Performance on Paper

Works from the 1960s to the Present. Hammer Museum, Los Angeles. May 3 to August 10, 2025

Jason Moran images, Performance on Paper, installation view. Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, May 3–August 10, 2025. Photo: Jeff McLane.

For more images in the exhibition, see: https://hammer.ucla.edu/exhibitions/2025/performance-paper

Walking into the current Performance on Paper exhibit in the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, the first thing that grabs your eye is a line of four dramatically dynamic works by Jason Moran. Made with cyan powder transferred from the impact of the artist’s hands as he played a keyboard with fingers dipped in the bright blue pigment, they communicate the energy of active touch. Striking in their own right, they embody the central theme of the exhibit. This is clearly performance on paper. The sound waves, body language, mood, tone, and presence of the performer have all vanished. All that remains are the traces of his hands, but they communicate the vigorous action that occurred at a particular place and time.

Every drawing on paper might be considered a performance. Some are also performative—making something happen as with an “X” signature or a line encircling objects to make a grouping. We could quibble over whether marks made by hand and those made by a machine are equivalent, but all marks are traces of action of some kind, even at their most minimal or mechanical. The pieces in this exhibit each have a direct relation to performance events and are linked to the often ephemeral activities of experimental art and music communities of the last half century or so. Ever since John Cage had his now legendary classes at the New School in New York City between 1956 and 1961 and also participated, albeit intermittently, with the equally legendary activities at Black Mountain College in Asheville, North Carolina, beginning a decade earlier, the idea of alternative scores has been part of the vocabulary of innovative artists (dancers, musicians, writers, and other performers). Some earlier precedents for non-conventional performance scripts exist, as examples in Notations, jointly edited by Cage and Alison Knowles demonstrates in a handful of selections from the years leading up to its 1969 publication. Cage is represented in the Performance on Paper exhibit, and his own scores could sustain interest across many galleries. But beyond his significant impact, the variety in these works shows how heterogeneous performance practices have become in creating scripts.

In demonstration of this point, the graphical work in this exhibit is not limited to scores. In fact, a schematic typology of the works on display would include some interesting categories: direct traces of performances created by actions of a performer or instrument, scores in a variety of notation systems (many invented), documents of performances in the form of texts, correspondence, photography or collage, translations of a performance into a graphic by way of analogy and remediation into a different medium or language, and finally, performance instructions scripted on the page. Vivid works appear in each category, but at a critical level, they allow for reflection on the multiplicity of forms of notation. These classifications are not the standard categories of visual art, and so it is interesting to think about the ways this exhibit calls the distinction between systematic code and inscription into focus differently from traditional painting and drawing.

Rudolf Laban’s scheme for encoding movement, in Schrifttanz, 1928, an earlier system for encoding dance.

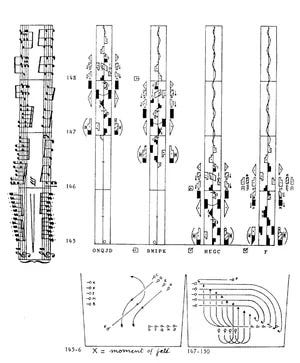

Code is structured, a form of putting information into a regular rule-bound system of records that can be read, repurposed, used across time. For example, the notational quality of the elaborate work by Channa Horowitz, Sonakitography (2012), made with plaka on mylar in an elaborate chart is a large, obsessively replete, work that executes its code in grids of color annotations whose values are fully formalized. Other elegantly imaginative notational systems here include Charles Gaines’s transformations of photographs of Trisha Brown dancing with a partner. The dancers’ movements and shadows are translated into a set of number codes that make their own (not always imitative) patterns. These can be looked at without having to be read, though engaging with the process adds to understanding. Another work consists of a portfolio series of choreographers’ works commissioned by Kristy Edwards when she was heading UCLA’s CAP (Center for the Art of Performance) series. This portfolio shows how wide-ranging are current ways of thinking about translating dance and movement into symbols, ideograms, and diagrammatic schemes. One of these, Alice Sheppard’s relief-printed tactical graphic makes a bridge between its physical format and instructions for physical activity. These code works could be further classified by whether they are iconic (showing poses), dynamic (showing movement), or instructive (offering a script for action).

The intellectual systematicity of notation expresses deliberate analytic labor, development of a code through which to translate performance for production and preservation. Codes require a key for their use, a way for their sometimes esoteric systems to be read, whether by a human or a mechanical device. Allen Ruppersberg’s Great Speckled Bird, reproduces correspondence written on now-vanished hotel letterhead stationery. The long continuous print on perforated piano roll paper references the loom cards that were precedents for the early computer punch cards. These imaginative technological tools have a long history with aspects of place-value calculators linked to the abacus, the wonderful Pascaline invented by Blaise Pascal in about 1642 (he was nineteen), and designs for Charles Babbage’s never-fully-operational Analytical Engine envisioned in the early 19th century. Perforations are physical codes that produce direct action, but other codes can be subject to considerably more interpretative range.

The direct inscription, or making of a trace of movement, like Moran’s cyan works mentioned above, is not necessarily “informational” in the way as notational codes. The “drawing” made by Tom Marioni’s drum brushes as they are scraped by sandpaper to leave a trace is expressive, alluring, and elegant, but it doesn’t strictly encode information. From a forensic point of view, one could dispute this, perhaps, and find somatic patterns that would link a musician to the trace of their playing, but that is a bit of a stretch. Other works in this vein include Trisha Brown’s footprints and Julia Phillips’s Dance Marks from 2014 that hark back to various Happenings and conceptual pieces beginning the 1960s by Yves Klein, Yoko Ono, and others who used their bodies to create works.

In moving across modalities from performance to graphic media, certain principles of translation come into play. In one example, Vera Molnár’s graphic geometrical drawings on an accordion-folded paper strip were used by the composer Jean Yves Bosseur to create a musical score whose notes were placed according to the shapes in the artist’s drawings. Cleverly titled, Ni queue ni tête (Neither tail nor head), the work is printed on both sides of the sheet in a way that makes it impossible to see them simultaneously. Not all signs of traditional composition are banished. Meredith Monk’s elegant Vocal Gestures use conventional musical staffs for reference, but like Raven Chacon’s scores placed nearby, employ an engaging visual vocabulary. Chacon’s pieces are each distinct, with diagrammatic symbols that are linked to his Diné Native American tradition. The two artists’ works dialogue with each other, raising questions of how symbols might be interpreted across cultures as well as time.

Almost every work in this exhibit could sustain a critical discussion about performance as well as visual systems. Among the works that are documents of events, Laurie Anderson’s record of “BUY BUY WRITE” from a 1976 performance has a wry authenticity to it that reminds us of that artist’s feisty irreverence and feminist attitudes in an earlier (combative) era. Kandis Williams’s documentary collages, Black Box, are among the few works that use photographs of bodies in gestures of expressive motion that combine representational imagery and graphic collage form.

While not every piece in the exhibit worked for this viewer, the exhibit was impressive for its curatorial deliberateness and care and the way the selection of works presented a point of view about these crossovers. The focus was reinforced by the installation, the professionalism of which cannot be taken for granted in these days, even in museum settings. Replete but spacious, the groupings and spacing of the works gave each a discrete identity even as they contributed to the larger argument of the exhibit—that these are performances as well as being documents and records.

Among these records, Shadows Evade the Sun (2012) by Dario Robleto evoked a strong emotional pang. Robleto’s color photographs of stage lighting at individual performances in the last half-century are arranged in a grid of nine images. No people are present, only these haloes and lens flares, glows and auras, captured at concerts given by members of the musical pantheon: Johnny Cash, Dizzy Gillespie, Sam Cooke, Ella Fitzgerald and five others. The luminous traces reach us like light from distant stars, playing with the notion of stellar brightness. Each has a distinct tone and mood, a sense of the vanished moment, fading from view even as it is captured on film. The poignancy of these records, a purple ground for Cooke, a blue-green blur for Charlie Parker, registers with the resonance of disappearing notes. Now these are images from the past, time travelling, and the final image in the set is a four-armed blaze of blue-white light against a deep blue ground taken at an Elvis Presley concert.

Interesting to think about these works in relation to larger historical traditions and the way writing and record-keeping emerge and become conventionalized. For instance, the ancient notational codes of Sona and Tusona markings created by women in Zambia about two thousand years ago has pulled the contrast between “writing” and “notation” into international discussion just recently.[1] These systems of lines and dots, many correlated with observations of natural cycles and phenomena, were often used to make sand drawings as well as inscriptions on more permanent materials like wood or leather. Making records of events in coded form is at least as old as CroMagnon culture, some 40,000 years ago, in the marking of what may be lunar cycles or other events in tallies made on cave walls.

Writing communicates and encodes language, but many events and activities are not primarily linguistic in nature. Dance, music, movement of all kinds, the intangible aspects of cultural heritage, are only preserved if the ephemeral activity is recorded in some way. In these moments when disturbing events are unfolding, attention to aesthetic activities can be seen as a distraction–or a necessity. As we know, art will not save us from authoritarianism or tyranny, but appreciating and preserving creative work is an essential symbol of the humanity and value of imaginative work.

[1]Penny Dale, “An ancient writing system confounding myths about Africa.” BBC, June 7, 2025. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c5ye50xgw8vo