and North America. See Google books: https://www.google.com/books/edition/Aesthetics_and_Politics/rov-DwAAQBAJ?hl=en