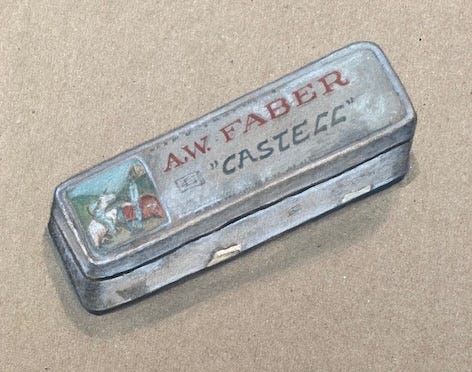

My Pencil Box

Battered with age and wear, this tin pencil box was given to me new about four decades ago by a then-roommate working a brief stint as an employee at an art supply store in Berkeley. She came home one day with several of these boxes, their stencil-painted surfaces and rounded corners already reminiscent of another era. They were part of an abandoned inventory, deemed useless when a cache of them was discovered on a neglected shelf. Though designed to hold pencils, they were empty of their original contents. I was happy to have a container that fit my beloved Turquoise blues, then, as now, my drawing pencils of choice. The fact that the retro design of the box was out of synch with the 1980s’ fashion sensibility and modes of manufacture didn’t trouble me.

Gouache and watercolor on board, by JD.

Think about the humble pencil for a moment and what a miracle of modern industrial production it is.[1] After all, though graphite occurs naturally, and can be used to make marks, it has to be ground into a powder and mixed with clay and water before it can be turned into those miraculously thin rods that make what are generically identified as “pencil leads.” Graphite sticks (likely) appeared in their bare form in the 17th century, when metal tools such as silverpoint were still being used as drawing implements. The manufacture of the far less precious–and more versatile–graphite sticks use soon followed. Surveyors, draftsmen, printers, and anyone with a task requiring a portable writing instrument could carry one in their pocket. Imagine. The list of people who ventured into pencil production is illustrious and includes Henry David Thoreau as well as Henry Bessemer (an innovator in steel manufacture). The challenge was to figure out how to get the graphite into a usable shape by cutting or casting so it could be encased in wood that held either a slimly cut stick or a finely cast rod. The move from the original design concept into mass production occurred in the 19th century.

Nowadays, cedar is apparently the wood of choice for making the grooved slats into which the graphite core is placed before the two sides are glued together. The finished sticks are painted, capped with a tiny tin end (known as a “ferrule”) which is pinched and ribbed, sometimes topped off with an eraser. Then the pencil is stamped with the manufacturer’s brand, a number indicating hardness, and sometimes a tiny logo or other marking. Mine are Eagle brand, with an elongated “moderne” bird stamped in silver on one side of the hexagonal shape.

Like so many familiar objects, the pencil is something I could never make myself, dependent as it is on machines and processes so specialized that the amount of engineering that goes into the process is nearly unimaginable. At least, this is what I learn from watching a highly-produced and informative video on YouTube where pencil production is reduced to a seven-minute smoothly running operation in which no glitches, errors, or flaws intervene between the arrival of neatly milled cedar planks to a factory and the sight of the perfect pencils—glued, dipped, stamped, and finished—rolling off the end of the assembly line.[2] The rhetoric of the video is one of effortless efficiency, and no pause for reflection on the state of cedar harvesting or the extraction industries that mine and refine graphite show up in its smoothly edited minutes.

Somewhat curious about graphite itself, I do a superficial Google search and find that graphite is a form of carbon, the result of a sedimentary activity in which deposits of plant and animal remains are compressed into a layered, flaky substance. If you begin to read the geological literature, the vocabulary gets much richer very quickly and mentions of “sublithospheric sources” or “decarbonation reactions of carbonate-bearing lithologies” show up.[3] Graphite gets used for all kinds of things—lubrication (graphite powder in your locks and on rails to keep trains from screeching), polish, paint, and batteries. Extraction at scale has ecological consequences, but Neolithic people already accessed it for decorative purposes in the 4th millennium BCE.

But before we get lost down that rabbit hole, let’s go back to pencils and the arrival of this tin container into my possession. The box is linked to a time of intersecting lives with roommates in a large, unheated warehouse in Oakland where I lived for seven years with a shifting cast of characters in that incidental intimacy that cohabitation produces. For better or worse, one knows much about roommates, the way one knows that a mouse is in the house by the remains of their meals and activities. Traces of actions, food habits, social patterns and behaviors were all evident in the way things came and went from the refrigerator, were left in the sink, or hung to dry in the bathroom. You had to choose to be discrete, only engage with those topics offered, not the information that came from that oblique surveillance of daily interaction in a shared space. We knew too much, sometimes, about the boyfriends, the parents, the arrangements being made on a still-tethered landline, our only phone. One particular roommate had incredible natural collections, and I always hoped she would assemble a fantastical dinosaur skeleton from the boxes of bones and feathers that had come from animals kept by her parents on property in the Berkeley hills, or found in desert hikes and mountain meanderings.

I had few possessions in those years, having been engaged in travels and an itinerant existence, so the pencil box, though hardly an object of significant monetary value, was still precious in all the ways that thoughtful gifts spontaneously given can be. Pencils were central to my artistic practice, and my skills at drawing had grown directly in relation to my knowledge of the properties of the B, F, and H designations that divide their leads into soft, hard, and in-between. These rubrics are only the most superficial aspect of how one pencil differs from another. A 6H pencil holds a point so sharp it can pierce the skin while the marks it makes can be nearly invisible to the naked eye. To create a consistent, always light, tonal value with a super-hard pencil, patience and persistent stroking are required, and even then, the hatch marks refuse to blend, though the result can be a soft glow that is nearly sublime. By contrast, in the B range, the soft graphite leaves a shiny, almost greasy trail, and though the depth of tone in dark shadows creates absorption, a black hole on the surface, it can also make murky smears that lose all articulation. The difference between the color of one graphite pencil and another also becomes conspicuous, with the cooler tones in the hard pencils difficult to blend into the warm depth of softer ones. These are subtleties that only become apparent on prolonged acquaintance, just as it takes time before one notices the habits of thrift in that roommate who preserves a morning teabag for an afternoon cup. Knowledge takes time in any domain.

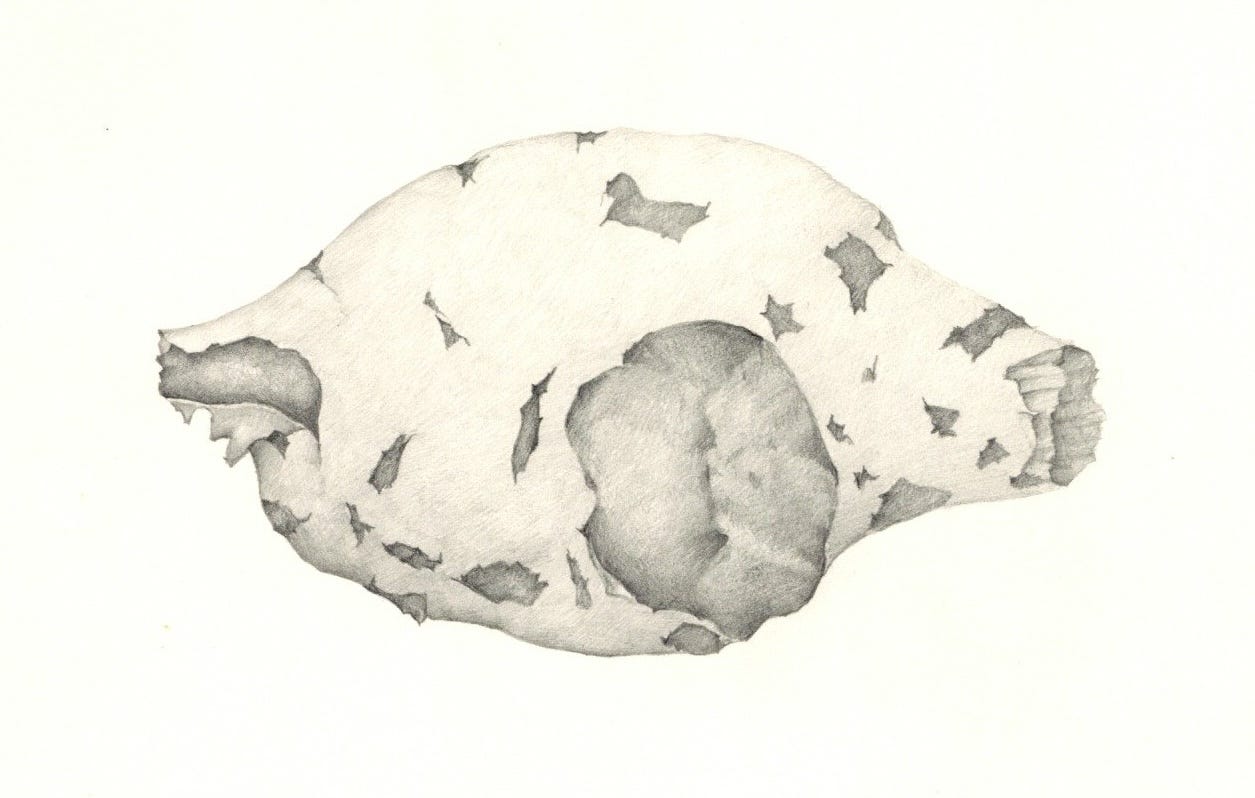

Pencil drawing, made with graphite, 1971-72, by JD.

Pencils and paper had been the core tools of my visual art education. They were affordable, unlike the materials of video or photography, which required equipment, film, developer, cameras and other investments beyond my means. More importantly, pencils had a tactile directness and the way in which I worked with them was physically intimate. I drew at the scale at which I wanted to think, making images meant to be seen up close, appreciated with the same attention with which they were made. These early drawings were studies of organic matter, dirt, fragments of leaves, minutiae in a state of decay. I was learning from my observations. At first I saw the forms in their infinite variety and specificity. But soon I began to understand that these organic objects, or entities as I called them, were evidence of highly complex processes. They were embedded in ongoing activities of transformation. Through these studies I became attuned to the animate character of the natural world and, slowly, by extension, the larger systems at work in the universe, pursuits that expanded over time.

So, the humble pencils were an instrument of revelation, intellectual insight, and unlimited possibility for production as well as understanding. The F pencil, that enigmatic one that belonged to neither the hard H’s nor soft B’s, became a great favorite, capable of a strong dark mark but also able to produce smooth tones and patterns that followed the ripples of bark or spots of lichen or delicate network of mildew.

The history of Faber who produced the tin box_and its “Castell” line_begins with a German family. Kasper Faber’s first factory as founded in the 18th century. According to the Wiki account the business began with pencil production in Germany, expanded operations by establishing factories in Europe and the United States in the mid-to-late 19th century. Then, when one of the female scions of this long line married Count Faber in 1898, the couple decided to create the “jousting knight” motif that appears on my metal pencil box. Appropriately enough, the two combatants attack each other with pencils from astride their well-dressed steeds. This branding campaign consolidated the “Faber-Castell” line in the true spirit of turn-of-the-19th-20th-century medieval revivalist aesthetics that had inspired architecture, book illustration, stained glass, and other arts and crafts movements in the period. More details on the history of the company, its products, family traditions, fate across wars and political events expand this story, but none of that was part of what was evident on initial encounter with the box. When given to me, around 1979 or 1980, no Wiki was available and no one would have been likely to track this history of Faber-Castell just for the fun of it—and how would you have done that anyway? What sources existed for attending to the history of office supplies, art supplies, or even major companies without resorting to highly specialized libraries and archives?

The kitsch-y appeal of the jousting knights, the well-made hinges and neatly matched top and bottom of the box, all retain their satisfying character. This was a treasure, a compact and reliable container in which to carry pencils across space and time. I did not have the green painted pencils of the Count Faber’s military regiment in my box, but instead, my Turquoise blues, a handful of which remain in my possession, still faithful instruments for graphic work, alongside a cohort of more recent recruits and late arrivals.

As to drawing, it has been central to my explorations of much more than the pictorial representation of the natural world. Though that is where I began, the work led to investigations of the processes and forces that underpin the animate workings of the universe. Seriously. The study of organic debris, small bits of dirt and dried matter, provided an insight that proved inexhaustible—the study of how form comes into being as configured energy. This includes the ways in which the non-linear and stochastic workings of systems at all scales can be understood. When the Faber-Castell box appeared in my life, these investigations were well underway in my studies of entities and processes.

The box remains, a quasi-static object whose persistence across time does not depend on me except in the incidental act of custodianship. Meanwhile the constantly emerging drawing practice stays active, persistent, but in flux, always unfolding. The responsive capacities of graphite led me to an understanding of the animate character of the physical world. The relation between sight and touch, seeing and knowing through the integration of hand and eye, developed as the pencils were consumed in the active exploration of knowledge through touch.

[1] Henry Petrowski devoted an entire book to the pencil’s history. The Pencil: A History of Design and Circumstance. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 1990.

[2] Search How Pencils are Made on YouTube.

[3] https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00126-013-0489-9

Wow! When did you get it?

I too have the same tin. But I keep a black plastic centipede inside of it… for some reason.