My Little Lamb

Plastic lamb, gouache and watercolor, by JD

Molded in soulless, pale, green plastic, this little lamb has almost no significance to me. A curious thought that something years in my possession has almost no associations, calls forth no memories or poignant recollections. Weirdly, a single sentence I once wrote about the tiny thing lingers, also unmoored from any timeline: “Little lambs with very large heads have entered the sacred precincts.” If I could recover the circumstances, have any image of what “precincts” these were—a desk or some table where other objects formed a small community, would some more profound insights unravel? Would the presence of a keyring, small ceramic bowl, odd wooden toy cast off from an earlier moment trigger associations that would make the little lamb into something other than a dull and somewhat misshapen item? Would I see the pattern of those days, my life in snapshot, and read some emotional archaeology through its arrangement?

Things stay with us, often without our volition, as if they had sunk into a space-time curvature of orbital inertia. No real attachment is involved, just a steady state in which there is insufficient energy for the object to reach launch velocity and detach. Had I fulfilled my father’s dreams for me, I would have been an astronomer or cosmologist, calculating the possibilities of other lifeforms and exploring dimensions beyond our own. That didn’t happen, and I think the point at which this unfortunate lamb entered my life was when that window of possibility had already closed. I was set on the path to intellectual and pursuits driven by individual rather than collective vision. Or so I thought, not understanding the ways that consensus worked just as uniformly in art as in science, perhaps even more so.

I think this lamb might have been present the summer I got to know one of my former teachers from school, a printmaker turned painter in the era in which “the least thing that mattered” was the holy grail of visual art. What mark, color, tone, value might register just at the threshold of perception, tilt the viewer into awareness by being almost barely hardly present? He was spending the summer producing deep neutral backgrounds made by putting earth toned pigments into the gesso that made his expertly crafted canvases taut. The lines he painted by hand had the discipline of ruled edges and somewhere in the crimson-cadmium blend they created a spark of light against the somber ground.

This was all very sophisticated, and to my mind, a bit repressed, though I would soon follow my own explorations into an organic minimalist aesthetic that led me to an understanding of stochastic processes and non-linear events. These became the basis of work that has continued into the present. Another story. But even in my early twenties, I found the concept of the least thing seductive, as if it might fine tune one’s sensibilities to that edge where the definition of art/non-art could be detected. These threshold spaces have a profound allure, like the line between inorganic and organic compounds, or primordial soup and the emergence of living organisms. After crossing those lines, everything else is merely elaboration, but the distinction was where the edge of excitement lay.

The Bay Area art world where I encountered that teacher had a distinctive character in the early 1970s, having been the site of some exquisite photo-realist art by Robert Bechtle and Mary Snowden, some Pop Art spin-offs, such as the luscious canvases and painterly surfaces of Wayne Thiebaud and the witty narratives of William Wiley, and some significant conceptual work using language and photography.[1] That was the crucible within which we were formed, at CCAC, the California College of Arts and Crafts, where the generational spread of the faculty ensured some continuity of the rigor of the Bauhaus and older academic practices alongside newly current performance, post-studio, and media genres.

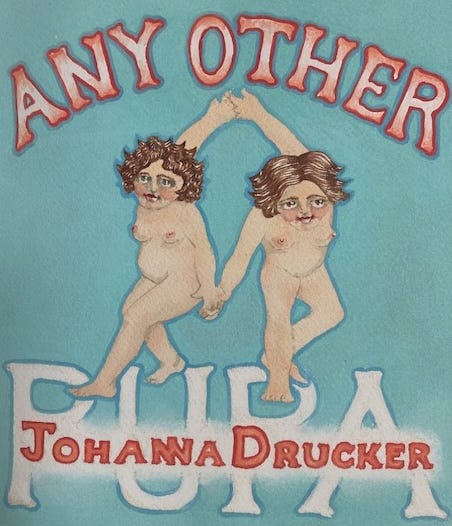

Any Other, title image, 1973, watercolor and chalk, JD

That was the same summer as the Watergate hearings, and I listened for hours to the radio broadcasts while working at my desk on drawings for a slide show of a piece titled, Any Other, that was a coded account of my high school romance. Typical of my writing in those days, it was densely figured prose, highly rhythmic, nearly incomprehensible. The text began: “Any one would have done, but it was this one, with her chunk ass wagging, made the Other feel secure.” The images were made in chalk pastel as a storyboard to chart the narrative of the two girls involved in elaborate games of role-playing and infatuation across gender and genre lines. In that phase, I had no community to offer reflection on my work, and wrote from a place of deep interiority. Steeped in French Symbolism, work by Arthur Rimbaud, Charles Baudelaire, and J.K. Huysmans, I felt alienated from most of “the moderns” with their spare economy of language. My engagement with the writings of Colette, Djuna Barnes, and even the still-lingering influence of the Brontës distanced me from my art school peers for whom Richard Brautigan and Gary Snyder were inspirations. I disdained the popular in favor of the esoteric strains of literary invention, even then.

By circulating a copy of my first book, Dark, The Bat-Elf Banquets the Pupae (1972), I had come into contact with a handful of poets in the orbit of Phillip Lamantia, the boy wonder who had been taken up by the Surrealists, including none other than André Breton himself, and been anointed at a young age for his gifts and his beauty. Now a senior figure, though actually just middle-aged, he had met with me and had a conversation about my work, his, and the traditions of dream and the unconscious. But I had no alignment with that movement beyond the acquaintance an art school seminar had provided. Surrealism as such seemed passé, antiquated, part of another era, quasi-baroque.

Interestingly, in my final year at CCAC, 1972, a group of graduate students intent on offering a view of a counter-traditions in the face of modernist orthodoxy, abstraction, and the avant-garde, had done a lecture on the Pre-Raphaelites. This was in the period when figuration was highly suspect and the mythological and narrative elements of that British group were as far from intellectual credibility as any visual art of any culture or period. The idea of taking that insular movement as inspiration in an era of psychedelics and rock music seemed far-fetched. And yet, the impact of that lecture was non-trivial, since it demonstrated the value of aesthetic self-definition and resistance to pressures of conformity.

And the lamb? There must have been more than one, for the word is plural in the description of the arrival of the animals. No doubt the “sacred precincts” were a workspace, and they appeared among pencils and boxes of colored chalks, invading as if to cause interference through their wayward wanderings. But while pens migrated and papers shifted without eliciting commentary, the arrival of the lamb seemed symbolic. Even for someone raised outside of Xtian faith, it is a potent image and this hard plastic animal suggests a vulnerable innocence liable to betrayal. Its companions, standing or walking, are long gone.

Still, the persistence of insignificant objects has its own force, as if to remind me/us of the power of inconsequential actions and things to have influence. No affect, no charge, no secrets attach to this and yet it is still present, its badly painted eye disproportionately large in the already bulbous head. Touching it, holding and painting its textured surface, I am connected to a long series of events that brought it forward with me to the present. A stack of unused post-its, a ballpoint pen inscribed with the name of a hotel in Sweden I stayed in ten years ago, a discarded boarding pass folded and used as scrap paper so that it has a bunch of references on it—significance and insignificance also hover on a dividing line. An object can leap from one category, changing status. The system of assessments and idiosyncratic metrics is constantly recalibrating meaning and value.

In spite of all this reflection, my little lamb, remains utterly without significance–but not without the power to signify. Curious contradiction.

[1] For a nice overview, see Constance Lewallen’s piece, https://brooklynrail.org/2017/11/editorsmessage/Bay-Watch-A-Snapshot-of-the-Visual-Arts-in-the-Bay-Area/