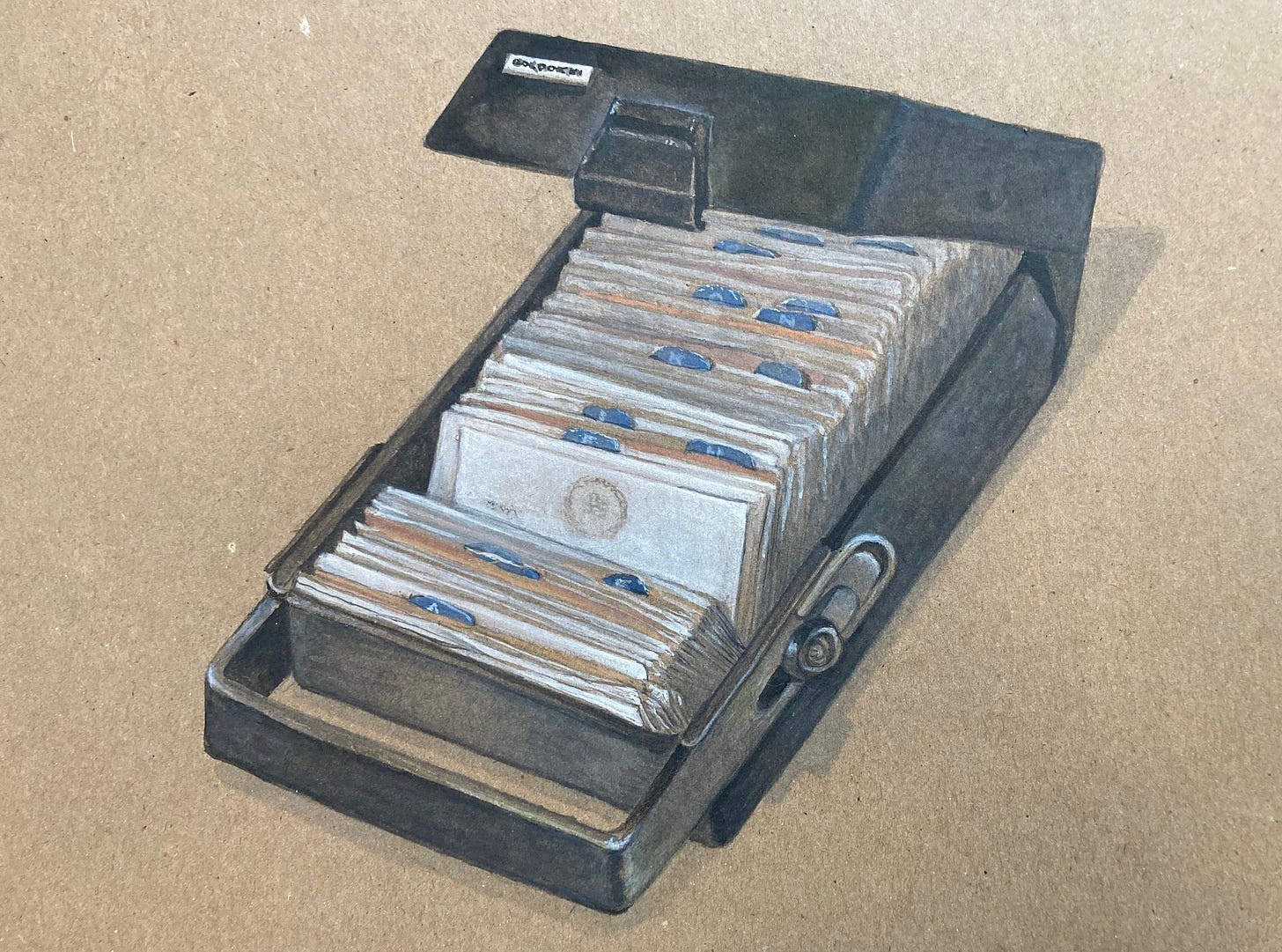

My Rolodex

An immediate clamor arises when I open the black plastic case of my old Rolodex. The tactile satisfaction of clicking the clasp and raising the mold-made lid has a nostalgic feel, but I wonder if I am opening a sealed box whose time-stamped contents will disperse their preserved moments into the atmosphere like pollen from an ancient tomb.

The design is so 1980s. The Rolodex was the ultimate in office accessories before the internet, when networking meant slipping cards into and out of the physical index. The device was user-tested, no doubt, to make every gesture feel like a clear executive decision. More on this in a moment, but first, the noise.

By contrast with my Filofax, whose pages of addresses, contacts, and passwords embodies the quiet of a cemetery through which I wander reflectively, passing through the rows and byways of entries, some crossed out, others faded with age, each a marker of an intimate connection somewhere in time and personal changes, the Rolodex is a site of outward facing social activity. With its physical efficiencies, ability to snap shut discretely, the thing bursts with noisy energy as soon as it is opened. The cards each call out for attention. “Me,” “me,” they shout, each edging their shoulders into view as if to exclaim that “Ray” or “Sarah” or “The Ed Department” or “Mr. Daniel” is striving to be the first to get my response.

Who are all these people? I wonder…. I put aside a stack of miscellany that lies across the case—some misplaced family photographs, a couple of business cards and sticky notes never translated into formal entries in the deck. Amid this miscellany, I find a few engraved bills of foreign currency from before the introduction of the Euro. These are beautiful, multi-colored, and elaborately printed, probably worth next to nothing at this point. I acquired them in the days when I was securing image reproduction rights from museums and libraries located outside of the United States. This was in the late 1980s, before email and online services allowed bank transfer and wire payments, and each permission request required an elaborate exchange. First, you had to find the rights holder for an image, secure the address and the correct office for Rights and Reproductions–which were not always standardized among the various administrative units in museums and libraries. Then, you wrote a letter with an explicit request, preferably in the language of the institution, waited for the reply, and then secured the correct currency for the exchange, returned a signed form with the money, and waited/hoped for the black and white glossy photo of reproduction quality to arrive. These remaining bills are evidence of failed communications, transactions not completed. I lift them out, along with the other odds and ends, so that I can flip through the cards.

The concept of the Rolodex was, according to the Smithsonian Institution, the brainchild of one Arnold Neustadter, who also invented its siblings the Autodex and the Swivodex.[i] Reading the Rolodex as a social technology emphasizes a few of its bolder assumptions. Foremost among these—the idea that one’s contacts would switch in and out with the ease of mechanical parts swapped with the neat click of the punched cards snapping onto their rails. No one had the security of permanent status in this system of interchangeable components. The structure of the apparatus made clear that each acquaintance or contact was only present as long as they were useful. A value assessment was now attached to friendships. Did the individual merit a spot in the slot? If not, too bad, out they went with no trace they had ever been there. The ranks of the Rolodex closed quickly, erasing memory. So clean. So effective.

The very idea of introducing efficiency into social relations marks the transfer of managerial concepts from business into private life. This ideological shift was greatly assisted by the fact that the original Rolodex was a thoroughly modern design object made of tubular metal and molded plastic. Can anything be more iconic of the “modern” office than that shiny metal bent in perfect curves to provide the frame of chairs, tables, lobby and other furnishings or, in this case, to suspend the rolling index at just the right height to let fingers flip through the stack without resistance. The Rolodex is a random access device. Any point of entry is equivalent to another. You don’t have to go through a fixed sequence to find what you are looking for and the alphabetic tabs demarcate the cards into their neatly ordered, self-evident zones. Though my version was the box, not the free-standing object, it functioned with similar efficiency.

Even so, secrets and landmines lurk. My coffin box is more accommodating of loose detritus than the desktop model on the aluminum frame—where every card was always on view. I had purchased the black box version because it was mobile but also private. I would be able to carry it with me, self-contained and self-preserving. From the names and contacts, it seems I must have purchased it in my Harvard fellowship year. I recollect it was an expensive enough acquisition that I debated before buying it. I was in a phase of professionalizing and felt the object would perform a symbolic as well as practical role. It wasn’t meant as a repository of memories, but as an aid to such tasks as creating a mailing list to publicize events and publications. In the late 1980s, everything still happened on paper, with postcard announcements and stuffed envelopes. Lists and crack-and-peel printed labels were part of ramped up systems, not just haphazard or amateur approaches. Everything about a Rolodex said “professionalism” and I aspired to its protocols.

Even the little plastic mold-made sleeves into which the alphabet tabs are inserted flaunt their cultural identity. When, after all, did such transparent sheets and customized forms become so commonplace that they were simply part of the design vocabulary? What are they related to? The breakthrough of flexible celluloid film that permitted cinema technology to emerge—Kodak filed a patent in 1889–was a part of a long series of innovations in what would become the plastics industry. Chemists continued to fool around with other compounds throughout the early 20th century to create products now part of our historic and contemporary vocabulary: Bakelite (attributed to Leo Baekeland, 1907), cellophane (Jacques Brandenberger, 1910), neoprene, polystyrene, vinyl, and nylon were all invented in the early 1930s. All those extensions of plastic innovation, many of which contain “poly” in their names, are complex chemical compounds made from polymers and belong to the large class of materials known as thermoplastics.

Those inconspicuous little alphabetic divider tabs are made of polycarbonate, one of the most popular and versatile transparent plastics. Start tracking the components of these industrial products and immediately find are made of things like BSA (Bisphenol A, whatever that is) and Phosgene (which at room temperature is so poisonous it was used in chemical warfare).[ii] The lifecycles of these compounds have terrifying aspects, and the long term effects of BSA on ecosystems and human health, though slower than the deadly impact of Phosgene, are much studied by environmentalists arguing for tighter regulation.[iii] As to the production of tubular metal and the industrial processes involved in the standard Rolodex—go down the rabbit hole to explore their production and it leads to extraction industries at a global scale with all the damage and effects these incur.

I had no thought of any of this when I purchased the Rolodex and began filling it with entries. I loved the die-cut cards, and the adult sensation of organizing my friends and connections. The device was both sign and instrument of changed status.

Now, the box has a distinctly dead feel, somewhere between a tomb and coffin, in which living encounters are no longer possible. Most of the addresses and phone numbers are obsolete after four decades. Many of the names are people I hardly recognize. If I did a google search on a handful of random figures, would I be able to track the point of intersection between their life trajectory and mine? At some moment, in the complexity of shifting geographies, career pathways, social activities, I connected with X or Y. Now the record of that feels like something recorded in the Sloan Sky Survey, an instant where one complex orbit happened to cross another. But like those crossing points, these social ones are often delusional. The card is a record of an event which, as in the formation of a constellation, appears to map proximity. But, as in many stellar instances, this was merely a projection based on a point of view that made completely unrelated—often distant—objects seem to be close. Over time, the parallax introduced by change and motion separates the stellar objects into their own domains. So, it turns out, I was not really friends with X, who moved in a far more chic and affluent crowd than I did, though I didn’t quite grasp that at the moment I put their contact information onto a card in my file, imagining it gave me access to that person. And Y I encountered once and only once, mistakenly thinking it was the start of something that was immediately and already finished.

The Rolodex is an archive of failures, for the most part, promises unfulfilled, aspirations disappointed, social connections that never came through. Not entirely, of course. Many are cards whose information was so familiar I had no need of the aid to memory. We used to commit phone numbers to mind, know the addresses of our friends, work from the analogue world to its records. Now the order is reversed. “Everything” is stored first and only later connected to the phenomenal world it indexes. The once-deliberate act of collecting information has inverted into a constant and ongoing process against which even constant vigilance is inadequate to deal with the overflowing accumulations. The Rolodex feels like the last stop in an information pilgrimage, the final cultural instrument of deliberate control over social life and connections. And it proved to be an illusion in so many ways.

Still, what surprised me most in opening the dusty black plastic case was the virtual noise, the claims and bids for my attention, voices rising from the cards, a rising murmur of “me” and “me” and “me” that arose from the box as it was opened.

I flipped through the cards, trying again to pinpoint the date at which the Rolodex might have come into my life. Contacts from the Harvard year 1988-89, bled into those in the job at Columbia University. Some cards have phone numbers to which area codes were added later, or changed in the great 415 to 510 shift in the Bay Area. Artists, gallerists, book people, folks who were on museum staffs and in curatorial positions, old contacts in that world all appear. This was my life as I entered New York, still imagining I might find my way as an artist even as the demands of my academic life consumed me more and more. Strange breadcrumbs. In almost all cases, I know something of what occurred with each of these individuals. Many were part of my life for a long time, some even now. But mostly the Rolodex provided a site in which these many individuals were united by the device. They were part of various networks to which I imagined I was connected and a part.

I snapped it shut, unable to bear looking at the unpursued and unfulfilled opportunities it contained. Better to close the lid on all that, muffle the sounds with darkness, shut away that crowd into a dark and airless fate, let that era go. Some things are past, their revival a useless expenditure of intellectual and emotional energy.

Nothing lasts. But things don’t last in very different ways. The illusions of a social network that the Rolodex configured dissolved, leaving only clutter and empty clamor. But even more, the delusions/illusions of professionalization and managerial control evaporated along with my (brief) adherence to the values that sustained them.

[i] https://www.si.edu/newsdesk/snapshot/still-rolling-around

[ii] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phosgene

[iii] https://www.niehs.nih.gov/health/topics/agents/sya-bpa/index.cf

Interestingly, they're still widely available and evidently sold by the thousands. I still keep piles of note cards in a kitchen drawer.