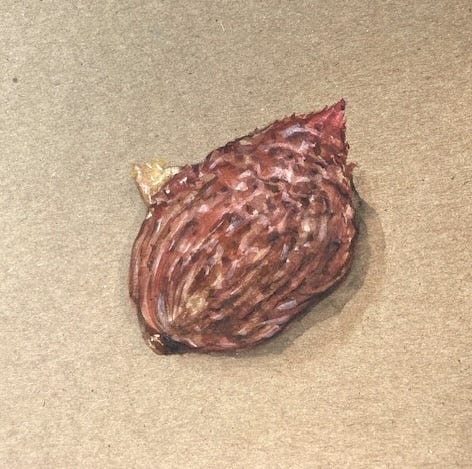

My Peach Pit

Gouache and watercolor on board, JD, 2025.

Once in a summer, more if you are lucky, you eat a peach that is the quintessence of the season. The fruit is redolent with perfume, the flesh sweet as juice, firm but yielding, the flesh described by lovers of all kinds. The pit comes free without resistance, dark, hard, and with just a shred of the fruit still attached, shining with inexhaustible succulence. This pit is from my such singular peach of this summer, the most extraordinary and exemplary one so far. And now, some days after eating, I cannot conjure the taste, only recall that it was incredible. Sensation fades, like physical pain, which is remembered but cannot be revived as direct experience even if its emotional tone can be recaptured. Where is all of this information stored, so specific that one piece of fruit occupies its own entire file in memory out of all the moment to moment experiences of every day? How can we afford such luxuries of mind, thought, cognition, and sensation?

But the peach, like so many objects I encounter, is not an autonomous entity, simply a freely circulating thing. If I pause for a moment to imagine what is involved in the appearance of that peach into my hands, the complexity of it staggers the mind. And this was a Farmers’ Market peach, about as direct in its arrival from farm to kitchen as can be managed short of having a tree in the yard. It has its own elaborate history of cultivation, production, shipping, distribution, and consumption with all of the complexities of labor, ecological impact, and costs.

When I moved to California in 1970, many of its more exotic fruits and vegetables were things with which I had had scant acquaintance in my childhood. One friend of mine whose family were slightly more stylish and “contemporary” than mine, regularly had tiny slices of avocado in their evening salad. I was unsure how I felt about the slimy green substance, not having been properly introduced. We never had it at home, my mother having declared it “soapy,” though I am not sure if she meant the texture or the flavor. In the first months after my Berkeley arrival, one of my housemates was a slim, hyperactive, rich girl (or so we thought because she came from Greenwich) who swore by her daily consumption of an entire avocado. This seemed as extravagant to me as her carefully managed wardrobe and elaborately casual salon hair. The pits from her avocados littered the window sills, stuck through with toothpicks to suspend them in jars of water where they sometimes sprouted but never grew large enough to plant. Like many of us in that house and situation, she had no nurturing instincts or impulses though she kept to the ritual of giving the avocado pits a chance at survival.

Even given relative abundance, or availability, the avocado was a slowly acquired taste, to which guacamole served as the on-ramp to appreciation. By contrast, the spiny leaves of artichokes posed a significant problem. We had once, in my Philadelphia life, given them a try. My mother, who was more adventurous than experienced, had read up on the way to grasp the leaves between front teeth and scrape the steamed flesh free from the fibers. The experiment was a failure, and none of us managed enough of get the flavor of the thing, so the consumption of these exotic-seeming thistles had to wait.

Again it was the context of the group house that brought me into better understanding of how to appreciate the subtle leaves. The household was mainly composed of young male Berkeley students, all good sorts but inclined to minor hazing by age and the disposition of the times. A few of them watched me pull the leaves, one after another from my first artichoke, until I reached the core where the spines were concentrated above the heart. “No, no! Stop!” they warned me, saying that that part of the plant was toxic and would make me sick. “Let us take care of it!” they offered, scraping away the small leaves and helping themselves to the rest of the choke. I was baffled as to how they had immunity to the poisons that lurked. Later, when I wrote the draft of a musical, it contained, not surprisingly, a tune titled “Too Bad that Boys Are Bad.”

That period was a time of many new tastes–like real peanut butter and ground coffee–and included the incredible sweetness of California strawberries barely hours from the fields, and apricots that peeled from their tight round pits, and the unbelievable sensation of being able to open the window to my small bedroom and pull a lemon fresh from a tree. California’s bounty wasn’t limited to fruits and vegetables, and my daily meals of zucchini, peppers, beans and broccoli were all regular reminders of the difference between the seasonal limitations of the East Coast and the year-long availability of the West. We had a fruit and vegetable vendor who used to come through our Philadelphia neighborhood crying out his name and advertising his wares. The produce came from a truck farm in New Jersey and the owner sold it using a metal scale hung in the open back door of the vehicle, its deep pan swinging on a long chain between each sale. We listened for his arrival every Saturday during the seasons when he came, aware of the difference between his produce and that which was packaged in paper and plastic in the supermarket, far from its source. The farmer became so successful that he opened a store in Center City, which grew to a major institution, much appreciated by the community. But his stock was still limited to what could be grown in the mid-Atlantic zone. I don’t think we ever had fresh figs, or citrus, though melons, stone fruit, and berries abounded in the summer, apples in the fall.

The pleasures of real food never carried any taboo. I couldn’t have imagined thinking it decadent to have a sliced ripe tomato or cantaloupe for a meal. But when I developed a taste for mangoes, the fruit crossed a line with my mother, who had always had to struggle to shake off the inhibitions of her Calvinist upbringing. One summer, when I was in my twenties and affluent enough to afford a bit of discretionary purchasing, I carried half a dozen ripe mangoes to a family vacation. They were all in full ripeness. Their perfume permeated the air long before they were sliced open to reveal that shining orange fruit, dripping with flavor. My mother took one whiff, one bite, and swore off immediately like someone tasting original sin. She refused to eat any more and turned away to avoid temptation.

The prohibition did not pass to me, but I also never forgot the incident any more than I ever let go of the memory of having my first artichoke heart stolen by mischievously wicked roommates. Though I don’t put fruit into a taboo category, I also cannot avoid the connections between what I eat and the connections between politics and food production at this moment in time, particularly in my home state of California. The flavor of summer prevails, but inflected with the taste of knowledge.

Wonderful recollections. We, too, had the milk delivered and found the bottles with separated cream on the top. The store the vendor set up was on 20th Street, near The General Store. Not sure how long it lasted. And do you remember the avocado in your salad?

Funny, I don't remember a fruit and vegetable vender on Spruce Street right around the corner from you. I do remember having milk delivered to the doorstep and how disgusted I was with the layer of heavy cream at the top. In Chestertown, Maryland at my grandparents' summer house, I remember my grandmother driving to the farm a mile or so down the road where we bought juicy fat beefsteak tomatoes and warm raw milk just brought to us from the milk house. Once back home my grandmother would pasteurize this milk using a special electric pasteurizer that left the kitchen steamy, hot and, to me, smelly. I never wanted to drink that milk.