I was twelve the year I wrote The Letter. At ninety-six pages, the manuscript barely qualifies as a novel, but with unlimited adolescent humility, I put it squarely in that category. A dubious masterwork of derivative banality, focused on the unsuccessful love life of a hapless heroine, the project felt like a triumph simply by having been brought to completion. No one else among my schoolmates, bright, eager, and competitive though they were, had written a whole book. To consolidate my lead in the race to literary distinction among the eighth graders, I wrote a manuscript that year that was four times as long, in similar spiral notebooks, but this time with red covers. That epic, Roddy, was the story of three boys growing up in Liverpool competing for the hearts of various teen objects of desire. Well, it was 1964, after all when the Beatles’ “She Loves You” topped the charts.

As a child, I had had a quasi-magical relationship to writing. I carried a notebook and pen with me everywhere, convinced that at some–any–moment a spontaneous compositional flow was going to burst forth and I would simply channel text onto the page. Clearly I understood writing as a bodily emission I did not control. Since this never happened, I substituted steadiness of purpose and committed perseverance in my drive to fill the notebooks. Spontaneous channeling played a part as did the hubristic urge to prove my literary prowess. I did no planning, created no schematic outlines, and, amazingly, made almost no corrections in these handwritten texts. The composition went forward line after line, in an unbroken continuum relating events in even-handed and completely unremarkable prose. Here, for instance, is a scene in which the narrator has a change of heart towards another girl who has been assigned as a new roommate. The matter-of-fact tone is typical:

“That night I woke to the sound of sobbing. I looked over at Heather’s bed and I could see the covers move as her slight body shook with the sobs that rose and choked her. Suddenly, I didn’t mind her any more. All I could do was feel sorry for her.” (p.29)

From an early age and without a shade of doubt, I had always thought of myself as a writer. When I was about ten, I spent Sunday afternoons squatting on the living room rug, writing on school notebook paper, composing dialogue for a play. My mother, literary in her inclinations, informed me that the story was not the thing, it was the language that made a work important. She cited Shakespeare as inspiration and impossible benchmark, and that was enough to escalate my ambitions. While not exactly scoffing at my aspirations, she tempered my energies with checks that included criticism of my hubris and encouragement of a sobering modesty. Neither worked to quell my enthusiasm for the task of writing any more than they kept me from attempting the design of a perpetual motion machine one night before dinner. A marble in a curved cardboard rim, put into swinging motion, must, in my childish view, return to the same height from which it fell with each movement. Friction, my mother commented from the kitchen without pausing the dinner preparations, will slow its path. What a thing to say to a child. I saw immediately it was true, but grasped the deeper message. Hidden variables lurked in the realities of life.

Among my circle of friends there were other aspiring writers, all eagerly scribbling verses and short tales in a rush of hormone-driven outbursts. But no one wrote an entire book. Given its brevity, The Letter is more novella than epic, but the arc of narrative, character development, dramatic action and believable dialogue are fully present. The end pages of the notebook, after story ends, are filled with little jottings. I noted the times and titles of pop songs heard on the radio at night. I kept a draft of a poem meant to introduce the next book I had in mind to write. And there were a handful of other insignificant “notes to self” on various topics of passing interest.

The story in The Letter is written by and about a girl born to a wealthy family. She self-identifies as homely which is why she is sent off to boarding school–leaving her parents to revel in the company of her beautiful younger sister. At school she finds her first real “friend” who predictably dies. The friend is quickly replaced by another, the weeping roommate described above. At first the relationship is difficult, but it soon develops into an extended connection and the narrator is taken up by her new friend’s family when her own parents die. The influence of Louisa May Alcott and the Brontës is vividly apparent in the scenes and plot twists. The Scottish moors and pale young heroines who waste away as the central figure becomes an orphan are recognizable leitmotifs of romantic fiction aimed at female readers.

As per its title, The Letter is written as an epistolary communication. The narrator, Tabatha, is writing to “John,” who has asked to hear her life story. She begins by explaining she will do this so he can understand what she “is about to do now.” Following the account of early years, she provides details on her current situation—a hopeless love for the brother of her cousin, the same Heather character whose family has taken her in. This fellow, Peter, has talked caringly with her, befriended her, and captured her affections while appearing to be about to become engaged to her rival, Lizabeth. While his intentions are not clear, even through the narrator’s emotional fog we grasp Peter’s affection for our naturally virtuous heroine. In spite of her confusion, we sense that he intends to disengage from the mercenary Liz, who has no particularly affection for him and is only seeking a marriage of comfort and convenience, and to propose to Tabatha—whom he has already repeatedly “taken in his arms” and kissed. However, driven to desperation in her belief that “Peter” will never love her as she loves him, Tabatha determines to do herself in by throwing herself from the cliffs onto rocks on the shore below.

Death played a major role as a plot-structuring device in my tale. I felt no compunction about getting rid of siblings, parents, friends, best-friends, and others in order to power the narrative. The giant mechanism of story-telling seemed to be powered by energy rushing into the vacuum left by yet another untimely and oh-so-sad-but-inevitable demise. Messengers were always showing up in black clothes and speaking in somber terms, a sure sign another important member of the narrator’s social infrastructure had succumbed to the need to move the story along. My serial killings would have kept legions of tailors in business creating suitable mourning clothes.

When death did not suffice to engineer changed relationships among the characters, I resorted to the twin engines of jealousy and love. Jealously was licensed, sanctioned, and permitted because it was always generated by a bad woman, someone who was scheming in her own interests but without sincere emotion. Love, on the other hand, was an emotion never to be questioned, it came unbidden, was overwhelming, fated and fatal, and granted permission for absolutely any action because it was pure and potent. Love needed no justification or explanation. This was my cosmology and it governed the action of the novel. Love, jealousy, death—all had agency as natural social forces, directing the winds of change or spawning unexpected action. Desire for riches or fame, the tropes of lost heirs and mysterious strangers, played no role in the narrative. Mine was a stripped-down story-telling machine, distilled to basics: love and/or death. I had pretty much grasped the essentials.

As to the narrator, she lived in a world of teleological inevitability. From the very first page a sense of irrevocable fatality inheres in the tale. The narrative will end badly, it must, as the heroine is both in charge of her destiny—“what I am about to do”—and a victim of unkind fate–“I can never live without the one person I will ever love.”

I was twelve and not outside of the machinations of social life. Competition for affections of others ruled our schoolyard dramas. Trust was the lynchpin on which the story in The Letter turns. Whose word is to be counted as sincere, whose actions believed? Whom had I betrayed at the age of twelve? Whose affections had I played with and cast off? I’d had a series of boyfriends, flirted with girlfriends, seduced various young companions into chaste but still charged forms of intimacy. I was no stranger to manipulation or duplicity—or the thrill of conquest for its own sake. But I chose to narrate the book as a victim, a heroine sentencing herself to a tragic end in what she wrongly believed was a hopeless love. The character of “Peter” (or “John” to whom the letter was addressed) loved her, but as a clueless man, he was waiting for the right moment to make his feelings clear. In the final lines of the book, as she is poised on the edge of the cliff, he arrives and sees her “arms out pleadingly, tears falling freely now as she was knocked off balance by the wind.” And as she fell, the last sentences of the book state in that same matter-of-fact voice: “John ran to save her, but was too late. He was in time only to see her dashed to bits on the rocks below.” And in case the finality of that direct statement was insufficiently clear to my readers, I followed with “THE END” in good strong childish majuscules. No reprieve, no second chances. No mercy. Compassionate child.

Perhaps most surprising, the spiral-bound notebook is still in my possession. The confidence it embodies speaks across nearly six decades. The handwriting with its school-room loops and forward slant contains occasional curled swashes. These initial letters at the start of sentences are testimony to the concentration and absorption writing offered. The elaborate flourishes in the first stroke of a capital “W” or “Y’ have an obsessive intricacy identified with “girl writing” at the time–and the absolute pleasure of putting pen and pencil to paper.

But I was already on to other projects–the four volume Roddy manuscript followed this first exercise. But the real advance was that I had, through hard-fought struggle and much babysitting money, acquired a typewriter. This meant I had become a “real” writer. No more frippery or decorative lettering. Perhaps more important, I had begun writing extensively about my same-sex adolescent love affair and the difficulties and pleasures it was causing. Those texts, too, have lain unread for more than fifty years, articulate witnesses to the role of writing as a means of insight and self-reflection. More to come.

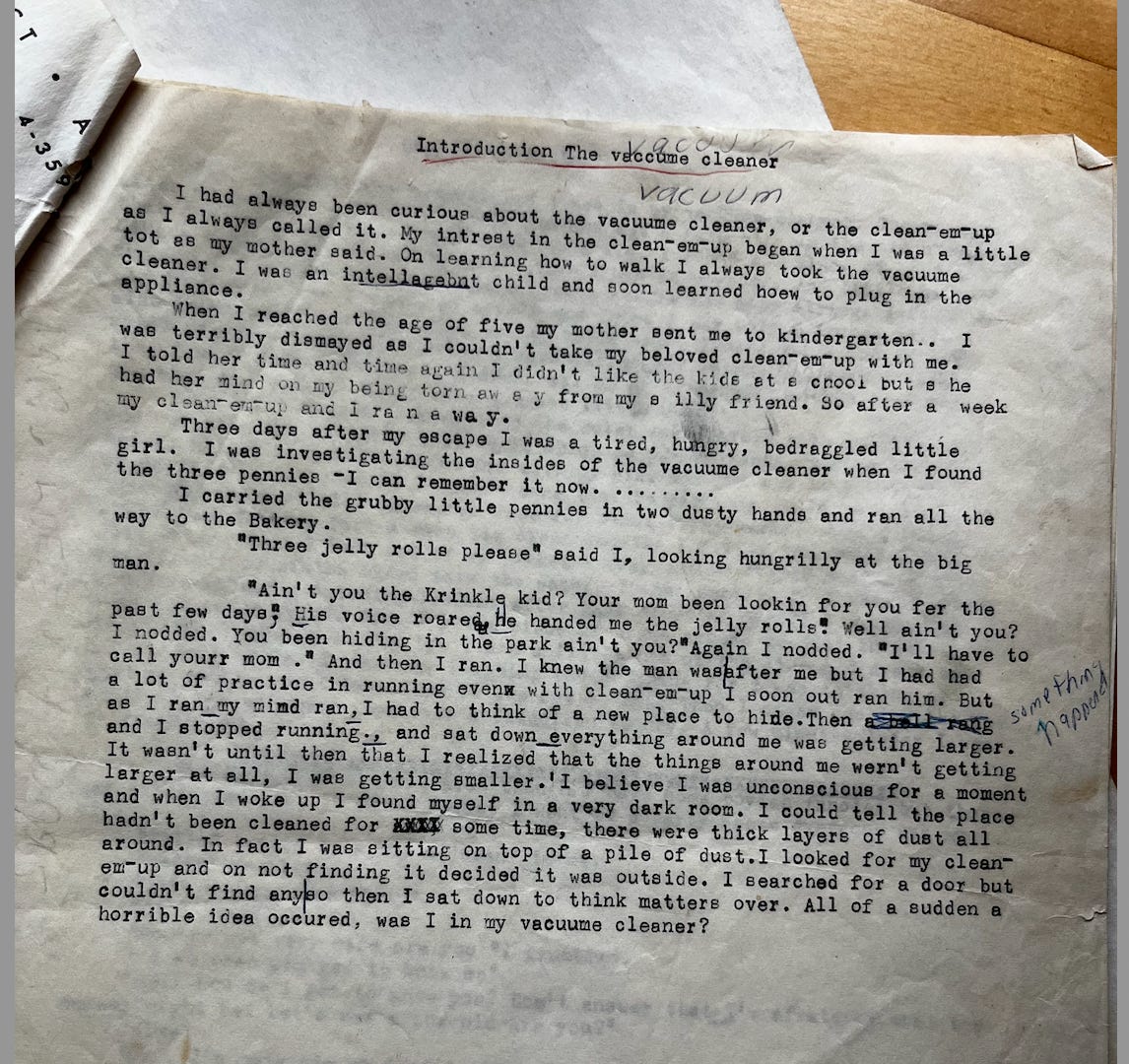

ADDENDUM: This posting provoked a response of a one of those childhood competitors who is still a close friend. Her email subject line said: “Ah hemm Girlfriend!” and text begins: “I beg to differ–you were not alone in your pursuits!” Her protest continues with details about her manuscript titled Tibbit: “undated but written when I was eight or nine or so, introduction and nine chapters, the last few of which were in longhand cursive. Don’t know what happened to the typewriter. The story of the adventures in independence of a little girl who ran away from mean kindergarten friends with her beloved vacuum cleaner and had mysteriously shrunk to an even tinier size to live her life inside the vacuum cleaner. Tibbit befriended a tiny boy, Merlin, murdered by an alley cat and a mouse named Isabelle.” By her own confession, the work took its inspiration from Mary Norton’s The Borrowers, and though it was not a sustained work at the same scale as The Letter, (ahem), it was surely and absolutely brought to completion. What other unread treasures lurk in our drawers and closets that might appear in this siren call across the decades? Thanks, Stephanie, for the note and for letting me share these images.

Thank you for this addendum and for the reminders of our childhood pursuits and ambitions. Back then, you set an unreachable mark for me to aspire to, and still do to this day, my dear old friend!