I was ten when my family took an eight-week summer vacation driving across the country. We car-camped most of the way, belongings efficiently packed in the family station wagon. We were a well-organized team and could set up or strike camp in record time. We staked the two sleeping tents, stretched the dining tent cords to create a screened outdoor room, and unpacked the kitchen gear unit carefully designed by my mother with pipe legs that screwed in and out of a plywood box that was both food pantry and utilities cupboard.

My job had been to plan the trip with my mother. Through the Spring we sat after dinner with a road atlas open and I did mileage sums in my head to sketch distances for each leg of our travels. We left from Philadelphia, drove to Gettysburg, and then followed the Blue Ridge mountains south into Appalachia and the Great Smokies before heading west to tour the major National Parks. Zion, Bryce Canyon, the Grand Canyon, and Tetons were all stops along the way. Each had its dramatic landscapes and natural features. We gaped at bubbling sulphur pots and stared in wonder at cliff faces striped in vivid colors unseen in the older geology of the northeast. Summer thunderstorms of a scale unprecedented in our experience appeared in these enormous landscapes, visible as they moved across the plains, black with rain, turning the sky a bilious green as the lightning struck and thunder cracked. More than once, we pulled over on the side of a steep mountain road and sat in the car, reassured by its rubber tires, and played cards while the violence raged. My parents were intrepid but not foolish. They, too, were experiencing these scenes for the first time.

In urban centers we stayed in motels or hotels, but for the most part, we were in campgrounds where ranger-led programs introduced the local flora and fauna. The stars were bright in the night sky, far from light pollution. This was 1962, and if summer vacation had a popular image it was of families in station wagons. We were generic in that sense, a family of five eating bacon and eggs for breakfast, baloney and cheese sandwiches at lunch, and hamburgers for dinner while travelling to “See America.”

We visited a handful of relatives along the way. My father’s family was in Skokie. They were short, stout, resilient Jewish people adept at creating family mythology. The eldest daughter among father’s cousins was unmarried, with bleached blonde beehive hair, tight skirts, designated as supremely competent in her work as a book keeper. The younger sister had faded into marital lassitude. The baby brother had screwed his neighbor’s wife practically in plain sight of his wife on the lawn of their home in a classic middle class suburban neighborhood. Scandalous, of course. Though he married her following a bitter divorce, the new wife became known as “the slut” in the blunt language of the time. Fun, pretty, and vivacious, she appealed to my naïve understandings in ways the eclipsed spouse never had. The fallout of these events was the fractious schadenfreude of families—who takes sides with whom? Alliances required we chose to be loyal to the “slut,” the brother, or the betrayed wife who was not the sister of the others.

My mother folks were in Downer’s Grove, severe people. We visited them on the return trip for a few days of immersion in sharp judgments and continual reprimands. But my mother also had a brother and a sweet older aunt in California. We visited my uncle in their bungalow near Palo Alto where our teenage cousin had just gotten her junior license and could drive. We were so impressed. She wore sandals, a silver bangle bracelet, and had blonde hair in a perfect pageboy. I doubted we were blood relations. She took me and my sister to a chain restaurant, a Denny’s or some similar place, where we had cokes and fries and ate on our own without the parents. This glimpse into California early adulthood was alluring, as was the light in my mother’s aunt’s kitchen in the morning, slanting long and warm across the counters to a cookie jar with lemon crisp sugar cookies, homemade, of which I consumed a considerable number, more than my share or than was good for me. But the golden brown crunch leaked buttery sugar onto my tongue with a sensation I could not resist. And of course, because the aunt was part of my mother’s family, cats were present. We missed ours, Gwendolyn and Reginald, left at home for the summer in the care of our house sitters. Therefore the presence of Fluffy or Misty or whatever spoiled feline creature was in the household was an extra benefit. Children remember these landmarks in a long journey: thunderstorms, pretty cousins, cookies, cats.

And then, there was San Francisco, the beautiful “city by the Bay” then referred to in common speech as “Frisco,” a term now vanished from the language. We had never seen a city so spectacular, perched on hills above a shining sea, wraithed in fog, its hills so steep they defied the laws of driving. Everything was picturesque and matched the touristic images of promotional literature—cable cars, the Golden Gate Bridge, and the bustling activity of Fisherman’s Wharf. The cold was noticeable. We had summer cardigans and of course wore dresses—little girls did not wear pants in public in those days, only in campgrounds and places of sport. On the brisk windy piers we were shivering, bare legged in cotton clothes. We could not fathom this. California was the land of sunshine, beaches, bathing suits. We had been warned, but like many hapless visitors, did not believe summer in San Francisco could be so chilly.

We wandered into Chinatown, a destination also touted in the tourist literature. We had an Asian neighborhood in Philadelphia, a tiny enclave of shops in a few blocks north of Arch Street, where my mother went to buy authentic Kikkoman soy sauce for a marinade recipe given to her by a Japanese friend. But in San Francisco the community was thriving, picturesque in its exuberant expression of Asian culture and trade. The sordid history of exploited labor and the Exclusion Act of 1882 were nowhere visible. The streets were hung with lanterns, brightly festooned with all the red and gold trappings of a festive atmosphere. The storefronts were crammed with goods—sandals and embroidered clothing, parasols and wallets, paper cuts and brightly painted ceramics. Overflowing, teeming, abundant the merchandise was meant to tempt the tourists and succeeded. The crowds streamed in and goods flowed out in a constant and unceasing circulation.

We were thrifty people, not inclined to impulse purchasing or the consumption of useless things. Our summer allowances were carefully monitored. Conversations on what and when to buy anything at all were measured as well. But this was San Francisco and acquisition of some memento of our having arrived at the Pacific Coast, of being at this far edge of the Continent for the first time in all and each of our lives, seemed in order. What to buy? The china dolls with their stark faces, black wigs, and stiff limbs were emblematic, but too obvious. A fan had no appeal, it didn’t do enough, could not be repurposed to any activity besides the one for which it was constructed. Large objects were prohibited on account of our circumstances of travel, and who wanted a folding stool or screen in any case—they would have had no place in our Federal era house in Philadelphia, with its small rooms edged in molding, wainscoting, and other features of a radically different style of domestic interior. Ours was not a home where exotic trophies found a place. My parents were inclined to Knoll chairs and mid-century modern décor, spare, classic, even conservative.

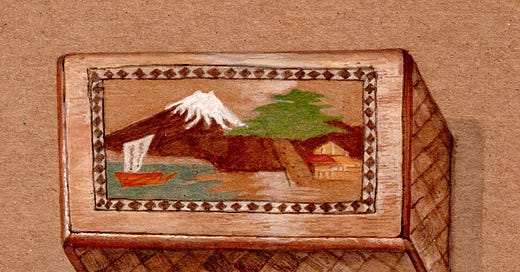

So my souvenir purchase had to be something personal, motivated by my individual tastes and interests. And I found it. A puzzle box. Wood inlay, neatly made if mass-produced, it seemed a solid block at first, impenetrable. My eager fingers, never quite as clever as I imagined them to be, only slowly found the secret by which a slotted strip slipped to one side, the top panel edged back, another piece moved upwards, another down, and the interior space was revealed. The secrecy appealed to my ten-year-old self, as if the inaccessible and private chamber were that part of me that had not been discovered by others, but which I knew was there, waiting, filled with potential for future development. Something vaguely sexual attached to my associations, as if that shielded interior were a point of intimate access, still hidden, private, kept locked away.

I purchased the box, thrilled by my new possession. But what to put into that secure interior? What treasure merited the privilege? What thing among my belongings could bid for such a spot?

The answer came in a peculiar form, fulfilling another hidden dimension of my spirit. I had, somehow, developed a desire to have a suicide pill, an instrument of self-destruction. Strange to imagine that a child of nine or ten could conceive of such a thing, but it had been on my mind for some time. I had a phrase for this thing of guaranteed demise. I called it my “certain death formula.” And I had concocted it. Through a bizarre process of childhood alchemy, I had combined ground glass shards, some burnt offerings of cleaning products, a binder from an adhesive substance, and put them into a tiny blown-glass jar, part of a set of German-made miniature vases and bowls gifted to us for our doll house. The glass artifacts were exquisite things, not much bigger than the outer digit of my thumb, and they were fragile. I remember the vase I had selected for this clandestine purpose was black glass with orange-red flame flowers in its design, a fluted edge to the opening, its base broken off to leave a sharp bottom to the stem. This was my most private possession. No one knew of its existence but me, and it needed to be kept safe.

What possessed me, at age ten, to imagine I might need, want, or use such a potion in its violent casing? What scenarios did I conjure to provoke this creation? Were tales of cyanide capsules in the Second World War haunting me? Had I heard a whisper about circumstances in which escape had been impossible, death imminent, and persecution real? Or did I have a more existential fear, a personal sense that life might be intolerable in some way at some moment and that the option for an exit strategy should be available, ready to provide a way out?

I kept the tiny vessel in the box for years. I would open it to be sure it was still there, feel a kind of security at the psychic insurance this provided. I know I had it through my teens, and the box was in my dresser drawer, hidden behind socks, no doubt, for safe-keeping. No one knew about the box and its contents but me, and these extra measures were superfluous. Only bafflement would have been produced had anyone ever found the box, managed its puzzle moves, and discovered the broken glass vase with its burnt crust encasing the mixed material stuffing.

I never put it to the test. Who knows what damage to my esophageal and intestinal tracts might have ensued had I ever swallowed the broken glass vessel. When and where along the way the item vanished I have no idea.

But the box travelled with me into the present. Now its hidden interior contains only the detritus of other moments in my life: a couple of dried sea horses captured for a salt water aquarium my mother and I kept in the summers, an unbroken wishbone, rusted keys to long-vanished locks, a few snippets of mink fur, some miniature hand-carved goblets I once fashioned from the wood of twigs smaller in diameter than my finger, the matches from my boyfriend’s bar mitzvah (he of whom I wrote in “My Holiday Prince”), as well as the table assignment for the after-ceremony luncheon. The last item is a small orange card dispensed by a mechanical fortune telling device. It presumed to describe my personality and the last lines contain the admonition: “Do not expect perfection. You have it not to give.”

The dark cavity of the box has the air of an abandoned vacation house, neglected in a nonchalant way. The items have no tragic quality, they are too insignificant, just things I never bothered to throw away. The deadly vessel is long vanished. Seeing the rest of these items, I register an affectless loss. These are leftover crumbs of the past. Even so, the sight of this faded debris provokes a twinge of betrayal. Sometimes the past does not keep its promises.

Steph,

Thanks for this. We stayed close friends, in my recollection, until the summer of 1964 when a new girl moved into my street. I am so glad you are able to remember these things. I have a photo somewhere of us after my return in summer 1962. I will have to look for it!

Wonderful, sad story. Love the admonition "Do not expect perfection. ... Thank you for having me on your mailing list.