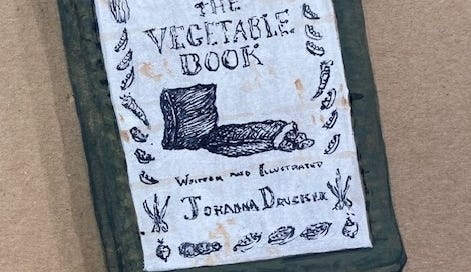

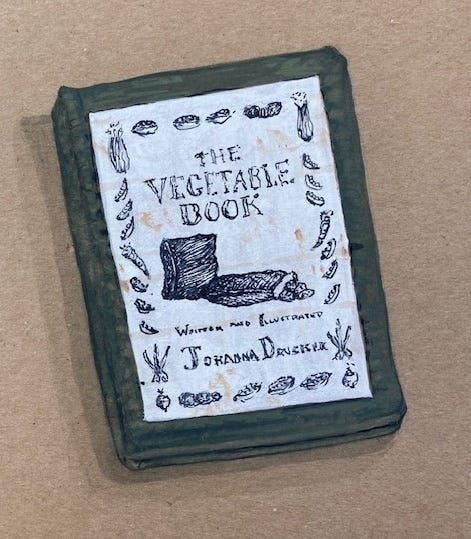

The Vegetable Book, 1973, cardboard covered in cloth, paper cover, hand-bound. Gouache and watercolor, 2025.

In 1973 I was twenty years old, living through the winter in a rented summer cabin on a lake in Connecticut with my then boyfriend, an earnest aspiring musician who was a committed vegetarian. I was trying to figure out how I was going to make a living after I finished art school that spring and one fantasy that took hold of me was that I might be able to succeed as a children’s book author or illustrator. So I wrote and drew a series of one-of-a-kind books with vegetables as characters: The Fruit and Vegetable Book (in two versions), The Vegetable Cookbook for Children, and the full-length Tomato’s Rescue, an adventure story. The books never saw the light of day, and remain relics of optimism, time capsules from a winter of isolation and naively unrealistic expectations.

The cabin was almost unheated, and we were on short rations all around, scaring off the heating oil truck when it arrived since the bill was an astronomical sum, nearly the equivalent of a month’s rent. I was living on a tiny nest egg I’d earned from an exhibit of my work in San Francisco the previous November, and we survived on bouillon cubes, brown rice, and endless cups of hot tea. American involvement in the war in Vietnam was blundering to an end and I listened to the evening news on a tube-powered radio housed in a large wooden cabinet with built-in speakers and a turntable. I drew constantly, absorbed by the capacity of the crow quill pen to create sensitive fine lines. The cost of ink and paper were considerable by my standards, so I took care to use them judiciously. The one resource I had in abundance was time to concentrate. My boyfriend practiced scales and stride piano, played Scott Joplin ragtime, Charlie Parker tunes, and Louis Armstrong classics on the turntable. We looked out at the frozen landscape which stayed grey-brown and hard bitten almost into May and both worked with steady diligence at our labors. We saw no one except each other. We didn’t know anybody, and the unfamiliar vacation community was shut down for the winter.

In The Vegetable Cookbook I put very simple recipes that included basic information about vitamins and methods of preparation meant to preserve the nutritional value of the food. These were pre-Internet days, of course, and a time before digital production or research methods. I cut the paper with a knife, drew out the patterns, inked them in, and carefully lettered the rhymes directly in place. The books could have been made at almost any moment in the prior centuries, though the plastic pen holder and the availability of tablets of hot-pressed Bristol paper were recent innovations.

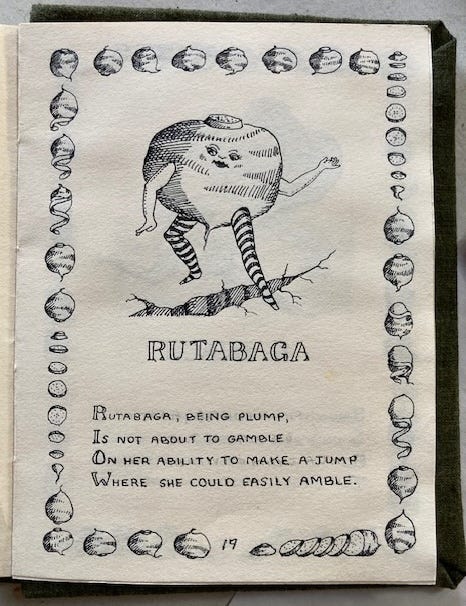

The rhymes in the first version of the book are four lines each, and caption the drawings of vegetables that have rounded limbs and appealing features. The poems are fraught with danger, disappointment, and threat—hardly the thing for young readers. I was completely unaware at the time, just coming up with rhymes that seemed clever, that the world I was conjuring was full of cracks, ruptures, hazards, and dire consequences for everyday actions. Now, I see the perversity of a poem like this:

Rutabaga, being plump,

Is not about to gamble,

On her ability to make a jump

Where she could easily amble.

Or

Avocado what a mess you’ve made,

Lifting out dirt from the planking.

And you’ve muddied the shoes in which you played

It seems you shall get a spanking.

“Rutabaga,” from The Vegetable Book. Pen and ink original, 1973.

Corporal punishment has fallen out of favor and parenting modes changed over the last half century, but these vegetables behave in accord with the vanished paradigms. This first book was badly constructed and bound using corrugated cardboard and rubber cement, a deadly combination destined to self-destruct. Ripples in the cloth follow the contours of the substrate and foxing and paper rust have grown in the hills and valleys. As an object, it is a testament to the liabilities of amateur construction.

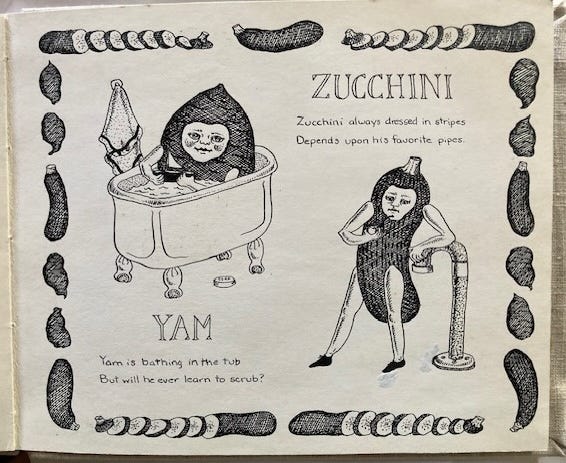

This version of the book was quickly followed by one that was slightly better made, though the basic design of the pages—drawing, rhyme, and borders with delicately drawn exquisite motifs–was the same. The compressed two-line verses are even more perverse in tone:

Yam is bathing in the tub

But will he ever learn to scrub?

“Yam” and “Zucchini” from The Vegetable Book, 1973. Pen and ink original

Pear, pear, your little legs are thin

You need some socks to keep them in.

Pepper sitting on a wall

Have you nothing to do at all?

Or this one accompanied by a cucumber with sweat pouring off his brow:

Cucumber carries a heavy sac

All the way to school and back.

A wonderful economy of graphic means echoes the succinct verbal style in these works, which are droll in their way, conceived in a spirit of (dark) whimsy. They belie the apparent innocence of the theme, and perhaps reveal something about the underlying psychic stresses of domestic austerity permeated by an atmosphere of political/cultural uneasiness and personal uncertainty. I sent the books to an agent, following on a positive response to a query sent by mail to and from our local post office where we had a box with brass fittings, relic of another era. I went to New York, looking for work among the publishers with lists of children’s titles, a small black portfolio in hand. One editor, concerned, asked me if I knew how to find the subway to get home again. I felt like a heroine in a fairy tale mounting staircases to visit figures of magisterial power and mysterious abilities. Nothing came of those attempts, but I persisted.

Tomato’s Rescue, 1973, Pen and ink cut-out on cloth-bound cover.

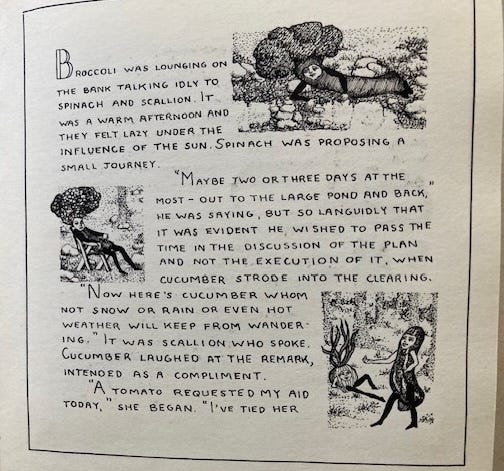

Tomato’s Rescue, 1973, interior page, pen and ink original.

Tomato being cut free by Cucumber, Tomato’s Rescue, 1973, pen and ink.

The final book in the vegetable series was Tomato’s Rescue, a story of the heroic efforts–ultimately successful–by a cucumber and zucchini trying to save a young tomato from an unfortunate fate. Echoes of Beatrix Potter run through here as the threat to end up in a cooking pot is held out as a very dark future. Completely hand-drawn, the book feels closer to the 19th century than the 21st, its details rendered in an illustrational style that I had clearly channeled from some childhood reading experiences. And in fact, this aspect of these works is what I find most interesting, that they pull from an inventory of memory sources to create a world of vegetable characters in terms that at first seem to conform to the conventions of children’s books, but turn out to have a weirdly distinct perversity to them. I was writing other “adult” illustrated unique books at the time, Light and the Pork Pie, for instance, which begins, “A pork pie gone dancing in need of romancing now stumbling now fumbling incipient mumbling at errored ways plays by herself in the dark.” Full length, illustrated with watercolors, hand-lettered with the same crow quill pen tools as these vegetable books, it is further evidence of the poetic idiolect in which I wrote in my late teens and early twenties. The psychological world I inhabited was even stranger than that which I conjured for the vegetables.

Fifty years later, I wonder if some vegetarian-friendly editor be interested in publishing rhymes about the existential plight of vegetables faced with the complexities of daily life? Unlikely.

Thanks for your note! Much appreciate it. I will look for the reference. Cheers!

I will join the others in the sentiment that these should certainly find a publisher, they are truly delightful.