PATAQUERICAL BALLAD

Charles Bernstein and Runa Bandyopadhyay (Joyjit Makhopadhayay: Kolkata, 2024).

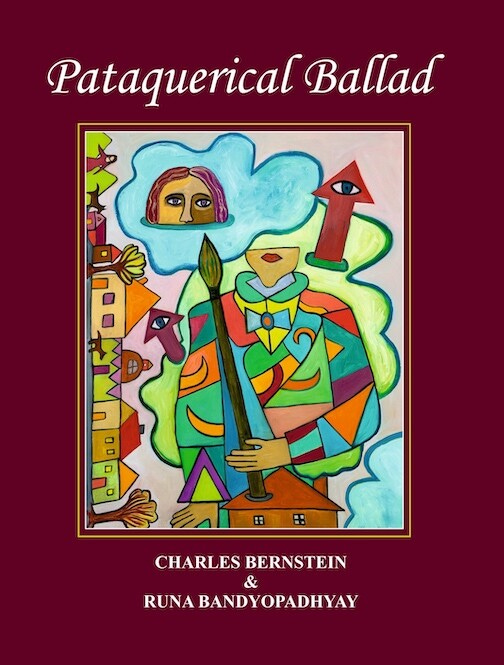

Charles Bernstein and Runa Bandyopadhyay, Pataquerical Ballad, 2024, Cover

Most significant figures in literature or culture are sui generis. No one confuses Ovid with Catullus, Petrarch with Byron, or Emily Dickinson with anyone else. But some figures are so unique their influence has the resonance of a radioactive isotope. Marcel Duchamp, for instance, changed the course of art and continues to be a force within conceptual work across genres more than a century after his outrageous 1917 display of a urinal, titled Fountain and creation of other works whose aesthetic impact seeps across time, space, and genres.

Among these singular talents, the late-19th-century writer Alfred Jarry stands out for making the concept of uniqueness a principle at the core of his philosophy of ‘pataphysics, which he defined as “the science of exceptions,” a concept he embodied in his life and work. Alternatively described as the science of imaginary solutions, Jarry’s work supports outliers, rather than outlaws, though his most famous work, the drama Ubu Roi (King Ubu), was a deliberate bad-boy slap-in-the-face farce whose vulgar humor was meant to shock the bourgeoisie in a now-classic avant-garde gesture. First performed in 1896, the play opens with the central figure uttering the French word “Merde!” with full scatological enthusiasm.

But Jarry’s ‘pataphysics goes beyond the adolescent attitude of Ubu through its focus on this “science of exceptions.” The relation between this formulation and the emerging codification of statistical methods in the late 19th century is worth more than a passing note—especially as the standards of analysis pressed into government, business, and sociological assessments so clearly aligned official administrative culture with these methods. Quantitative analysis, with its means, median, and averages, subsumed individuals under patterns, a technique that continues with full pernicious implications to this day. These issues are relevant to discussing the Pataquerical Ballad for a number of reasons, not least of is the through-line of both authors’ arguments against normativity and its dulling—even chilling—effects. Normativity takes many forms, and as poet-critic Charles Bernstein points out, appears in the realm of poetics as Official Verse Culture. For Bernstein (and many others, appreciative of his articulation of the issue), this institutionalized phenomena is nemesis of thought, imagination, even freedom of mind and creative spirit.

That the spirit of Jarry infuses this book from its adoptively morphed title to the textual play within is hardly a surprise for those familiar with Bernstein’s work. Irreverence, humor, the games of language that reveal unexpected connections and diversions that were part of Jarry’s writing continue to provoke intelligent textual experience. What is a surprise is the creative dialogue produced by Indian poet and philosopher Runa Bandyopadhyay across the cultural traditions that would appear to separate Vedic and Hindu thought from that of modern and contemporary experimental poetics.

Bernstein’s essay “The Paraquerical Imagination: Midrashic Antinomianism and the Promise of Bent Studies (A Fantasy in 140 Fits)” is the substrate here, the ground from which Bandyopadhyay’s discussion emerges in a highly structured commentary. For those unfamiliar with Bernstein’s extensive corpus, both essays offers a vivid introduction to his critical perspective. However, Bernstein’s career spans five decades and includes such now-canonical works as Content’s Dream (Sun and Moon, 1986), A Poetics (Harvard: 1992) including “Artifice of Absorption,” and the incomparable title essay in Attack of the Difficult Poems (University of Chicago, 2011).[1] Bandyopadhyay builds on the various artifices that structure Bernstein’s text—the identification of dramatis personae in a series of “Acts” interspersed with “Anecdotes” and, in the case of Bernstein, his characteristically condensed and aphoristic witticisms. Bandyopadhyay eschews standard criticism and her artful play weaves thematic skeins and threads of thought around the topical complexities and rich reference fields of Bernstein’s work.

Bandyopadhyay states her project clearly: discerning the conceptual map where Western and Eastern philosophies intersect. Her discussion is not a translation of concepts from one domain to another, but a work through which the connections are exposed as parallel lines of thought that intersect, complement, and extend each other. She fulfills that promise in a series of episodes (“20 Acts,” plus a “Preface” and final “Act Zero”) that connect concepts from Vedic and Hindu thought with the principles of the ‘pataquerical work within what Bernstein calls “bent studies”. Her preface is rich with suggestive phrases about the “imaginations of our intellectual wealth” and “the quantum coherence between the voices, processes, and thoughts of different poets, philosophers and scientists of the East and the West.” (10) The mash-up of poetic-theoretical discourse and scientific vocabulary makes evident the leaps that derive their inspiration from Alfred Jarry and Edgar Allen Poe, both of whom happily appropriated such concepts into their aesthetics. Though Bandyopadhyay’s contribution leads the way, placed first in the publication, it has to be read in parallel with Bernstein’s text, since that is its inspiration.

In Bernstein’s stand-alone essay, originally completed in 2015 after several iterations, and then published in The Pitch of Poetry (Chicago: 2016), puns and neologisms abound. Part strategy of linguistic deformance and part poetic play, these twists of sense perform various moves—they pivot, double back, transform, and sometimes flip the meaning of the words in use. Some examples of this word play, typical of Bernstein’s work—even one of its signature features—might be his invented terms: animalady, anaesthetics, and the title term ‘pataquerical. Or this short burst: “I told my wife the water is too shallow. She said, wait til you get to know it better.” (97) We laugh, but the insight into the shaping function of language as it creates experience in its forms is the deeper lesson. The play of stylistics and stylish articulation is only one facet of Bernstein’s work, which is serious in its concern with the history and practice of poetics.

Bernstein’s point of view is evident from the figures he cites and whose positions chart his intellectual lineage from the modern period to the present. Emily Dickinson, Walt Whitman, Hart Crane, but also, importantly, the afore-mentioned Poe, provide crucial touchstones, each for various reasons within their own work, its influence, and changing critical reception. Attention to the details of Dickinson’s autographic manuscripts, tellingly called out by poet Susan Howe, prompts Bernstein’s investigation of the way the 19th-century poet may have shifted frames—from location to temporality—in her work. For Bernstein, this shift—identified in a scan of the handwritten text—suggests meaning is a matter of duration, “a serial process wrested from acts of reading and interpretation.” He takes this one step further, seeing in Dickinson an anticipation of structuralist difference as a foundation to the work of language. This up-close and reading exemplifies the attention to particularity invoked by Jarry’s “exceptions.”

Bernstein’s attention to language, to its material manifestations and its literal “stuff” brings a constant refrain from William Carlos Williams into the argument, tying it to the longer history of Poe’s “this is a poem–nothing more” which is an insistence on the fact of poetry in its instantiation. Ludwig Wittgenstein, not surprisingly, provides other philosophical reference frame. Wittgenstein has long served as the philosopher for “language poetry,” that late 20th century formation that also drew on Russian Formalism, linguistics, and critical theory to formulate its socio-political stance for poetics. Marcel Duchamp, the champion conceptualist, like Gertrude Stein and Wallace Stevens, provides other stable coordinates in the constellationary sky by which Bernstein steers his argument about the persistent value of the concept of “making strange” that arose from the writings of Victor Shklovsky and other poet-critics of the historical avant-garde.

Bernstein is too self-aware to give in to being a closet Romantic, and he is also well aware that the aspirations for aesthetic activity to subvert the normative order, so long associated with that tradition, have only pale presence in the larger ideological struggles. But on the home turf of poetics, within the territories where the ongoing battles over the value of literary work are fought, the stakes are real. For decades, his diatribes against what he calls OVC, “official verse culture,” have exposed the features of its belief system. These principles have served as the basis for attack by figures in its ranks on Bernstein and others aligned with experimental poetry, language writing, and conceptual work of various kinds. Among these are a handful named in the essay Walter Benn Michaels, Charles Simic, and also the late Helen Vendler, all of whom have consistently dismissed experimental work in highly pejorative terms (69).

For those unfamiliar with the lines on which such battles are drawn, they are summed up briefly in Bandyopadhyay’s essay as the judgement of “reactionary poet critics” who, baffled by the fact that the works of experimental writers are not “immediately intelligible” marks them out as “barbarian” “others”. For Bernstein and others committed to experimental practices, the conventional verse formats of academic writing programs are anathema to poetic imagination and even more importantly, to the project of belief in the liberating power of aesthetic imagination. “The prison house of official verse culture,” a phrase that borrows from critic Fredric Jameson’s title for his study of Russian formalist investigations of the ideological force of linguistic convention, The Prison-House of Language, states the case succinctly.[2]

But reducing Bernstein’s work or Bandyopadhyay’s commentary to an attack on convention misses the point of their individual work and the dialogue between them, which is to demonstrate as well as argue for imaginative interventions with and in language, poetics, and culture. The pleasure of this book is that it continually opens up the generative spaces of thought identified by a figure cited throughout by Bandyopadhyay, the 20th century Bengali poet, Rabindranath Tagore, who encourages the insight about the world and the self that “must be born anew every moment of its life.” (77)[3] This example is doing exactly what Bandyopadhyay set out to do, connecting concepts of Brahma (action) with Bernstein’s “bent studies” in its dedication to move “beyond the ‘experimental’ to the untried, necessary, newly forming, provisional inventive” (77). Bandyopadhyay never tries to force equivalents across significant cultural traditions and their boundaries, but to engage similarities and differences in a refractive criticism that provides insight.

Invoking Barin Ghosal, another 20th-century Bengali poet known for his commitment to alternative practices and experimental work, Bandyopadhyay cites his work on “Expansive Consciousness” to make a direct link to Bernstein’s pataquericalism.[4] Ghosal’s idea of the use of words in a poem is that they are evocative rather than descriptive, provoking rather than pointing at a referent, a “SPARK” in Ghosal’s terminology, or “Spontaneous Power Activated Resonance Kinetics” that produces a “sudden resonance in the mind.” Bernstein and Bandyopadhyay elaborate on the concept of the ‘pataquerics. Its multiple meanings include the “‘pataphysics” of Jarry (again, the science of exceptions), the “queer” (“strange, peculiar, eccentric and uncommon”), “inquiry” which includes a “rejection of closure” but also a commitment to “differentiate poetics from literary theory and philosophy”, and finally “poetics” as an “activity of making and doing to replace the practice of preconception” to open “the space of possibilities with simultaneous inclusiveness and openness.” (11-12).

The spirit of Jarry prevails throughout these entangled essays. The visionary writer spawned whole movements inspired by his concepts. In France, the Collège de ‘Pataphysique was founded in 1948 to pursue the direction suggested in Jarry’s works, particularly the prose text, Dr. Faustroll.[5] Figures as distinguished as the French philosopher Jean Baudrillard identified with its activities and with the intensification of engagement with “imaginary phenomena” that exist beyond the reach of metaphysics. By definition, the concepts associated with ‘pataphysics are open-ended even as the approach is focused on “the particular”—in opposition to classical science and its focus on that which can be generalized.

In his introduction to the English edition of Faustroll, scholar Roger Shattuck traces Jarry’s intellectual formation and impact within the context of French Symbolism, with its contrasting stars, Arthur Rimbaud of synaesthetic Vowels fame and Stéphane Mallarmé, the genius of constellationary work and the investigation of chance. But he also tracks Jarry’s significant interest in the developments in natural science, particularly physics, and the work of figures like William Crookes and James Clerk Maxwell, whose molecule-sorting demon was at the heart of theories of thermal dynamics and equilibrium. Not surprisingly, Jarry coined his own neologisms (in addition to the crucial term ‘pataphysics), among them “ethernity” to describe a realm of “unknown dimensions.”[6] Shattuck suggests, and rightly I believe, that Jarry’s insights were very close to those that would become central to the theories of uncertainty that are central to quantum theory, the early 20th century work of Werner Heisenberg and others, as they align with the Latin poet-philosopher Lucretius’s concept of the clinamen, or unpredictable swerve that produces specificity and/or particularity. Jarry, I believe, would have been amused and pleased to have the connections between his principles and those of other ancient traditions perceived as clearly and artfully as they are in Bernstein’s work and the cross-cultural syntheses produced by Bandyopadhyay.

For many of us, myself included, Jarry was the singular beacon of that particularity, a writer whose theoretical stance defined an approach to aesthetics as an anti-method method, seizing a reality produced—and glimpsed—through the heightened experience of art and poetry. While this may seem a lost cause of Romantic aspiration in the face of administered culture, pending political and ecological apocalypse, and the dulling effects of current trends in identity aesthetics and other orthodoxies, keeping alive the belief in poetics as a way of thinking experience into form and being remains essential. Bernstein and Bandyopadhyay’s curious and creative critical work embodies the spirit of intellectual play essential to imaginary solutions—of which, perhaps, we have never had greater need. Bernstein’s notion of “frame lock” (an adaptation of Erving Goffman’s frame analysis)—the blindness that sets in when no intellectual movement can take place—feels highly relevant as a wake-up to call inaction into question. Is Brahma, action, the fulcrum point of poetry? Better consult Bernstein and Bandyopadhyay.

Further reading: Gestes et Opinions du Docteur Faustroll ‘Pataphysicien, Alfred Jarry, written in 1898, first published in 1911 available in English as Exploits & Opinions of Doctor Faustroll, Pataphysician–A Neo-Scientific Novel (Exact Change: 1996). https://web.archive.org/web/20150927044653/http://72.52.202.216/~fenderse/Dr_Faustroll.pdf

Ordering: For information on ordering the book, see: https://jacket2.org/commentary/pataquerical-ballad

n.b. I have one small quibble with Bandyopadhyay when she states that Sanskrit is the oldest language in the world, which it is not. (8) It is one of the oldest branches of the Indo-Aryan language and its emergence is dated to the second millennium BCE, about a millennium later than the Semitic languages of the ancient Near East. Evidence for the emergence of language before writing is scant, but some theories about its origin in Africa date it to the period when homo sapiens were becoming modern humans, around 200,000 years ago. 19th century linguists suggested that Indo-European was the oldest form and common source for non-Germanic European languages. The Vedas are the oldest Hindu texts, and the earliest of them date to about 1500 BCE. This is a minor point, significant only because of the often misleading mythologies that circulate about antiquity.

[1] Charles Bernstein, Attack of the Difficult Poems (University of Chicago Press, 1992). https://writing.upenn.edu/epc/authors/bernstein/books/attack/

[2] Fredric Jameson, The Prison-House of Language (Princeton University Press, 1971).

[3] Rabindranath Tagore, The Fugitive (London: Macmillan, 1921) published originally in 1919; cited by Bandyopadhyay, p. 77.

[4] Barin Ghosal, Otichetonar Kotha (On Expansive Consciousness), (Kaurab Publication, 1996), p. 22 as cited by Bandyopadhyay, p. 79-80.

https://www.college-de-pataphysique.org/

[6] Roger Shattuck, Introduction, Exploits & Opinions of Doctor Faustroll, Pataphysician–A Neo-Scientific Novel (Exact Change: 1996). xvii.

Superb. An entirely new context for reading Bernstein