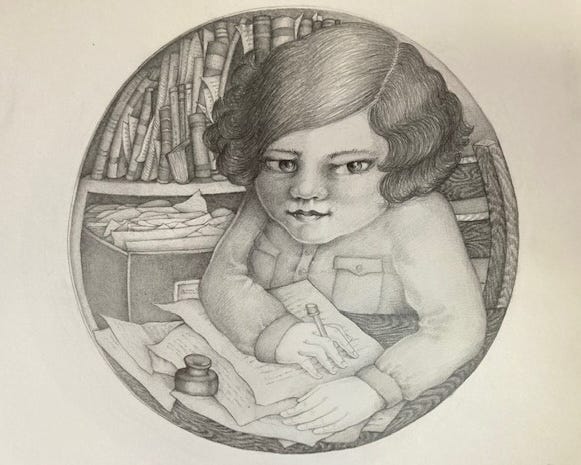

Graphite pencil drawing by the author, 1974.

“Oh Oh,” the character in this drawing, was an obvious avatar of myself, a persona created to express and explore aspects of my existence in the fantastically dense language natural to me at the time. The first paragraph of this manuscript reads:

“Each to his own is the bubbledome, reflex reaction and catalogue comb. We direct and we ponder controls by the board, panel, participate, errant display is the wander to lust to consider to climb in continue. Oh Oh as well was one such in the globe, holding the shaft stick of shift by the knob, it was wooden, and play. She pretends to direct her avoidance, or versa–skill still requires an admissible craft to be airborne.”

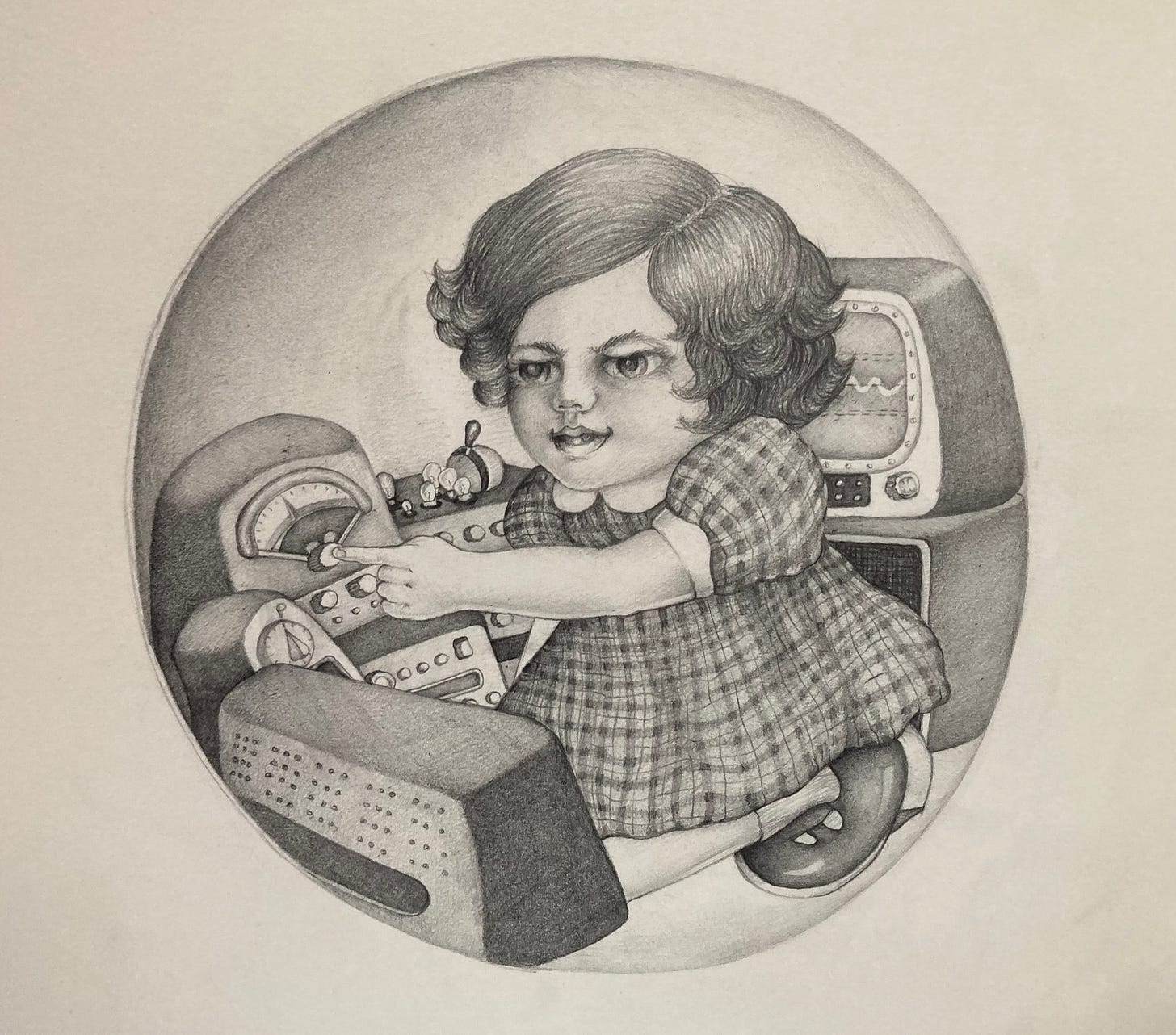

What was I thinking? The elaborate puns, double-entendres, and associative meanings in these clotted sentences are striking. So are the concepts. Little OhOh, labeled “a post-non-Euclidian child,” was part human and also, part algorithmic function, combing the catalogue of options to determine her actions. The “controls” were externalized, but metaphoric expressions of internal processes. The sheer emphasis on the complexity of decision making processes—she “pretends to direct her avoidance, or versa” implies a high-level logic not governed by processing gates or binary options, but layered with the capacity to pretend, to dissemble, even to deceive herself.

Graphite pencil drawing by the author, 1974.

The conceit of the work is that Oh Oh lives in a clear bubble, a spherical dome, the actions of which are willed by her thoughts. But she is hardly a creature of free will or mechanistic determinism. The many vicissitudes of circumstance play their role, as per another paragraph on the opening page:

“Oh Oh, Oh Oh, riding high, crest upon the crestlake sky, how prettily you force your honor bounding by the crass belt banner, yours unfurled you mire within you waiting the grim spectator version of chance to uncurl it.” What the referents are for these evocative phrases is not always clear to me, but “bounding by the crass belt banner” must be describing some habit of repressive dress or behavioral codes that kept her willful energies in check. The “chance to uncurl” is the desired outcome, and Oh Oh waits for the opportunity, hoping for a shift in what—circumstances? Permission?

The text is as dense throughout as those opening paragraphs. The manuscript stretches for more than a hundred and twenty pages, narrating the events of my actual life in the summer and fall of 1973 but in that coded prose. Alternating between “in” chapters focused on Oh Oh’s interior life and “out” chapters in which she encounters the others who formed the real people/characters in my experience in those months, the prose never shifts from this dense associative style. For instance, in the chapter where I returned to the group house where I had lived several years hoping to crash for a night while I found a place, arrival is described this way:

“Oh Oh, Oh Oh, up to the door of that infamous house where she’d lived time before. Crept under the hanging decrepitude vines, all tangled in adamant growth, all entwined, all in glorious, fecund, fulfilled unchecked cling, bogged her bubbledome belly down light on the stair. Who was there? Was she let in and welcome where once she strode free? Would the untipped balance fall heavy now heavy when with light humble step she came needing a place pacific to house and consider?”

This goes on. The entire autobiographical text is written in this rhythmic verse, while the story unwinds an account of real events. I had spent the winter months of early 1973 in Connecticut, with my boyfriend, living in a barely heated summer cottage on a lake, painting, drawing, making one-of-a-kind books, and occasionally going to New York city to try to find work as an illustrator. I was so young and naïve that at least one editor in a publishing house asked me if I knew how to get back to the subway…

I had returned to the Bay Area to complete my diploma requirements at the California College of Arts and Crafts and remained. I found a room in a North Berkeley basement apartment with two roommates. I listened to the Watergate hearings and prepared for an exhibit an acquaintance from school had helped to arrange in November at the California School of Professional Psychology. Various individuals came and went through my life during those months, and all show up in Oh Oh, the subtitle of which was “Among Them.”

I had published my first artist’s book in 1972, Dark the Bat-Elf, and sent a copy to City Lights in wild expectation of response. Amazingly, it had come in the form of correspondence from a young writer in the circle around the Surrealist poet, Philip Lamantia. They were reading my work! They wanted to know who I was, to meet me. I was over the moon. The stories of connecting with these figures, Davidé, his friends, and the reclusive Lamantia are told here in coded verse. So are the accounts of an affair with a former teacher, connections with a painter friend, her lovers, and a lonesome young man of their acquaintance I named “the Stray,” with whom I staged a “Foiled Seduction” scene described in the penultimate chapter. (He never showed up and I drank several of the bottles of beer I had bought for our rendezvous.)

After the exhibit in November I left the Bay Area again and reconnected with my boyfriend. He went out to California in January, 1974, and found a place for us to live in Felton, off Route 9. He moved there to play music with his brother in aspiration of making a living in clubs. He was a gentle soul, a kind vegetarian with thick blonde hair to his shoulders in the style of the day who wore belts woven from wool to avoid any leather. We lived in a small cottage on the property of an organic farm. He practiced at his Yamaha keyboard and I used the dark back room for a studio where I sat drawing and writing my densely clotted prose texts. The depth of my interiority was so extreme that I wonder how I ever surfaced from it. Financial circumstances forced me to get a job as a waitress and it was the best thing that could have happened. Shyness became a luxury I could not afford, even if the deep space of interior life continued to expand. The prose style that was symptomatic of its existence lasted well into 1975 and I produced several books and manuscripts written this way.

Typed on Eaton’s Corrasable Bond, the Oh Oh manuscript is now buckled and wrinkled, dry and fragile. The neo-logism, obviously, combines “correction” and “erasable” in a rather salubrious way. The marketing people had succeeded. The paper stock was a patented invention, 25% rag content, with a special surface that made it easy to erase so that “Errors disappear like magic” according to the the manufacturer, Eaton’s, a division of the company Textron.[1] That company was founded in 1923 as “The Special Yarns Company,” and had been part of the new niche industry of synthetic fabrics and textiles. This was a whole generation of products that were chemically manufactured, some from organic products, like rayon (the company become Atlantic Rayon Corporation), and others from purely chemical processes. A British chemist, Sir Joseph Wilson Swan, is credited with the initial invention of rayon in the 1880s. The fiber was made from cellulose, chiefly wood, but other vegetable fibers as well. But it was a French chemist, Hilaire Berniaud, comte de Chardonnet, who brought the textile into production as a substitute for silk.[2] When I look now at the word “Textron” on the fifty year old box in which the manuscript still lives, I am aware of how the synthetic quality of the term seems to permeate my own writing of the time. As if, in some way, the paradigm of such spinning out of a base substance into a new slippery shimmering form were symptomatic of the time in which these industrial processes had permeated all aspects of contemporary life. The very word, “synthetic,” had an allure to it, emphasizing the transformative power of applied imagination. Was I manufacturing language along the same lines?

The events reported in Oh Oh are completely banal, just the stuff of a very young person trying to find their way socially and professionally. But it is the language that is so at once compelling and disturbing in its complexity and insularity.

The 1970s, duller than the 60s, was already a let-down, with the economic downturn following the end of the Viet Nam War and the Watergate conspiracy eroding faith in government, if any remained after the assassinations, riots, and upheavals of the decade before. And yet, in the 70s one felt part of a modern era, world where computers and robots were increasingly present, where concepts of natural language, in the work of Noam Chomsky among others, were being rethought from the perspective of structuralism and formal systems. Polyester was a thematic strain running through the culture in the form of burnt-orange suits, fake hair pieces, and snappy accessories.

Is there, in the mash-up technique of the style of Oh Oh something that is at once aligned with these artificial process-driven approaches and also at odds with its mechanistic certainties? As if taking up the implicit challenge and opportunity presented in Chomsky’s demonstration that the rules of syntax could produce sentences with nonsensical semantics. His 1957 example (from his book Semantic Structures) became famous: “Colorless green ideas sleep furiously.” Ideas of poetic language and artistic production were already being suffused with concepts of protocols and executable rules. Though I would not discover Chomsky until the 1980s, when I was in graduate school, hints of such formalism presented an the opportunity that poetics might embrace.[3] A few years later, as I encountered a community of writers whose training had included more intimate knowledge of Russian formalism, linguistics, and structuralist thought than mine, I would acquire a critical insight into my already developed practice. But in the early 1970s, my stylistic traits had developed intuitively, through an attachment to the comfort provided by the tensions between rhythmic patterns and dense associations across sound and sense.

Oh Oh is at once disturbingly alien and painfully familiar, like other style choices of the time, glimpsed in old Kodachrome slides and color snapshots that present an image of yourself you recognize, for sure, but with a certain twinge. I never thought of the encoded language as a gendered mode, though now I wonder. Later that year I wrote a parallel piece titled “Real Accounts” as an antidote to the linguistic ticks that had driven the composition of Oh Oh and other pieces at the time. I felt relief laying down the over-stylized conceits that seemed to cloak experience in code. In their place, I picked up other methods of transforming my identity with language.

PS Interested in seeing a bit more of the Oh Oh manuscript? Request it through comments on this Substack.

Water color mock-up for cover by the author, 1974.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Textron#Jacobsen

[2] https://www.britannica.com/technology/rayon-textile-fibre

[3] David Policar, “Colorless Green Ideas Sleep Furiously,” https://www.mit.edu/people/dpolicar/writing/proseDP/text/colorlessIdeas.html

Thanks!

Johanna, Thank you for sharing "Oh,Oh"! I would love to see more of the book. You know I always show my book history classes your "Testament Of Women". In a way a reprise of "Oh, Oh!" after decades of this wonderful and wearying life... J