Nanni Balestrini: “Art as Political Action, One Thousand and One Voices”

February 22-June 22, 2024 Center for Modern Italian Art, 421 Broome Street, New York, NY

Walking into the exhibit of Nanni Balestrini’s work at the beautiful Center for Modern Italian Art in SoHo, I was struck immediately by the variety in the collages made by this major figure in the Italian Neo Avant-garde. As I went through the exhibit in conversation with the Center’s director, Nicola Lucchi, and two researchers, my appreciation of the range of Ballestrini’s work deepened. So did my realization of the intellectual challenges it posed for critical interpretation. The works are not personal poems, nor are they simply formal works of art available to be read as self-evident. They are political works whose historical coordinates are an essential feature of their cultural, political, economical, and ideological value

.

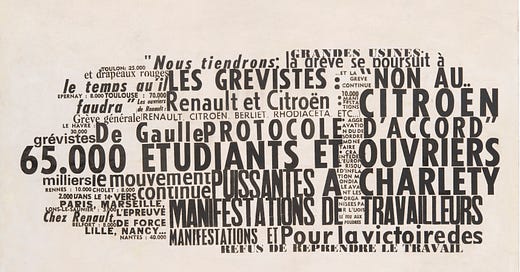

Nanni Balestrini, 65,000 Students, 1972, Collezione Emilia Mazzoli, Modena

Curated by Marco Scotini, with attention to the several distinct series in Balestrini’s output in the 1960s and 1970s, the works have a time-capsule intensity to them. These decades were an intensely volatile period in Italy, filled with labor unrest and protests as well as cultural changes that were part of post-WWII shifts in patterns of production and consumption. While the graphic features of these collages situate the works in the history of art and avant-garde literature, as well as the media of mass culture from which they are drawn, the texts require their own contexts for Balestrini’s profile to be fully appreciated. I felt immersed in another era, one whose aspirations for a future achieved by struggle drove the artist’s production.

The title of the exhibit, “Art as Political Action, One Thousand and One Voices,” calls attention to the “double acoustic and visual” aspects of his work. It also signals Balestrini’s commitment to a collective rather than individual voice. In addition to the collages, the exhibit features evidence of his decade-long collaboration with the experimental composer Luigi Nono, a reconstruction of an early work of computationally generated poetry, and his novels, which achieved a degree of popular acclaim in their depiction of labor uprisings and generational struggles.

But who was Nanni Balestrini? An artist, writer, and activist, he was a prominent figure in the post-World War II Italian Neo-Avant-garde. Saying that does not reveal much about that movement’s aesthetic contours, motivations, and its commitments to radical experimentation. To understand the its political and aesthetic dimensions, I had to gain some knowledge of the cultural context in which it arose, particularly because Balestrini was deeply entangled in these larger conditions. In what ways were the attitudes of these artists in the 1960s distinct from those of the earlier historical avant-garde, and related to the international networks of the period? To begin, however, I felt compelled to engage with the collages.

In the gallery, the variety and fluency of Balestrini’s use of appropriated print media is palpable. The collages are graphically vibrant pieces, and their material qualities have a visceral as well as aesthetic impact. While their communicative force would have been immediate at the time of their making, now their headline texts feel historic, and the archaeology of language in public discourse is vividly embodied in every detail of font, paper, and verbal expression.

Culled from newspapers and mass-market magazines, the collages are an inventory of the modes of media production of the period. Letterpress and relief printing, photogravure on high-speed presses, and photomechanical offset formed a wave of new technology that enabled color reproduction at an unprecedented scale. Photo documentary, consumer campaigns and marketing, and the language of journalism all flooded popular culture as electronic means of transmission began to replace mechanical ones from earlier phases of modernization.

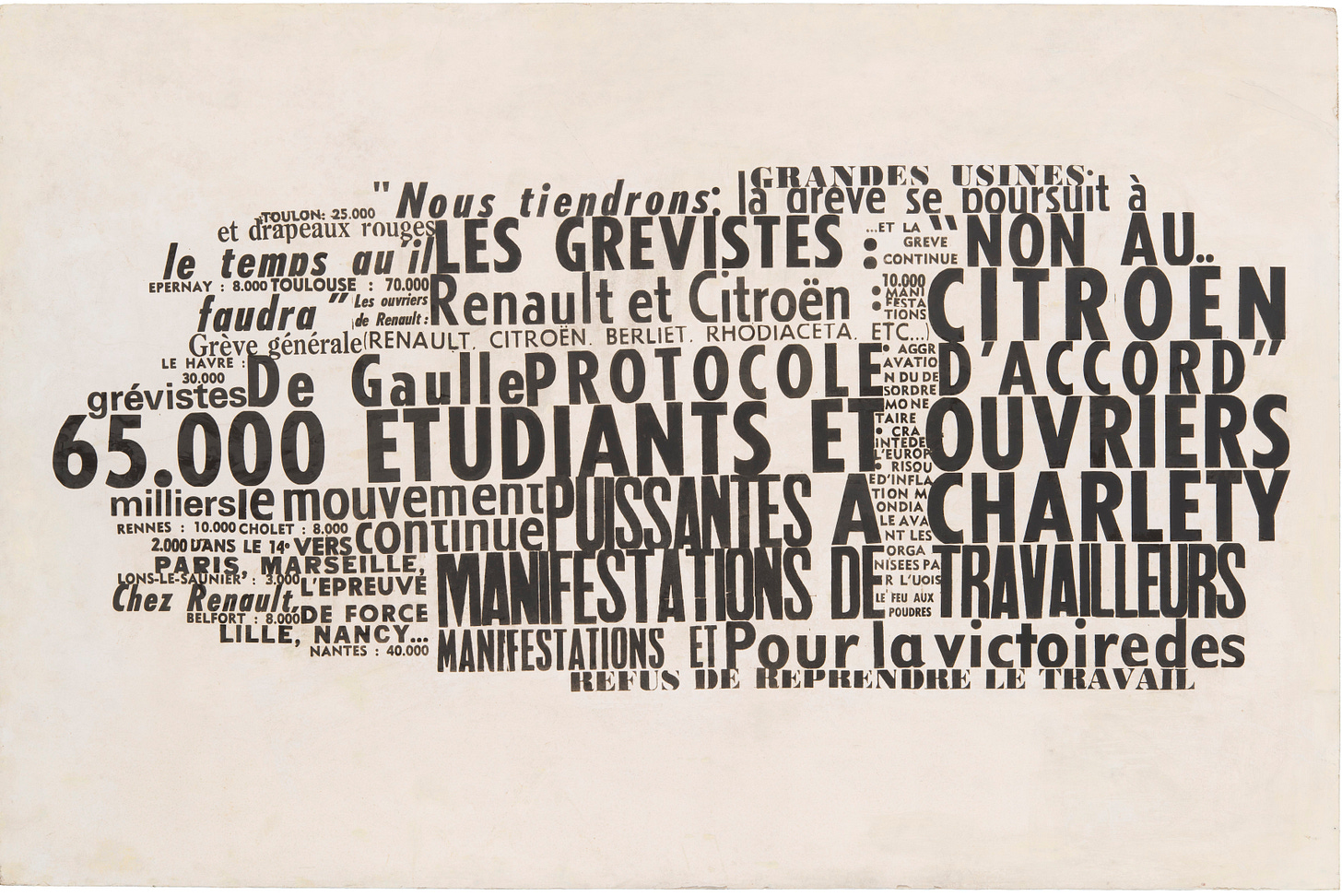

Nanni Balestrini, Cavallo (Horse), 1963. Private collection.

Thinking about this led me to reflect on the specific character of Balestrini’s collages. After all, despite precedents in 19th century scrapbooks and handmade albums, collage is a conspicuously modern mode of artistic production. Dada, Cubist, and Futurist artists all made use of the cut-and-paste appropriation of mass produced print media. Pablo Picasso’s Still Life with Chair Caning (1912) practically announces its modernity with pasted scraps of real material and painted references to the daily newspaper. Among other prominent figures in the early 20th century, Georges Braque, Hannah Hoch, John Heartfield, and Carlo Carra stand out for their distinctive use of collage techniques across a range of aesthetic and political positions.

But the collage work that Balestrini produces has no pictorial synthesis, no softening of message through integration or resolution. Quite the contrary. Brash, bold, confrontational, the fragmentary phrases have a highly direct in-your-face stridency about them, especially those that are slogans of struggle or acerbic political commentary.

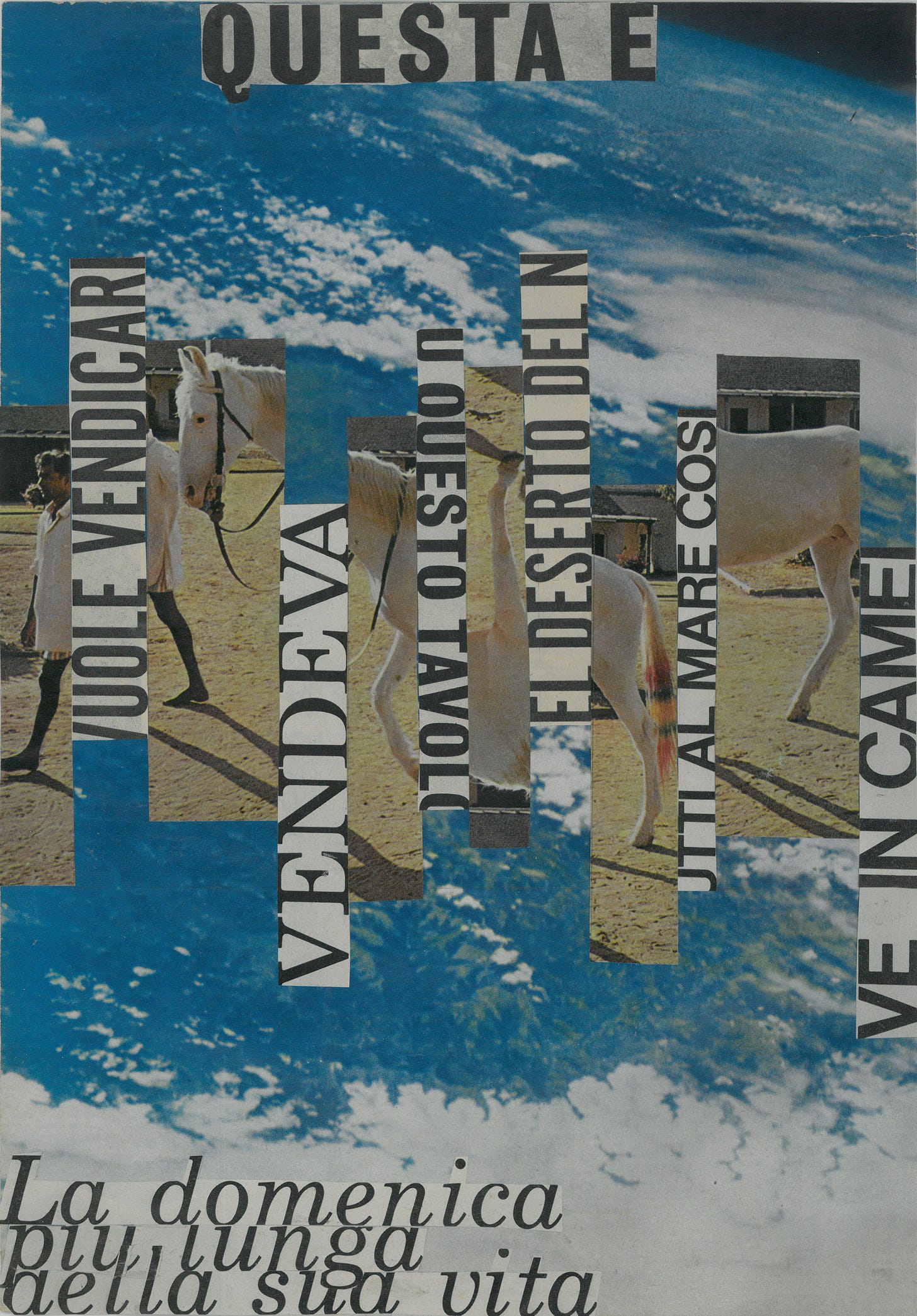

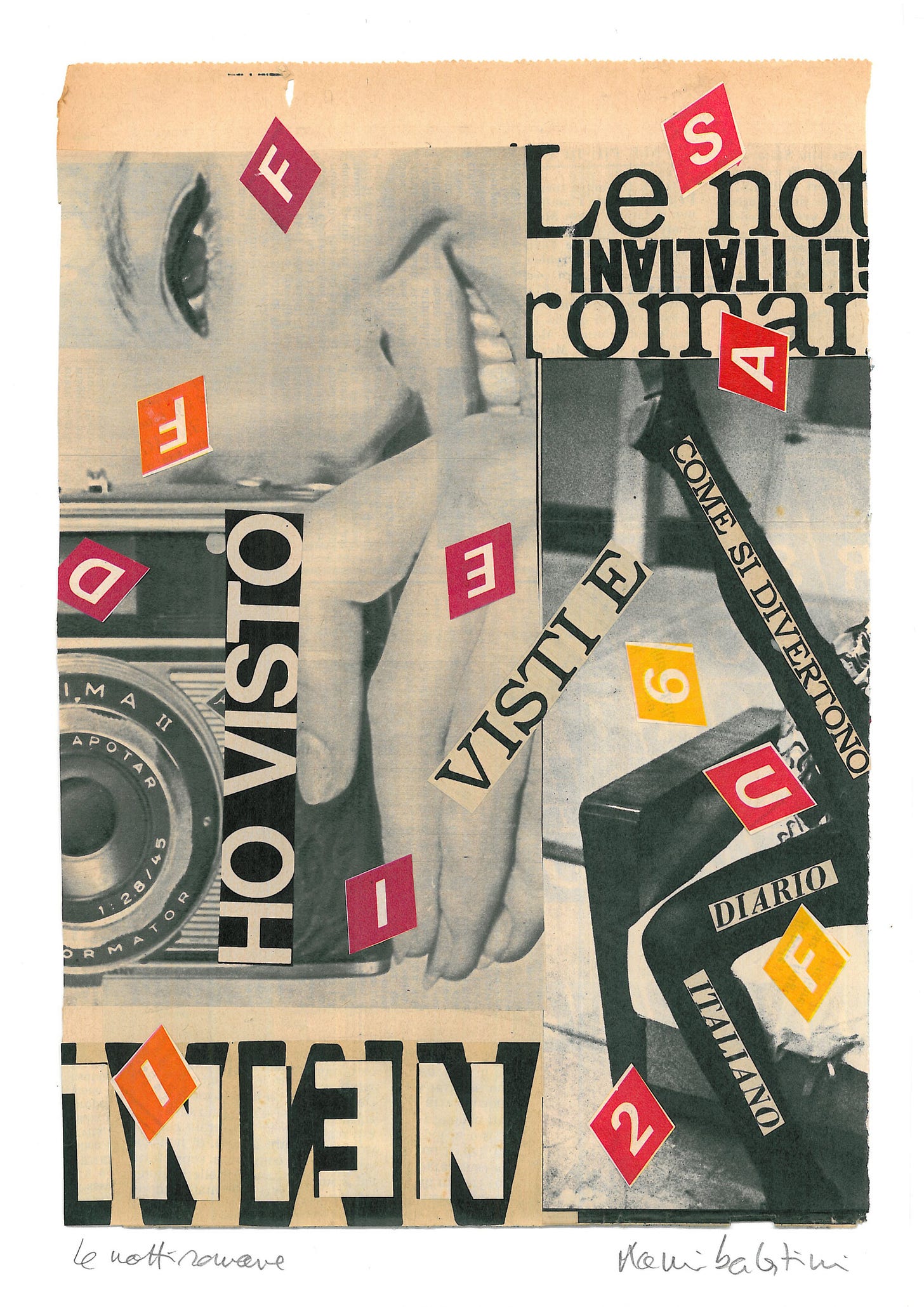

Nanni Balestrini, Notti Romane (Roman Nights), 1960s, Private collection.

Each collage series on display has its own sources, tone, and distinct compositional style. Some of the earliest are composed from glossy four-color magazines. For example, an aerial view of clouds on earth provides the substrate on which fragments of text in the 1963 Cavallo (Horse) state “he wants to avenge” “sold” “this table” “all to the sea like this” and “the longest Sunday of his life.” In a similar vein, Fear of Women 1965, The Mysterious Bodies 1962, Notti romane (Roman nights), Il regista (The director) also 1960s, are full of references to media industries and personalities, with glamorous figures in sunglasses or movie stars in highly polished poses. A sense of the pleasure of the 1960s lifestyle permeates the four panels of Magnifico, with scenes of sailboats and beaches, but the texts always have a more ominous edge to them, saying, “a voyage to the end of the world,” or “leave this cursed place.” The artist is clearly luxuriating in the materials, the easy availability of color imagery, but his commentary is far from celebratory.

Two works from 1964 echo grand themes of art, one contains scraps of Ferdinand Leger’s painting and is titled Card Game, another, The Grand Parade, is perhaps a reference to first generation Futurist Umberto Boccioni’s famous 1916 painting, The City Rises. The lines of connection and distance from early Italian Futurism are fraught in Balestrini’s work, and his identification with Left politics and radical movements position him against the Fascist leanings of Filippo Marinetti. But Boccioni’s heroic workers and transformations of the modern city have some connection with the context of industrial labor in which Balestrini’s radicalization occurred. Neither earlier nor later movements had a single unified outlook.

But Balestrini’s own alignment with workers’ struggles is explicit in the 1975 Potere Operaio (Workers’ Power) series, with language and newssheet pages taken from the workers’ newspaper. This series takes up themes from the 1960s Tempo series and a selection of text-only works from 1965, Il Mondo (The World), Contraddittorio (Contradictory), and others whose graphical organization creates bold emphases on the contradictions and violent subtexts present in daily media. By using the language of the press, Balestrini makes a poetics of the transformation of public/published language. The sometimes violently abrasive recombination of journalistic accounts into aesthetic works calls attention to the impact of media reports. Who speaks, what voice is heard, what authority and what contradictions ensue in the appropriation of language created by the press? What contrast with the traditions of poetry are manifest?

Nanni Balestrini, Cronogramma, 1960s-2000s, Galleria Michela Rizzo

Each work and series in the exhibit could sustain its own in-depth analysis. Cronogramma, a long series produced beginning in 1965, continued through the 2000s, again shows the compositional range of his work. These pieces have no background newssheet or magazine page. The strips of text appear starkly geometric in their arrangements, standing out against a black ground. Marshalled into vertical, parallel, diagonal, and perpendicular relations they are often taken from English-language sources, so the fragmentary phrases appear: “Crisis,” “me,” “down,” “the left,” “end war,” “ours but,” “my God,” “to die,” “terror in the.” The words hit with their direct blunt statement of events – “un diorno atteso da una vita” (“ a day long-awaited by a lifetime”) “poeta del nostril temp” (“poet of our time”). Slashed, sliced, and arranged with decisive precision, each work speaks volumes about how Balestrini is seeing the world and its representation in public discourse.

In the Quindici series, from 1969, the elements are laid onto the pages of that magazine. Black triangles that reference the aesthetic of Russian Constructivist Lazar El Lissitzky, and the angular dynamics in which strips of language used like vectors of energy and movement, create a distinct style for this group. By contrast, the Epoca works from 1971 make use of the black and white photographic pages of mass circulation magazine images, scattered with red lettering. They are clearly recognizable as a distinct cluster, and the imagery in these pages shows the conspicuous half-tone dot technology of production and images linked to that moment. Amazing how quickly one’s eye sorts details into those that appear “typical of the time” in which they were produced.

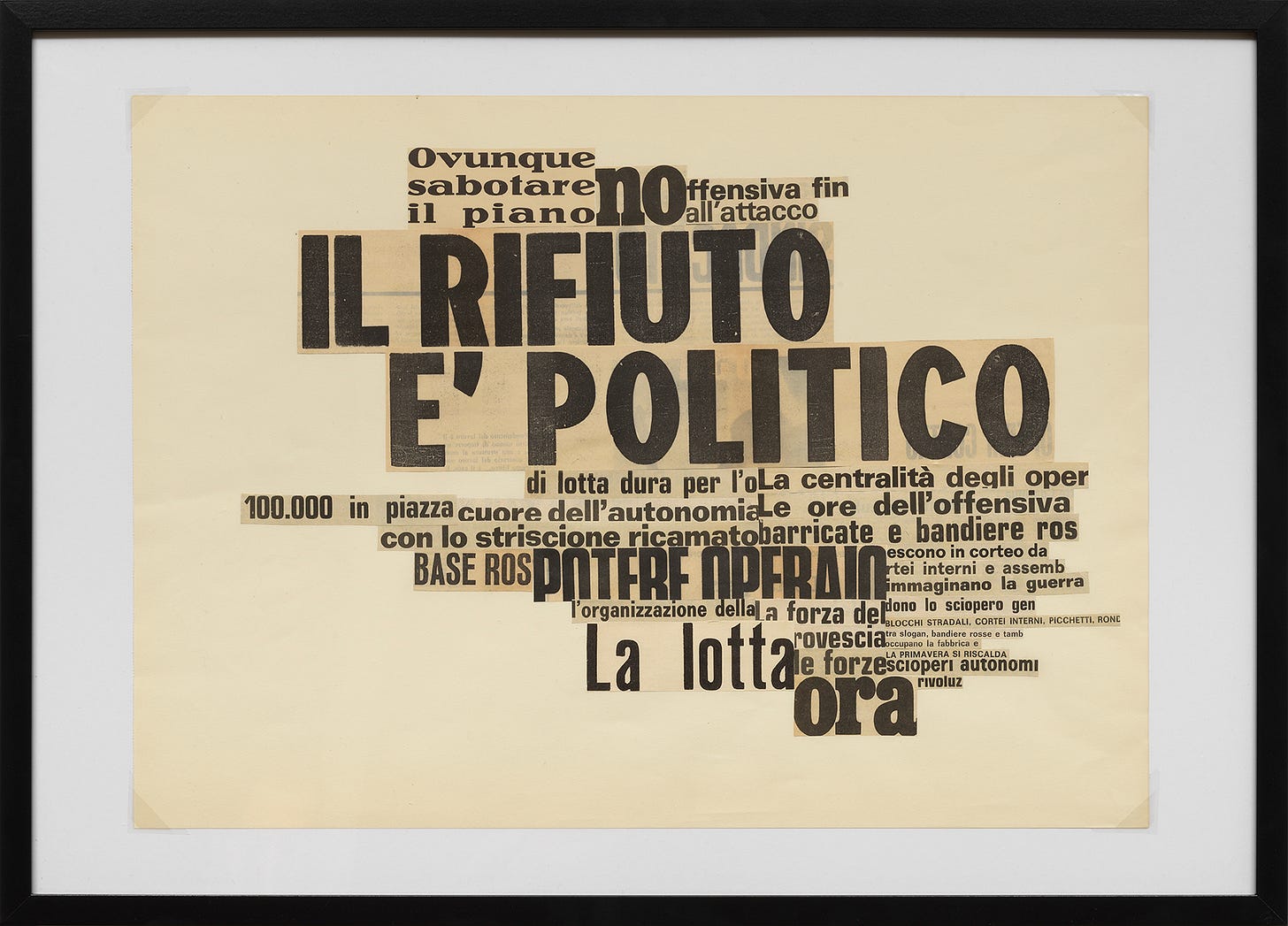

Nanni Balestrini, Potere Operaio (Workers’ Power) 1975, Private collection

But it is with the Potere Operaio (Workers’ Power) 1975 series that Balestrini’s association with the workers’ movement is most explicit. These collages, often using red and black elements and mostly on a field of newsprint, demonstrate the power of intervention in the discourse of political struggle. Strident and aggressive, full of bold statements, “Il rifiuto e politico” (“rejection is political”), they emerge directly from the record of protest movements and activities in which Balestrini participated. His sensitivity to materials, to the way newspaper columns, with their grid of text and the format of white space between structure the field, becomes a feature of his graphic language.

The Memoires d’exil series was produced from 1979-86. Balestrini had been accused of association with a terrorist group. Though never convicted, and quickly released from custody, he left Italy and went to France.[1] His exile was self-imposed, but also mournful. During this period he worked on a long poem, Blackout, which he saw as an elegy for a generation confronting the sense of the impossibility of effective revolutionary action.[2] In 1977, his novel The Unseen focused on the tensions between a young generation struggling for opportunity and free expression and the repressive power of the state. He clearly saw the artist’s role as that of documentarian and witness.

Balestrini’s commitment to activism was not an abstraction, an armchair indulgence, or a posturing stance. Struggle was not a thematic topic, but a real engagement.[3] Perhaps hard to remember, or imagine if one was not present in those days, the sincerity with which 1960s intellectuals aligned with students and workers with the goal of restructuring the economic and social relations of contemporary western culture. This was not a game, and the historical roots of the conditions in which such struggles took place marked the distance from earlier upheavals and changes, such as the establishment of Soviet communism, the two World Wars in Europe, economic depression, and the shifts in the fundamental structure of exploited labor and extracted wealth in industrial systems of production. In the 1950s and 1960s labor unrest in Italy was marked by struggles between the unions and the workers, as well as the unions and management.[4] Historian Sam Lowry notes that radicalization in Italian society involved cross-currents of influence between “university and factory” bringing about a “level of militancy unparalleled in Italy for decades.” Lowry points out the massive influx of students into the university system in the 1960s produced by larger patterns of educational change. The universities became a site of violent protest and struggle in Italy (and in France) in 1967-68. Major strikes against Michelin and FIAT took place from 1959 through the early 1960s and in July 1969 included a pitched battle in a public square in Turin between police and workers that lasted for days. Lowry suggests that the university education of young workers pushed their political consciousness so that by 1968 they saw themselves as revolutionaries in the cause of social reform. Groups formed to organize the struggle included Potere Operaio (Workers Power) of which Balestrini was a founding member. These were part of a larger movement of “workerism” Operaismo that focused on refusal of work as a major tactic.

Balestrini’s 1971 novel, We Want Everything, is an account of these struggles from the first person perspective of its narrator, based on militant worker Alfonso Natella and the Mirafiori plant and its exploitative policies. In the afterword, written in 2013, We Want Everything, Balestrini describes the central figure as a “type” he was portraying in order to make vivid the attitudes and circumstances of workers in Italy in the 1960s. In his own wrods, “It is presented as a novel, not so much as an invention of the imagination but as a forced operation to typify the behavior of an entire social stratum in one person’s experiences, creating a collective character who would personify the protagonist of the great wave of struggles of those years, in whom a new political figure appeared on the stage, with new characteristics, new aims, imposing new forms of struggle.”[5] The narrative begins in a mood of general disenchantment, with the protagonist cussing about every possible form of work available to him, followed by his decision to leave the South and apply for work at FIAT. Throughout, one gets a sense of the exploitation built into the structure of the economic system in Italian manufacturing.

All of this background is essential for understanding Balestrini’s work. But the aesthetic dimensions of his collages also engage with another critical twentieth century struggle—the identity of works of art in a mass media culture. By taking mainstream media materials as the source and matter of his production, Balestrini situates his poetic practice squarely within an arena where personal voice and private experience have no role. They are replaced by the articulation of a subject position. Balestrini speaks with the conviction that he is a part of a system, not a unique individual. This shifts the focus of artistic activity to an intervention in and through mass media culture. The romantic hero is banished, along with the lyric voice, and replaced by a report from the front, not heroic, just shouting.

Throughout the 20th century, as mass media gained influence and increased in scale, print culture saturated public space and discourse. Radio and then television even copied its formats—with “headlines” of the day, for instance, in newscasts and other features mimicking the journalistic conventions of print. Media representation of events produced the effect identified by Guy Debord as the transformation of everything that was lived into spectacle.[6] But the stance of art historical theorists, epitomized in the work of the Frankfurt School and especially Theodor Adorno, was that fine art’s role was to resist mass culture, distinguish itself in its substance, stance, and position from the mind-numbing production that posed a threat to critical thought. In a slightly different but related formulation, the American critic Clement Greenberg expressed this distinction in his famous opposition of “avant-garde and kitsch.” As the behemoth of media continued to extend its reach and influence on individual imagination as well as the larger construct of the social imaginary, this stance became the foundation of practices of conceptualism, minimalism, and artistic practices that defied consumption as their fundamental justification/validation/characteristic. But what form was such resistance to take?

Balestrini was not the only post-WWII artist to take the stuff of media as the foundation of his poetic practice. The British avant-garde Pop artists, members of CoBrA group like Asger Jorn, working with Guy Debord on an approach designated détournement, and even humorists like Monty Python, appropriated mainstream culture products and remade them into new work. Common to all of these works was, again, the rejection of the interior voice personal experience as the fundamental source for art making. In other words, the long long shadow of Romanticism was banished and in its place came a rethinking of the artist’s identity as a “detourning” subject, a pivot point, a strategic interventionist in mainstream culture from an acknowledge position as subject produced within it.

Looking at these collages now, at a distance of half a century, raises interesting questions about their relevance in the current context—but also, their relation to other historical works that make use of the ephemeral references in mainstream news media. What happens to work that is by definition situated within contexts that are time-bound and date-stamped? How do we understand and read it at a temporal distance—especially when that involves a cultural remove as well?

The Italian Neo-Avantgarde was part of the post-World War II cultural activity in Europe that occurred between the explosive innovation of early 20th century modern movements and a later capitulation to historical reflection in the postmodern vein. The modern avant-garde in Italy in the 1910s was most closely associated with the Futurists, whose visionary driver, Filippo Marinetti, followed a historical trajectory from experimental radicalism to Fascist sympathies. Reducing all of Futurism to its primary spokesperson’s politics would be specious, but Marinetti’s Futurist manifestos were shot through with destructive impulses as a way of clearing the stage for innovation including calls to destroy the Venus de Milo, burn museums and historic monuments, and above all, use war as the “the world’s only hygiene.” Radical innovation and destruction were linked, and the battle against conventional or traditional forms of art making is evident in the Neo-Avantgarde. Balestrini’s collages were an answer to the question of how to make a form relevant to the times, and here the line of continuity emerges.

Futurism’s materials were media even more than painting, sculpture, or literary works.[7] Marinetti had his first Manifesto published in Le Figaro, a mainstream newspaper, the night after it was written. Sound poetry, visual poetry, collage, all involved the recycling of material into aesthetic work where it was stylized as dynamism and celebrated as speed. No movement in the early 20th century understood the value of self-promotion through print and radio better than Futurism and its canny practitioners. Marinetti’s calls for radical innovation in typography, sound, poetry, and art were expressed in his technical and artistic manifestos. Who cared if any substantive body of work accompanied these proclamations. The promotional materials could suffice to make the claims.

Marinetti’s first Manifesto appeared in 1909. Then the devastation of the First World War sobered the generations that participated. By the 1920s the complex political maps of Europe shifted allegiances inside and outside of national boundaries. Nationalistic movements came increasingly to the fore in Germany and Italy even as the Communist Party, founded in 1921, and outlawed under Mussolini, served as a site of resistance. From the perspective of a century later, the complexity and intensity of politics in the period are difficult to recover without in-depth study. But the activities laid the foundation for the climate in which the Neo-Avantgarde arose—a climate vastly different from that of the 1910s in which the avant-garde of Marinetti’s Futurism came about.

In the aftermath of WWII, the growing international dimensions of modern art were also countered by various more local formations. Some post-War movements rapidly achieved international recognition and participation. These included the Situationist International, Fluxus, and Conceptual art broadly defined, among others, but the Neo-Avantgarde as developed in Italy was not among the more prominent. We could look to Italian New Realist cinema for parallel interests and influences, but formally the Neo-Avantgarde was far from its narrative or representational conventions.

Balestrini cites references to his aesthetic lineages. Futuristica (1969) depicts a man in the suit and hat, the perfectly dressed figure that reminds us of the early Futurists in their bourgeois dress, attacking the very system that had produced them. The faces are erased, but the postures and costumes remain along with references to the “Teoria e invenzione Futuristica”.

Balestrini was not a Futurist, nor is his work derivative in the narrow sense. But his sensitivity to his own condition as a subject of history, produced by the circumstances of his location and position, makes his recognition of that historical past—and its defeats as well as insights—important. Futurism’s optimism became corrupted, to be sure, and stigmatized. Moving beyond that was imperative.

Still, in a poignant recognition of that historical past, the exhibit included two ink-on-paper drawings by Carlo Carrà made in 1914. More than a century old, the visual poems are deeply affecting. Schematic and diagrammatic in their dynamic formats, they still spin with high energy aesthetic vision, Futurist works fully realized as those “words in liberty” called forth by the manifestos. Modest in scale, hand-drawn, they have the potency of the early working out of radical ideas in other fields, such as quantum theory and relativity. Carrà’s dynamic graphic equations were spring loaded to launch a revolution in thought, which they did.

Balestrini’s work remains compelling and absorbing. The visual and verbal texts demonstrate the inseparability of material (sonic, graphic) expression and semantic value. They also preserve their original force and compelling aesthetic quality as documents of a different moment of political optimism and commitment when the notion of creating a collective voice seemed possible and desirable. I never met Balestrini, but the charismatic quality of his presence comes through the work, offering a conversation across a gap of time and location. The exhibit deepened my understanding of his work, but also, of the challenges of reading and understanding pieces when their contexts of conception have vanished. I have no sense that I have given Balestrini’s work it due. Better go and look for yourself.

[1] Harriet Staff, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/harriet-books/2019/12/peter-valente-illustrates-the-moment-around-nanni-balestrinis-blackout

[2] Ibid.

[3] Benjamin Noys, “Fiat has Branded me: A Hot Autumn Timeline for Nanni Balestrini’s We Want Everything. Verso News, 22 June 2016. “https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/news/2711-fiat-has-branded-me-a-hot-autumn-timeline-for-nanni-balestrini-s-we-want-everything

[4] https://libcom.org/article/worker-and-student-struggles-italy-1962-1973-sam-lowry

[5] Nanni Balestrini, “Afterword 2013,” We Want Everything, English version. (New York: Verso, 2016)

[6] Guy Debord, Society of the Spectacle, Red and the Black, 1967.

[7] A contrast could be made to Surrealism, which took dreams and the unconscious as material, or Cubism, in which the stuff of ordinary life resulted in still life painting, or studio studies of nudes and bathers, or Post-Impressionism, with its emphasis on landscapes and portraits. Futurism and the conceptual moves of Marcel Duchamp are the real harbingers of later 20th century aesthetics.