Gabriel Pomerand, Saint Ghetto of the Loans

(World Poetry Books, 2023). Translated by Michael Kasper and Bhamati Viswanathan

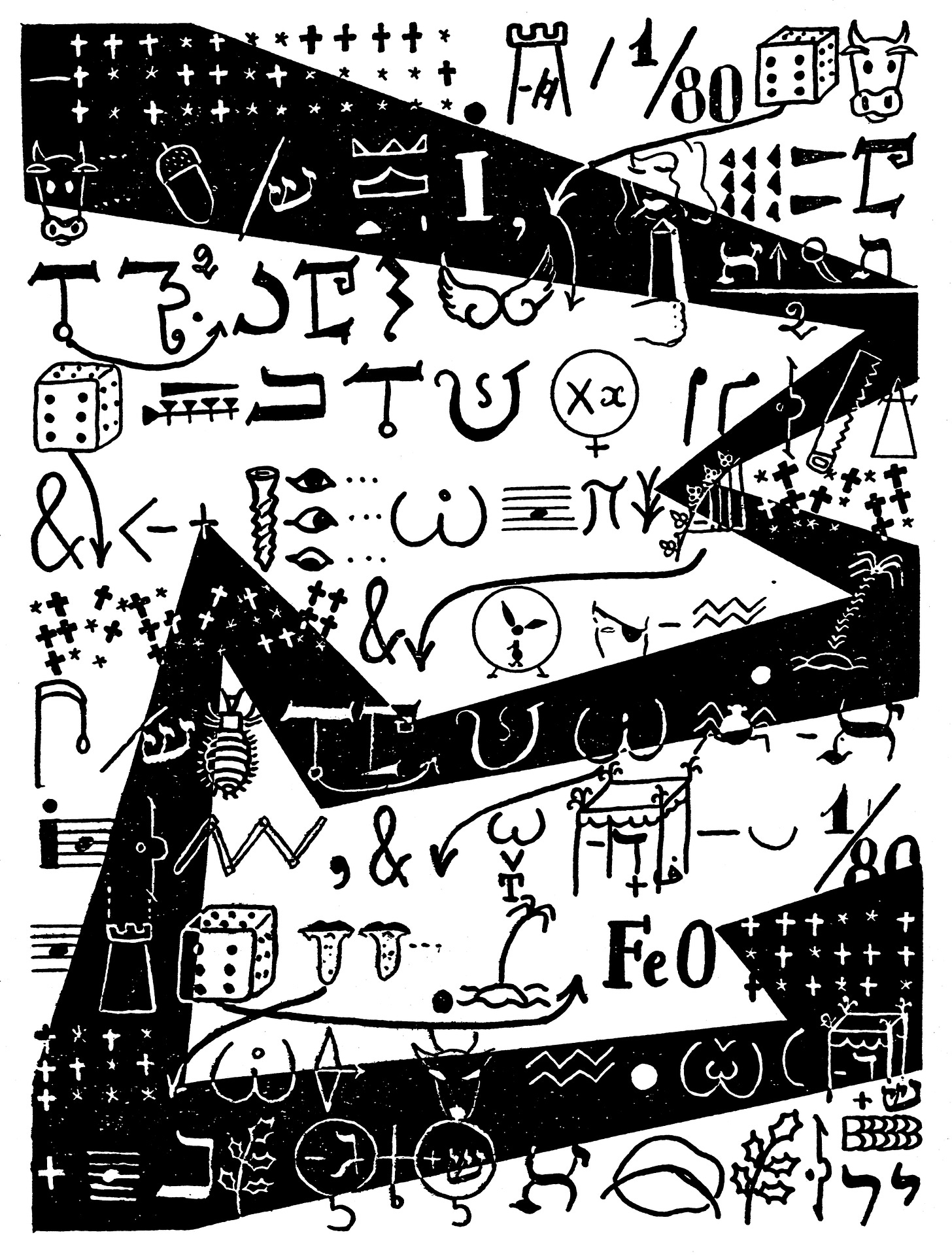

Cover of Saint Ghetto des Prêts, original edition.

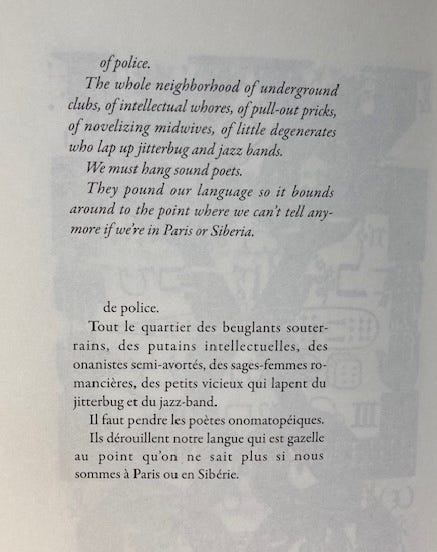

Gabriel Pomerand’s 1950 publication, Saint Ghetto des Prêts, just issued by World Poetry Books in a new edition as Saint Ghetto of the Loans, is one of the most systematic and sustained “metagraphic” works of the 20th century avant-garde.[1] The original book consisted of a series of poems set next to the author’s graphic “translations” in visual signs and glyphs. Baffling at first sight, the graphics literally present the poems in puns and rebus-like sound-image connections. The easiest way to this relation is to read the French verses out loud, tracking the parallel structures of sound and graphic device.[2] The visual renderings call attention to the poems as writing whose code—letters—is usually ignored. Here the letters are reinvented, mostly augmented or replaced with visual signs meant to be pronounced. The Lettrists saw themselves as researchers into the study of signs, and Pomerand’s book was the outcome of an extensive effort at compiling a rich graphic inventory.

The poems in Saint Ghetto present a portrait of the quarter, Saint Germain des Prés, which in the post-War period in which Pomerand was writing, was the site of a rich literary scene. Jean-Paul Sartre, Boris Vian, Jean Cocteau and Isidore Isou, among others, flicker through these pages, each coming in for sometimes scathing or irreverent depiction in Pomerand’s text. This is a world of prostitutes, drugs, sex, exploitation and opportunism, not a romantic literary feast. Strains of the Comte de Lautréamont’s Chants de Maldoror, Charles Baudelaire’s themes of spleen and ideal, and François Villon’s criminal behaviors, weave through Pomerand’s updated and unexpurgated slang-ridden poetics. He uses the vocabulary of bodily functions, references to the under-belly of urban life, and dark domains of the psyche. These are not polite works, far from it, and they are redolent with paranoia, suggestions of the criminal life, a slightly sordid Bohemianism and other unsavory themes.

The graphics are what make this such a remarkable work (rather than the texts, which are perhaps a bit slight). As translator/scholar Michael Kasper makes clear in his useful, succinct, afterword, Pomerand’s graphics have a systematic structure. In the first page layouts they are quite linear, making use of that vast inventory culled from many sources—magical, alchemical, kabbalistic, and popular forms of sign language, information graphics, cartoons, and every other imaginable source. Hebrew letters and references to Pomerand’s Jewish identity are visibly present. Kasper points out that the first pages of graphic renderings even preserve the poems’ punctuation to help the reader correlate the verbal text with the visual sentence by sentence. As the work progresses, the graphics become more animated and large patterns or figures break through the linear organization in dramatic gestures that structure the pages in bold black and white designs. But the graphic-phonic translation is sustained throughout. The graphics are literally translations of the texts.

Metagraphic and accompanying poem text. By permission, World Poetry Books.

“Metagraphy” was the term Pomerand adopted for this practice, used to “model the figurative essence of creation.” Pomerand, who acknowledged his debt to the ideas of the founding figure of Lettrism, Isidore Isou, says he was determined “to replace a debased, dried up symbolism—that of words—with a new symbolism, torn from the flesh of acquired ideas.” The work was radically inventive, deliberately aimed at producing a new graphical-poetics as a critique of what he saw as the exhausted condition of modern verse. Hubris and ambition were never in short supply among the Lettrists. They strove for nothing short of a completely new foundation for poetry that claimed to eliminate semantics through the use of symbols and compositions produced at the level of the letter. This poses a challenge for reading, even with a knowledge of French, since the meanings of the graphic signs are not always obvious.

This book, originally issued in a somewhat larger format and including a “special” print run of 40 copies on fine paper, is a singular accomplishment. Though the prolific outpouring of Lettrist works included some other examples of sustained graphic notation—Isou’s Journal of the Gods and Maurice Lemaître’s Canailles (Scoundrels), also both published in 1950—much of the visual work of the group was done in paintings, in film, or other graphics. The sustained systematicity of Pomerand’s metagraphic translation is remarkable. Having the work available again provides an opportunity to revisit its idiosyncratic attributes and graphic imagination. As the book’s blurbs and other commentaries make clear, I am not the only person to accord Saint Ghetto cult status as a lost and unique literary work.

Kasper and Viswanathan’s English translations are crisp and sharp in tone, their economy underscoring the acerbic feel of the poems. In Kasper’s notes he points out that the correlation between text and graphics through puns and semantic rhymes cannot be preserved in English translation. A foot designating the French word “pas” for “step” or for the negative “not” in “ne pas” has no easy equivalent in English where the sound connection is lost. So be it. The three-part presentation of original text, graphics, and translation none-the-less provides a solid basis for reading/viewing and puzzling out the metagraphic work.

The Lettrist movement had a significant impact when it first appeared in Paris in the years immediately following World War II and through the 1950s. (One remarkable document is a 1955 filmed interview with Isou and Lemaître and Orson Welles!)[3] And yet, it is nearly forgotten today. Why? The answer is complicated and has in part to do with Lettrism’s having been eclipsed by the overwhelming profile of the Situationist International, an offshoot fostered by Guy Debord. But other aesthetic factors also play a role. The politics of literary and art history makes Lettrism an interesting phenomenon. The quirks and factors that determine which elements, works, or individuals succeed in canonization and which fall away are not predictable. Lettrism blazed into being and claimed attention through aggressive public relations campaigns. But the works it produced are idiosyncratic, often obscure, sometimes offensive—deliberately so—and continue to baffle even astute readers of avant-garde and innovative literature.

Pomerand’s book provides a good example of the forms of bafflement Lettrist work produces. Along with Lemaître, Pomerand was part of the original group that formed around the Romanian emigré Isidore Isou (born Isidore Goldstein) its founder. The 20-year-old Isou arrived in Paris in 1945 with a pile of already written manuscripts and unlimited ambitions as well as a letter of introduction to the distinguished editor at Gallimard, Jean Paulhan, an established figure in French literature. The editor of the Nouvelle Revue Française, he had a track record as a prolific author and critic. Paulhan happened to be out of the office on the day that Isou arrived and supposedly Isou waited until he could meet Gaston Gallimard himself, bypassing Paulhan by pretending to be there to do an interview with the chef. Young, handsome, and tremendously charismatic, Isou was incredibly persuasive. He had no doubt about the significance of his own work–and he succeeded in convincing others.

In 1947 Gallimard published Isou’s Introduction à une Nouvelle Poésie et une Nouvelle Musique. Another work, titled The Making of a name and the Making of a Messiah, Isou’s memoire (also published in 1947), gives a sense of Isou’s self-perception. He believed all of literature to the point of his appearance had been a period awaiting his arrival—which was a moment of fundamental transformation. He really believed this. His literary prowess was matched in his mind (and behavior) by his sexual prowess—he claimed to have slept with hundreds of women. Isou, or the Mechanics of Women, his 1949 novel, was an obsessive erotic work focused on a 16-year-old young woman and resulted in a brief prison sentence. The sheer prolificness of his output in this period is staggering even if, as he claimed, the suitcase he carried on arrival to Paris was stuffed with manuscripts. By 1950, at the age of 25, he had published at least five highly provocative critical-theoretical works including Traité d'économie nucléaire: Le soulèvement de la jeunesse (Treatise of Nuclear Economics: Youth Uprising) (1949). This book, which emphasized the youth movement as a political force, anticipated the work of other political theorists and activists whose writings contributed to the events that led to the activities of 1968. “Life is the purpose of art,” one key Situationist poster read, and the graphics in the streets in 1968 were full of exhortations to revolution and resistance.

In addition to their literary and political texts, the Lettrists produced films and film theory, texts on music, material culture, novels, graphical works, and an endless number of attacks on prominent figures. They shouted interventions at public readings and lectures. They wrote letters protesting the history of Dada and Futurism, claiming these early 20th century artists had committed “plagiarism” in reverse—copying Lettrist ideas in the past without giving proper credit to the authors who appeared in the next generation. Their antics gained them notoriety within the Paris scene, but also within the international networks including CoBrA, Situationism, Fluxus, and other movements concerned with the power of art to produce political transformation.

But whatever its political aspirations, at its core, the Lettrist aesthetic was focused, as noted above, on the use of letters as signs in order to subvert conventions of meaning in language. Letters as signs were conceived as the basic components of poetry. By changing the very code of writing, Lettrism would tilt the history of literature from its amplic/expanding phase to its chiseling/condensing phase according to an overarching historical narrative. This atomization was taken to hyperbolic extremes by Isou as well as the first adherents to his platform of Lettrism—Lemaître and Pomerand. This intervention was meant to reinvent literature as letter-ature.

This brings us back to the challenges posed by Pomerand’s work—as well as that of other Lettrists. On the cover of Gabriel Pomerand’s book the handwritten title is followed by the additional word, “grimoire.” By invoking medieval magical and alchemical works, the word grimoire, positioned among the floating field of signs, signals to the reader that the book is a cryptic text that will need to be deciphered as well as read. Heads, letters, figures, crosses, a Jewish star, bits of numeric and other sign systems all swarm across the paper. Is this array of symbols meant to be read? Are they meaningful or just a mess of visual soup? For many readers, the combination of graphical elements in the poetic composition seems to cancel its identity as a text.

Technically, the cover would have been simple to produce even in 1950, when it first appeared, since it was created from two separate print runs of a single color each. The interior pages are line art in black and white, not requiring expensive half-tones or color separations. The book could have been printed inexpensively. The production quality of Lettrist publications tended to go down over time as they relied increasingly on copiers and duplicating techology Isou’s Nouvelle Poésie had appeared in the standard and readily identifiable format of the prestigious literary publisher, Gallimard. the year before. By its very look, Isou’s book presents itself as authoritative, a work whose value is assured by association with a tradition of serious literary publishing. By contrast, Pomerand’s work was a small press edition. Now, of course, a copy of the original sells for several thousand dollars, if you can find it.

Reception history of visual artifacts is often tied to their appearance of importance, their production values. In the 1990s, when Yale graduate students in Art History were introduced to Lettrist materials, they dismissed them out of hand in part because they had such poor production. How could anything made on a duplicator and stapled through the spine be important? But, like much of the work that came from activist communities—feminists, people of color—and from alternative literary publishers in the 1960s, the Lettrist work made use of available print technology that gave them some control over the production. Tracking the physical transformation of artists’ books, Fluxus publications, Concrete poetry, and Situationist works through the 1960s reveals an interesting history of rising and falling capitalization, marked in the quality of production. Some ephemeral seeming works get recuperated later—like the handmade pamphlets created by Russian Futurist book artists in the 1910s—and others get shunted aside. Steve Clay and Rodney Phillips’s A Secret Location on the Lower East Side: Adventures in Writing 1960-1980 (1998) is a useful study of mimeo and other accessible print technologies as an aspect of literary culture. Again, these relationships are significant not only for their impact on initial production, but on later critical reception. Every scrap of an envelope on which Emily Dickinson scribbled a verse gets examined for its material as well as textual features, and rightly so. Why not the cracking plastic covers of Lemaître’s Lettrist productions on standard office paper?

Lettrist projects, by the basic tenets of their practice, pose problems of legibility. Pomerand’s signs intentionally suggest alchemical formulae rather than written text. The lines are meant to be performative, to have the power of dynamic action with outcomes. Not coincidentally, Pomerand performed sound poetry in cafés. Language is neither passive nor descriptive, but instrumental and active as the signs add up, detract, perform their transformative effects. They do not represent or stand for meaning even if they translate into sound. They enact a form of signaling—like a rude hand gesture or a friendly wink. The complicated black and white drawings are the quintessence of Lettrism.

As noted above, Lettrism barely registers in current histories of art or literature of the post-War period in spite of its importance on the avant-garde in Europe in the 1950s. It was the crucible from which Situationism first formed through Debord’s connection to Isou and then his break to form the Lettrist International. The in-fighting and endless struggles for power and recognition were not pretty, and even with his closest companions, Isou quarreled constantly throughout his life. Isou’s megalomania did not sustain his career, or later reception, and to a great extent he lived in isolation after the first flush of fame. Pomerand committed suicide in 1972 in his mid-40s. Lemaître lived to an advanced age, bitter at the lack of recognition he felt he deserved. But what do these figures deserve? At the very least, their attempt at radical reinvention of literature at the level of sign is significant. On the one hand, it failed, literature continues to be produced as text. On the other, it was an intervention at the level of code, an important conceptual principle. As to the impact on politics–would Situationism have arisen without Lettrism? Was Isou the force that brought youth culture to the fore? Speculations at this scale seem pointless. Lettrism was more widespread than the handful of examples cited here would suggest, and the painters Roland Sabatier, Alain Satié, and Gil Wolman and others produced sustained bodies of work of significant interest for their dialogue with pop and media culture.

Ultimately, the point made by Pomerand’s book is that codes of writing are central to literary composition and reception. Few writers attend to the graphical foundations of their texts and in critical discussion, writing and the components of visual semantics are often overlooked, ignored, or denigrated. The fact that Lettrism has been given comparatively little critical and historical attention attests to this prejudice—as if these graphical texts were not poetry. But they are. And as Saint Ghetto demonstrates, they extend poetic practice by calling explicit attention to its instantiation in visual signs.

[1] This is a new, revised, edition of the Ugly Duckling Press version published in 2006. Michael Kasper provided information about the changes. The preface by Jacques Baratier was added. Baratier had made a film for which the text of Saint Ghetto was originally a voice-over. An additional bibliography and also contributions from a number of acknowledged experts tightened the translation.

[2] I cannot “read” the graphic signs as sounds, they are too ambiguous, but I can make sense of them when I pronounce the French text.

[3] Frédéric Aquaviva has produced substantial documentation and critical study. See: https://www.mauricelemaitre.org/what-is-lettrism/