My Unread Bible

My Unread Bible

On my first day of kindergarten my mother took me only inside the door to the classroom. We stood together for a moment and I hesitated before going farther. Ahead of us was the crying table whose purpose I didn’t understand until some hapless child was abandoned there a few days later. My mother averted her gaze. Her unwavering bite-the-bullet principles pervaded her child-rearing.

I knew not to flinch, but I felt trepidation. The room was hushed and I did not understand what ritual was in play. I was processing a completely unfamiliar scene. Why were all the children silent, sitting on the floor cross-legged, focused forward, faces registering differing degrees of attention on their features. The silence was unnatural. My mother leaned forward for a moment, already withdrawing the temporary protection of her elegantly slim body in its navy cardigan and long pleated skirt. Over my shoulder she gestured into the room towards an empty place in the front row of the seated children. I had to go.

I skittered into the spot, sinking quickly into the seated pose, my little dress neatly spread over my knees in a self-conscious arrangement. Girls wore skirts to school, always, every day. Next to me, another girl sat quite composed, clearly habituated to the scene. At the front of the room the teacher, in a narrow dark dress that emphasized her thinness, stood with head bowed. Her curly dark hair was cut close to her scalp and the nape of her neck. This was Miss Rosenfeld, the kindergarten teacher, whose chaste appearance signaled resignation and acceptance, as if she had left all expectations for personal fulfillment long behind in taking up a life of duty. I hope that was not really true, but we sensed that she had been sentenced to kindergarten for life.

She was holding a book in her hands and reading aloud. This meant nothing to me, so I turned quickly, stealthily, to the girl next to me and whispered, “What is your name?” She shushed me so fast I hardly registered a gap between my question and her response. “She’s reading the Bible,” she said, still looking at the teacher whose attention had already been attracted by our exchange. The disturbance broke the quiet concentration of the room just long enough for me to know never to repeat such an action again.

But the Bible? What was that? The book bound in dark black leather, its ribbon place-marker hanging, was an unfamiliar object. The pages were edged in red, the volume draped open in the teacher’s hands. Intuitively, I sensed its significant gravitas. The reading was ceremonial, not narrative. Miss Rosenfeld’s voice had a solemn cadence to it. I could not make heads or tails of the text. In its coded language “valley” and “shadow” and other terms clearly carried meaning beyond the kind of descriptive operations I was used to in hearing stories read aloud. At age five, my own reading abilities were still elementary, and neither word recognition nor intellectual comprehension went much beyond two syllables. The land of metaphor was largely unknown and the realm of symbolic thought as distant as the outer galaxies. This was only the first day of kindergarten, after all.

My mother had vanished by the time the Bible reading was finished. Her job was done. She never burdened herself with an excess of nurturing. I was on my own among the wild things of my generation, left to find my way in the social world of cubbies and nap times, squabbles over friendships, loyalties, and occasional betrayals. The kindergarten room was its own arena of social dynamics and we formed little energy fields configuring and reconfiguring on a daily basis.

But the Bible? The identity of this potent volume hung as a question I could not quite formulate in my mind. I didn’t even know how to ask what it was, so unfamiliar I had no reference frame within which to pose the question. Religion was uncharted territory, at least with regard to beliefs. I had only a social sense of affiliation. We identified as Jewish, but tenets of belief did not factor into our self-description. A girl who lived down the street from me was Catholic, so that meant she went to a different school and wore a uniform. These differences registered as significant, though without a gloss on what the substance of those distinctions might be. I went to Sunday school with my brother on mornings when my parents were awake enough from their late night partying to see us out the door or take their turn in the carpool.

Sunday school had its own torments, beginning with the scratchy starched edge of the crinoline sewed into my dress. This rubbed my belly and caused welts so that I associated a distinctly non-Jewish mortification of the flesh with the weekly attendance. But Sunday school also meant glimpses of Rosa, a four-year-old outfitted like a candy-box with a wide satin ribbon around her waist, a cloth flower attached. The faded rose petals were the same color as her lips. I had a velvet purse with a little gold chain and petted its soft pile through the service, looking sideways down the row of chairs towards the beautiful Rosa. The Bible never showed up in these situations, instead, a large decorative scroll, taken from the ark, was unrolled on the pulpit and a silver pointer used to follow the Hebrew text of which I understood not a single word. I could not connect those shimmering objects with the soft dark volume Miss Rosenfeld had held in her hands.

Religious symbols introduced considerable confusion and consternation in my young mind. What, in fact, was a cross, that ubiquitous and mysterious symbol of another world into which I had not been initiated? I lacked any formal instruction in these matters, my parents being dedicated radical humanists with a profound antipathy to organized religion, both having been raised in rather too-orthodox households of different faiths. So I was left to decipher these matters on my own, without guidance. One day my brother and I watched a movie about a coming apocalypse brought on by nuclear testing—this was the 1950s after all. The film had a long slow shot of a cathedral whose rooftop cross was glowing gold in the final light of the world. I wasn’t sure if I should watch it or not. I closed my eyes, afraid that the symbol might be something I was not supposed to see. After all, there were no crosses in my environment—nor Jewish stars or other religious icons. My mother believed in the spirit of all animate things—trees, rivers, waters, winds—and these could not be pictured, only felt. Still, I was frightened by the image of the cross, worried I might be cast into some unnamed and unfamiliar hell because I had witnessed this image without belief. The sense that it had power to which I might be subjected was profound.

And so with the Bible, that volume of densely codified text, its mysteries and messages barely legible to me as a child. We learned a little of the five books of Moses, and concepts like Creation and Exodus took hold, but without much conviction. My family’s dinner conversations were filled with tales of space travel, other dimensions, and the mysteries of scientific frontiers. Marx, Freud, Einstein—and the Marx brothers—were our patriarchs, spiced up with a smattering of Matisse, Byron, and Shakespeare, and if there was a bible in my house, I never saw it and certainly never heard it read.

I remained confused for many years about the categories of “our” Bible and “theirs”–why were there two–and how they were different. I worried that theirs might have traps and that I might find myself ensnared, tricked by beliefs, if I listened to this “other” text. The power I accorded to the Bible was enormous, and real, even if—or maybe because—of my ignorance.

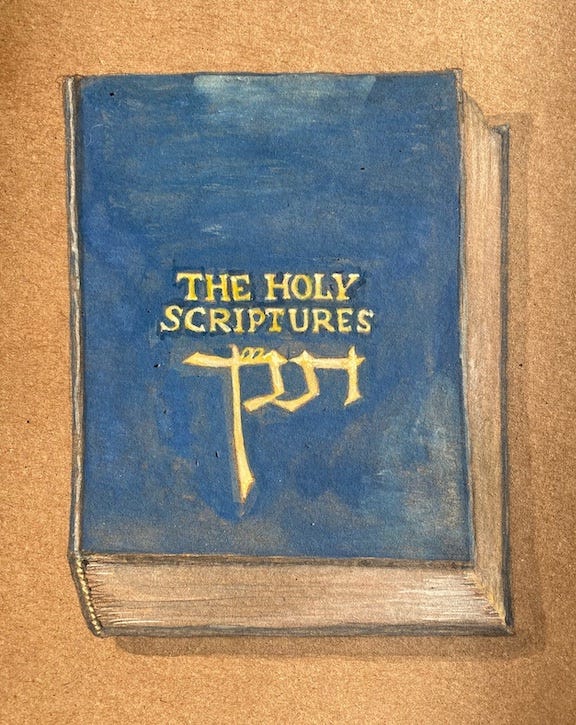

So I grew up, a little unlearned pagan in my parents’ house of humanist thought. The Bible I have never read, acquired at some now forgotten adult moment, is the Masoretic translation. The text is in English, and the pages follow the left to right sequence of reading, but the chapter headings are in Hebrew, a reminder on every page of the community responsible for this source. My copy still remains largely unread, a reference text to be consulted time to time. I have the vague promise to myself to read it one of these years ahead, engage with it as a work of history and literature, safely insulated by intellectual rather than religious study. For now, it remains almost as unknown as it was that first kindergarten morning, when its reading called for protocols I did not understand, which got me slapped by the little girl sitting beside me on the floor. She became my best friend, as fate would have it, we bonded as tightly as if the empty space next to her had been the outer shell of an atom and I was a free electron.

Now my modest, unread volume, with is worn edges, soft paper, and utilitarian honesty, opens well and offers its pages to view without resistance. But it is still latent with potential. Though I no longer fear to look on these symbols of religious belief, I remember how confused I was without a guide for what I should, might, could read without risk.

The only other bible I knew intimately was a family heirloom, a tiny bible in soft black leather with a self-closing flap that protected its gilt-edged pages. That volume had been carried by one of my mother’s ancestors, “Will Kerns,” who was a soldier in the Union Army and had received it from “Nellie” in March 1864. The book served as calendar and diary with notes on the edges of pages indicating where he was when he read them. So in his neatly penciled hand the marginalia records a “skirmish” near Adairsville date May 17, 1864. Almost a year later, “Chattanooga, March 29” and “Knoxville, March 31” appear a few pages apart. “Jeff Davis caught” is stated on the edge of a passage of Jeremiah. In the Letter from Paul to the Corinthians, he wrote “Read the 8th Chapter, New Orleans, August 13th, 1865.” Replete with history and memory, that small volume was evidence of a time in which the Bible was what one carried, what one read, where one turned in daily times of uncertainty and trouble. The volume served for ritual reading but also a place for writing, a basic framework for a life unfolding. On the final page, in the blank partial sheet after the end of the “Book of Revelations,” he wrote that he had “commenced to read this bible, a present from a friend, while home on a veteran furlough.” He also claims that he had read it through again in from start to finish and in parentheses in the gutter he added the words “good boy.” Unless it was someone else who followed his progress in that text, recognizing his effort, and offering a reward on earth.

Thanks so much for this comment, and yes, it was you I sat next to that first day. Retention drills and Crayola crayons indeed. As to your reading to your brothers, I knew nothing of that, but I can picture the seriousness with which you would have subjected them to the experience. Glad to have known you all of these years.

What a remarkable memory you have! I forgot all about the bible being read to us in kindergarten and have no memory of Miss Rosenfeld's cropped hair or plaid skirts. Of course I remember being that little girl who shushed you, but I don't remember the slap. My most vivid memory of kindergarten is the oft visited vision of a certain B.B. shuffling out of the bathroom with his drawers around his ankles. Remember the Retention drills and sitting silently on the floor against the hallway walls? That and the tiresome lights out nap time lying on the classroom tables surrounded by the smell of Crayola crayons, school paste and the barely audible slow tick of the second hand on the big round clock on the wall marching around its circle until lights on.

I did have my own bible from a young age, delivered to me by the scary skinny spectacled woman from the church up the street as an enticement to go to Sunday School. It remained unopened until several Sundays in my third grade year when I forced my two brothers to sit silently locked in my bedroom in order to listen to me reading THE BIBLE out loud. Though I was sure that was where my father was headed, I wasn't about to have us all doomed to an eternity in hell.