Marie Cosindas (1923-2017), Color Photographs

Bel Ami, 709 N. Hill Street, #103 and #105, Los Angeles, CA

Marie Cosindas (1923-2017), Color Photographs

Bel Ami, 709 N. Hill Street, #103 and #105

The painterly quality of Marie Cosindas’ color photographs is immediately striking. Though just seven of her images are on display at Bel Ami Gallery in Los Angeles’s Chinatown district, they make an eloquent argument for the virtues of a small exhibit—especially given the degree to which their intensity rewards in-person viewing. The original Polaroids were taken in the mid-1960s when Polaroid Land Cameras were enjoying an initial wave of popular success. The images on display are dye-transfer prints made in the 1980s using another color-rich photographic technique. Cosindas was already known for her extensive experience with color photography—sufficiently accomplished that she had attracted recognition from John Szarkowski, curator at the NY MoMA.

Polaroid. The very name has a nostalgic aura. In 1962 Cosindas had been recommended to inventor Edwin Land by her mentor Ansel Adams as one of a dozen photographers picked to test the new medium. This was just a few years before two commercial models, Colorpack (launched in 1963) and the Swinger targeting younger consumers (in 1965), were readily available on the market. The genius of his invention was that Land had combined the camera and the darkroom into a single device capable of producing a full-color image within minutes of the film’s exposure. This was nothing short of miraculous and the idea of instant-developing film found a receptive consumer audience. But Cosindas understood the visual potential of the sumptuous tones in the film, not just the satisfaction of an immediate image.

Marie Cosindas, untitled, 1966 Courtesy of Bel Ami gallery.

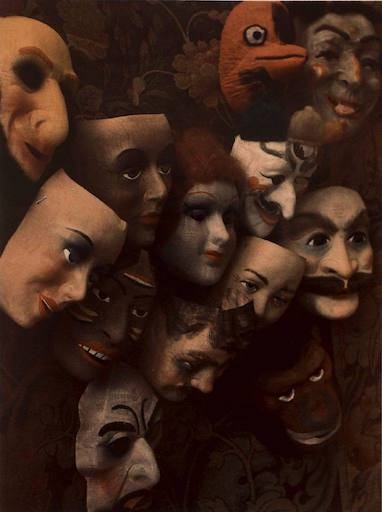

Like so many visual technologies, Polaroid has a specific aesthetic to it. The deep tones and a shiny surface create jewel-like images. Without any hint of preciousness, Cosindas made excellent use of these qualities, and the results were so painterly that she gave up her original impulse to make canvases based on the photographs and took these as a primary medium. Each of the images in the exhibit has a distinct intensity to it. A photograph of masks pulls their material papier-mâché thickness and hand-painted details right to the surface. The result is a thick almost-impasto palette of color. These qualities are emphasized by the decision to crop the crowded arrangement of objects in close-up on the eye holes and noses, lips and cheeks, and other features of their artificial physiognomies. The sense of the absolute thing-ness, the quiddity of the masks, is echoed in the saturated quality of the photo. Comparing the dye-transfer image on display with a printed reproduction of her photographs shows only a slight shift of brightness between the original and the print.

Marie Cosindas, untitled, 1966 Courtesy of Bel Ami gallery.

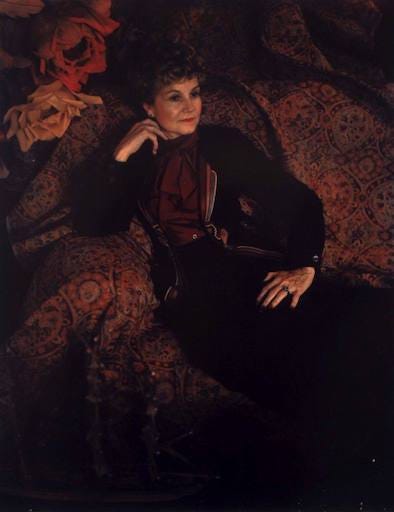

Among the seven pictures are two photos of unidentified, very elegant, women. In each the attention to materials—the silk dress and pattern, the deep color of a sofa, the thick stuff of two giant paper flowers with their outsized petals draped behind shoulders—almost dissociates the fabrics and textures from their role as dress and decoration. Almost, but not entirely–though lusciously presented, these colors and textures are not abstractions. The portraits are so meticulously observed that they are records of the time and place of fashion—what was being produced when and with what kinds of threads and textiles. As it happens, Cosindas formally studied fashion design in Boston as well as taking painting courses at the Museum School. But her attention to fashion in her photographs reads more like cultural studies than modern design practice. The postures these women strike and the accessories they wear are so of their moment that they serve as incisive time capsules from 1966, the year of their original production. They let us see into a fully replete world, now vanished.

Marie Cosindas, untitled, 1966 Courtesy of Bel Ami gallery.

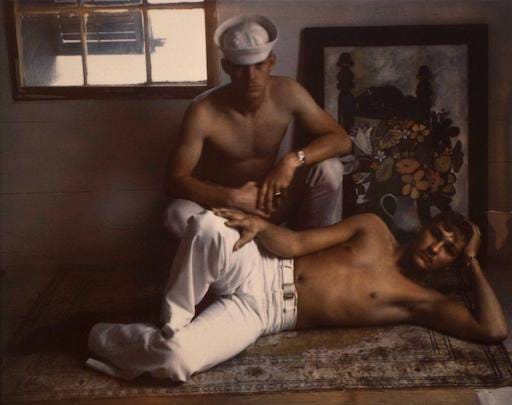

But the images are also full of literary and art historical references. An image of two sailors in Key West, both stripped to the waist above their spotless white trousers, shows them posed with a painting in the background depicting an abundant floral arrangement. This suggests an immediate association with Jean Genet’s Our Lady of the Flowers (1943) and its gay sub-culture connections. The photo also invokes the work of Paul Cadmus, the American artist who painted “sailors” and “floozies” in the 1930s with frequent homoerotic overtones. In another image, two male body builders are as sculpted in their physical form as their gelled hair and satin shorts, and again the rendering calls unflinching attention to the material qualities of their appearance. The suggestion of eroticism is more subtle in this image, if present at all. The obvious pursuit of an ideal of masculine strength and physical beauty predominates. These figures seem driven by aesthetic idealism rather than sexual gratification.

One image, Paula naked, shows a pre-pubescent girl posed with one leg raised and bent at the knee shielding her genitals from view. The image is disturbing for what feels, now, like exploitation of a minor, and must, even then have had some shock effect. Fifty years ago, the figurative painter Balthus created deliberately erotic and provocative images of naked girls that were accepted without any critical unease. Cosindas’ image might be a quotation of the posture represented in his Thérèse dreaming (1938) or Girl and Cat (1937), but Balthus so often posed his figures this way that Cosindas must have known the reference. In fact, one of the persistent features of her photographs is this self-conscious citation of other images and tropes. Though not on display, the still life Polaroids and many of her other portraits show the influence of Dutch masters and canonical artists, like Francisco Goya.

The final image on view is a still life with dolls, again loaded with an inventory of textiles and jewels, painted porcelain faces and wigs, the many details of manufacture and decoration that link these objects to their own moments of production. Once again the cropping is tight and pulls the details of made-ness in the depicted objects into a colorful dialogue with the Polaroid pigments. Cosindas is using the medium to maximum effect.

The name Polaroid derives from the polarization of light produced when it passes through a layer of crystals embedded in film. This was Land’s invention and the outcome of his studies physics and optics in the 1920s and 30s. Apparently, he passed through Harvard briefly without getting a degree and University after he moved to New York used to steal into the labs at Columbia so that he could tinker with equipment and chemistry. Mythic tales, but real, and his engagement with the electromagnetic waves that make up light was what led to the invention that embedded the processes for filtering red, green, and blue light in a single multi-layered package of film and paper activated upon exposure. Before that, color photography (which had existed for a century) involved darkroom skill beyond the average family photographer or affluent teenager on a date snapping away with a Swinger.

The cost of a roll of Polaroid film was considerable, but the instant gratification was worth it. Clicking the picture, pulling the thickly layered film and paper stack from a slot in the back of the camera, and then counting the requisite number of seconds added to magic. Instant color film was a radical innovation. The fact that the film did not have to go to a lab for processing also created a subculture for photography that might have been subject to censorship had it been viewed by technicians in the processing. Many tales were told of self-documented autoeroticism and other pornographic escapades.

Another pioneer in the Polaroid medium, Lucas Samaras, provides an interesting contrast. Samaras’ self-portraits from the 1960s are, like Cosindas images, took full advantage of the unique beauty of the technique. Samaras pushed Polaroid into surreal distortions and biomorphic fantasy by smearing and manipulating the medium. Cosindas, by contrast, worked in the long tradition of Western fine art, her gaze appropriating tropes of Renaissance and Baroque composition. Though both were Greek by birth and family, Cosindas was a decade older and brought her study of fashion and art history to her work. Perhaps her mentor Ansel Adams and his classical sense of composition had an influence on her work, as well as the other photographers within the Heliotrope group she helped co-found around 1962. These included, for instance, Paul Caponigro who explicitly stated that the chemistry of photography was part of the vocabulary with which he worked—emulsions, fixers, the salts and so on.

Tom Wolfe, the stylish celebrity journalist wrote the essay for the monograph Marie Cosindas, Color Photographs (New York Graphic Society, 1978). A copy of this publication was on display in the gallery, a welcome addition for its historical as well as critical value, not to mention its wit and style. Wolfe is featured in one of the series in its pages appropriately titled “The Dandies.” Other famous, and some now less known, figures are also featured in the portraits, such as author Truman Capote, Paul Newman, Robert Redford, and Faye Dunaway. Some were clearly then-recognizable celebrities. Artist Richard Merkin’s face was part of the collage on the cover of the Beatles’ Sargent Pepper album during the mid-1960s when he was moving in the same circles as David Hockney, R.B. Kitaj and other figures associated with trendy Pop culture. But turning a page to reveal a portrait of Ezra Pound (looking like he is being played by Willem Dafoe) produced a shock moment. The intimacy and objectivity of the portrait brought the complex poet almost too close.

Cosindas moved in many fascinating intellectual and artistic circles. Her work was shown extensively, she had a solo show at MoMA in 1966, just about the time of the photographs in the Bel Ami exhibit. She made various technical interventions as she experimented with the Polaroid process—taping gels on her lenses or manipulating the temperature in the room to alter the rate of development in the chemicals. Though she was not, and is not, entirely forgotten, she was a pioneer in 20th-century color photography whose work still pushes the limits of the medium to exceptional degrees of saturation in which subject and treatment entwine. That she was one of few women to rise to prominence in those professional realms is evidence of both her talents and the determined persistence noted by those who knew her.

Polaroid formats were small—a little less than 3” x 4” with 4” x 4” maximum image size. Sheet film for larger Polaroid cameras appeared in the mid-1970s. The prints on display at Bel Ami are about twice the dimensions of the originals. Given their depth of detail, it is hard to imagine peering at smaller versions as these are so completely absorbing.

Precisely how the dye transfer production of these prints is related to the originals is unclear, but it was used in Technicolor film production as well as for continuous tone photography. Unlike pigments, which remain separate from their medium, dyes dissolve and saturate their substrate. In other words, dyes soak into the paper and become one with its fibers to produce a deeper and more visually absorptive effect than pigments. But where dye transfer relies on cyan, magenta, and yellow as its basic components, the Polaroid process was constructed on principles of optics that emphasized the polarization of light through green, blue, and red filters. No information on the technical details of the remediation from original to print was provided in the exhibit, but the images compare favorably with the reproductions in the Wolfe publication. This small group of Cosindas’ works shows dramatically how much an artist’s thought process can be stimulated by their engagement with the technological potential of a medium. An absorbing set of gems, well worth a visit.

Bel Ami has two spaces in its gallery. The second space is currently occupied by the work of Agnes Scherer, the outcome of a project-based residency for the German artist during a stay in Los Angeles. Cut out elements, figures, frames, and iconographic references to emblematic prints from Renaissance studies of antique objects all appear in the works, which are mainly colored pencil and graphite. A large kite form made of paper with similar iconography occupies one room, its solid form in curious tension with the appearance of lightness in the sun-suffused space. Vivid felt marker drawings enhance the presence of the drawings giving the the semi-translucent object a robust energy. One virtue of the Scherer exhibit is its demonstration of the ways projects afford an opportunity for experiment, letting an artist explore a process outside their usual practice. This space of exploration is an essential aspect of artistic practice and not always appreciated in an era where an artist’s recognizable brand has to define their commercial identity for a market. These works had an inventive lightness to their collaged, layered approach. They show ideas and concepts, rather than finished products, giving a glimpse of the working thought process of the artist.

The exhibits are on view through November 18, 2023.

*N.B. The photographs are on consignment from Bruce Silverstein Gallery in New York. Series titles, as well as those of the photographs, appear in a checklist of the MoMA exhibition and the 1973 publication on display in the gallery, but not all individuals are identified.