Keeping track of our contacts is easy in the age of cell phones and personal devices. Every new entry is neatly structured into well-defined fields with admirable efficiency: cell, home, work phone, email, and so on. When the information is updated, the old information is immediately removed from view. No hint of history attaches to the way these entries look or behave. They might as well all have been made on the same day, or transferred wholesale, as many were, from an older phone into a new one. The contacts live in the present. Even if some entries are neglected or obsolete, their uniform appearance betrays nothing about their past.

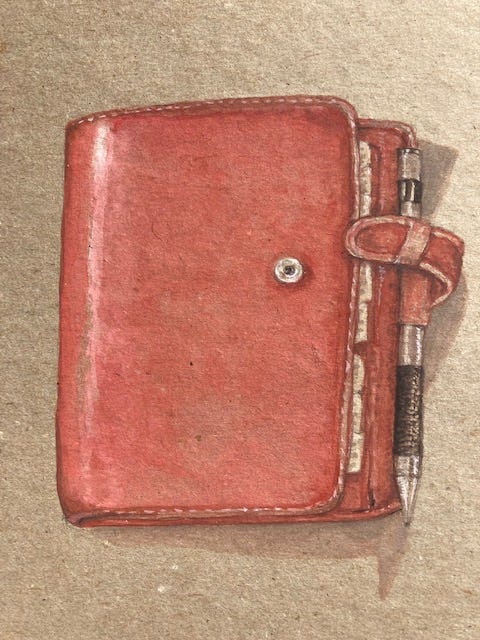

Filofax, watercolor on cardboard, by the author.

By contrast, the paper pages of my address book are worn with use. The edges have the softness of old clothes. The paper-sharp sheets have curled through frequent turning in the search for a phone number, address—or a password filed alphabetically by organization or site. Even sources of online information live on paper here, in the quaint but functional format, and it is likely they will outlive the digital versions. The small book, shaped to the hand, predates electronic record keeping, dating from a time when pen and paper were the primary mode of record keeping. The leather spine is also aged, showing signs of wear from frequent touch, buffed shiny patches and scuff-marks from rubbing against items in a purse or backpack. But the artifact betrays other features of its history—and mine.

The address section of my organizer was once the only way I could find my friends and colleagues. The tab dividers grouped them by the letters of their last names, making random neighbors of individuals from otherwise disparate parts of my life. School friends and cousins who never met are right next to each other, far from people they might know. Skimming through the entries on the way to retrieve some specific bit of information, my eyes move over the handwritten landscape. Here is an entry written when the page was fresh, allocated three entire lines for the full name and complete address. Here another in the same pen, obviously made when an older book was being copied selectively but systematically. Then, in another entry, the writing changes into a small, cramped hand, for information quickly noted. Further on, in yet another pen, a crossed-out phone number, rewritten zip code, and altered address record the ongoing connection to someone whose life remained linked to my own.

The pages are dense with interlinear additions and deletions. Nothing has been removed. No erasures and no white-out fluid reclaimed any of the real estate on these pages. But the open space has slowly disappeared with the increasing density of occupants. Echoing the in-fill of development in an urban block, the pages record more than the information of addresses and phone numbers. Like those varied house fronts and store windows, each is linked to a moment in time when that particular entry made its appearance among its neighbors, taking up residence in the decreasing inventory of empty spots. Some of these sites seem closed down, as if their curtains were drawn or their lights have gone out. Some are so overwritten they seem slated for demolition. Others remain pristine, crisp and fresh as when first entered, whether they are live links or not.

The history of my social life is marked and visible in the rich details. Some names are almost unrecognizable, not because of the handwriting, but because the association has faded completely. Who were the “Kaplans” or “Kramers” so familiar I did not even note their first names? I cannot recall at all. But in stark contrast, on the same “K” page, sits a lone name, “Tally,” stripped of the surname that warranted the location. A friend and colleague I knew for a decade. No other Tally existed. Her family name was superfluous because I knew to search for her near those seemingly mysterious Kaplans. Now she’s gone. One of the vanished. Dead, deceased, passed on. State it how you wish, death remains a stark reality. No euphemism softens its irrevocable finality.

The deeper connections are not gone, only shifted to another phase, one in which commemoration remains vital. Switching to the clean blank slate of a new book would write out of existence the last points of contact that remain. So I move among the entries, noting who has gone and who remains, and in the process, I feel their presences. They are not ghosts, not longing spirits, not anxious souls bidding for attention or needy in their changed state. They are points in the constellation of contacts that locates me within my own configured life. My identity is defined by its relation to others, so I maintain their places.

The address book serves as my own private cemetery, even as it still works as an inventory of the living. I cannot bear to remove the names of the dead from the pages. Instead, I visit their entries. Beloved G., gone without warning. I land on his name, see his successive addresses. I visited each and knew them well. The idea of removing these traces is too painful to contemplate. The entries are not scars, not wounds, though a twinge accompanies my encounters with these memorial tributes. I like to see them, to pause. I recall the beloved features. G.’s dark spiked hair, his black eyes, lean face and wry smile. I am able for a moment to be immersed in recollected details, reminded of his predilection for fine cotton shirts in small check patterns fitted to his elegant frame. The addresses track his movements from the East Coast to the Bay Area, his work in a start-up, rapid rise to sudden success. One address is for an apartment in the Mission, with its deep red couch, much-used piano, and persistent wall of boxes that never got unpacked, just moved from one location after another. Scribbled in hastily, the address of his parents, email for his sister, evidence of the frantic search for contact information in the wake of his untimely passing. These traces of tragedy had their own time frame attached to them. Now they are an isolated island in the memory streams, disconnected from any ongoing life story.

Many entries trigger intense chains of association. My father, my brother, and my brother’s surviving wife are all clustered on the same page. They are major monuments among the graveyard of addresses. The letters that make up “Dad” or “Dave” have the gravitas of inscriptions in marble or granite. Their identity has a permanence. I pause each time I go by, not wanting to be disrespectful to their memory. In the midst of utilitarian activity, the prosaic search and mundane tasks, I take a moment, brief and fleeting, and pause. In those few seconds, I have spent a moment with them. They are not gone. They remain in their spots. Some, like my father, still hold pride of place. They were the first in the entries on their pages, and stand at the head of long lists that accumulated over time.

In some cases, cross-outs and additions also chart increasing intimacy. A formal entry, full name and a phone number, becomes the node to which new information attached. A home phone number appears next to the institutional one, then a cell. Access has become more immediate, part of a pattern of frequent and then less formal social connections. Often the institutional number is crossed out, a new area code appears, and another home address is added. These are the active areas of update and renewal, sites where the contacts stay alive, at least for awhile. And then upkeep lapses, the weeds grow over the spot. Some entries have been re-located to another page when a change in the address doesn’t fit near an original hemmed in by new additions. Without space for new information, the displaced soul has to move to a new spot sometimes far from their original prime location.

Some sit like silent headstones, the fixed, static records of once-regular exchange. How long since that number was called? Would a living voice respond? Some numbers are so old they were once dialed, accessed through an electro-mechanical device. A vanished era, not visible in the actual code of the phone number, but recollected as body knowledge familiar with the sound of the dial pulled to the right by the index finger, then let go to spin back to its start position. Bakelite receivers, black and dull, held to the phone or pinched by the neck, were replaced by phones of many colors. Princess phones in red, yellow, white, green with their square keypads, so stylish, so contemporary, and now so obsolete. Some of these numbers predated answering machines. These were at first a rude intrusion into social life around which the decorum had to be defined. Was it polite to leave a message? What kind of message? They became instruments for the shy, the cowardly, or the obnoxious caller to say things they lacked the courage to say directly. They left no trace, only a ghostly memory of their operation.

The address book indicates these technological shifts only obliquely. In a few cases the code for the exchange still spells out some older version of the directory—where “Locust” or “Walnut” was abbreviated as “LO” or “WA” in the prefix of the number. The massive shift to cell connections is marked by the peculiar area codes that had no logic to them. The geographical identity of now-famous ones like “415” or “212”—impossible to acquire now, so overloaded and exhausted were their circuits—has been replaced. A random set of digits, “676” or “357” serves in what is clearly merely a digital universe requiring a unique address within a vast universe of strings. They call nothing forth, no mnemonic of a city or rural district, no cluster of people into a community, or point that can be tracked to a map. Now the numbers are attached to a device, not a place, and provide access to a personal unit, mobile in space, available for surveillance operations as much as communication.

So, I wander through these neighborhoods, taking in the view. Generally I am in search of something in particular, but then become distracted by a trigger to recollection. A few transient entries on post-its remain attached, like squatters temporarily camped over an existing site. They came for a moment, and never left. Occasionally, one is blindsided by the startling reminders of aborted relationships, failed romances, broken friendships, betrayals. Some notes were provisional, as if the entry were on probation, and failed. Turn away, quickly, and move on. Why linger in the presence of these reminders? Some are undug graves, merely marked out with string and stakes. Others are unfilled, open, and unfinished.

Many moods are expressed in the writing, the variety of upright stance, angle of slant, or generous open curves in the letters. A sharp thin line inscription in a super-fine pen tilts like headstone listing in the settling earth. Another in a heavy dark pen holds its place, tight and bold in the field. Another hangs on, but barely, having been set too deep or tried to rise too high, while yet another threatens to disappear entirely, fading into pale lack of distinction from the ground. One or two entries are bracketed by a long line drawn along them in the margins, as clearly staked out as if surrounded by low iron fencing. Others are caged in minor boundaries, sequestered just enough to stand apart. And then there are the tiny plots, the small entries, fitted in-between as if to demonstrate the infinite capacity of graphic space to subdivide into ever-smaller portions. Each entry stakes its claim on individual terms—cramped, strident, modest, or polite—as if merely stating an identity or, by contrast, flaunting it with elaborate engraving. They are all undecorated, so the lettering has to serve to distinguish the names from one another.

In a few places, additional pages have been inserted. Some neighborhoods (the S’s and T’s, for instance) were over-populated, and so new territory was added. These are startling in their freshness, as free of tangled growth and intertwined remarks as any newly laid sod. They have not had time to acquire the patina of age, nor to contain information that recedes towards a horizon of recollection rather than a field of action. On these bright sheets, new entries occupy the freshly broken ground. These clean texts seem lonelier than the entries that crowd the older pages, as if they are too far from anyone else in the open space around them. Sometimes a half a page or more remains untouched, as if waiting for subdivision to allocate plots for future occupants. And on the back pages of each section, before the alphabetic tab that marks a new aisle in the organizer’s alphabetic system, the outcasts. Here newspaper subscription passwords and information for accessing the back-end of a once-used web-site lie side by side in the glamour-less margins at edges of the property. No full-scale entries with people’s names or addresses are there, only the dregs of information for the most incidental of contacts. These are the zones of neglect near the boundaries beyond which nothing registers. The most marginal are the entries scribbled on the tab separators themselves, apparently unworthy of a place in the sanctified ground among regular inhabitants.

The top margins and edges are reserved for password information. Often only a short identifying acronym, informal and unceremonious, identifies the business or institution with which the often meaningless sequence is associated. These encode a history. At first, the pet-names, simple, and direct, were adequate. Another memorial is present in the succession of Pushkin, Fluffy, Fido, Ticket, Toppsy, and Pik-Pak rubrics. Rising challenges to security registers there. The names become saturated with Spec1a! char@cter$ and numbers, no longer able to serve a secure purpose simply with a string of humble letters. Even in their afterlife, the stature of these loyal guardians drops when they can no longer protect the bank accounts and online services of their human companions. The slow corruption of terms of endearment distorts their appearance, as they become less and less recognizable in order to be ever-more secure.

Many names of the living remain, though they, too, are frequently no longer active. Some are like luggage tags for a trip taken years ago, kept just in case some follow-up contact is required. Once in awhile, someone else’s hand appears, clearly the outcome of a spontaneous moment of connection, “Here, let me write it myself.” The book, handed over, was inscribed in unfamiliar lettering. Noted quickly, and never used, many of these entries are as inert as those gravesites with long-faded flowers. Other connections were never alive, but like plastic bouquets were quickly drained of color, turning dull and sad.

Each year, in the many rows of tiny entries, more and more are of the dead. But the graveyard of paper and ink has its own limitations and sensory impoverishment. In the electronic records of emails and voice mails, other traces remain, different in quality and kind, but registering with the same impact. On an old answering tape, my father’s voice comes to me from a remote moment of past connection to record a communication whose very banality makes it poignant. No need to remark on an ephemeral message that registered a passing thought, shared reference, when exchange was so casual, so frequent. Don’t bother to return the call, he says, recognizing that the schedules of our days might not be easily synchronized. And now, no possibility. The transient immediacy of speech is trapped, paradoxically, in the permanent recording, able to be repeated endlessly, as if by playing the short message, contact might be recovered.

Each medium has its memory forms, traces suspended between the irrecoverable and the lost. Many are dead links, broken through neglect or disinterest. Others wait like landmines in the field of unsuspected recollection, waiting to trigger a sudden explosion of emotion, hot rush of longing, nostalgia, loss. The records that preserve the dead serve a deeply human purpose. Not sentimental, but memorial, they are an active inventory, to be visited in these private cemeteries, where they occupy an intimate resting place in the long journey of shared lives.

I am planning to make all of my personal commentaries have an image I paint that accompanies them. I loved painting this. So glad you enjoyed looking at it.

Your analysis brings out so much the depth and range of emotions tied into this tiny everyday object ... It reminds me of my sister's experience with voicemail --- for years, she kept alive a number of messages left by departed family and friends. Every few weeks or so, the system would ask her to verify whether she wanted to delete the messages, and to keep them recorded, she had to listen to every message and indicate that yes, she wanted to keep it. She did this for years, as a way of hearing the lost ones' voices. The process only stopped when she moved and couldn't keep the same phone number. She was able to save the messages on a device, but the embedded ritual of recollection was lost.