Pristine as the year they were printed in 1974, these six publications from the editor Guy Schraenen seem to have arrived by time travel from half a century ago. Everything in their production is of that era. Their aesthetic properties have become more clear with time. They are each exemplary instantiations of a sophisticated European conceptual art sensibility of the 1970s. Two are larger format (approximately 10” x 13”), three are smaller octavo works, and one is a collection of artists’ postcards folded into a card stock cover. Each deserves at least a few points of individual attention.

Bernard Heidsieck, Foules (1974), open to show the portfolio structure and color of the papers.

Bernard Heidsieck’s Foules (Crowds) is printed on sheets of colored card stock with the quality of construction paper. The unbound folded pages are contained in a crisply scored dark grey cover that serves as a portfolio. The strong blue, green, orange tones of the sheets wash out the halftone photographs of groups of people altered by Heidsieck’s biomorphic balloon forms and handwriting. Like many conceptual works, the book documents a larger project, “100 Crowds of October 1970,” that were collages of images and automatic writing produced within the time constraint of the single month. The pressure of “extreme speed” was intended, as per the introductory notes, as a way of engaging with the crowd in order to disappear into it. The works were conceived “to not be read” and to serve a therapeutic function by the fact that the acceleration left no chance for revision. “The gamble,” he says, “succeeded.”

Five hundred copies of this portfolio book were printed, which says something about the scale of circulation. Original sales price for this object would have been modest, in part because one of the primary goals of these publications was to shift art away from the gallery and make it available in broader contexts. The presence of these objects in Los Angeles fifty years after their publication is a vivid demonstration of the ways books move in the world. It would be interesting to light up a map of where the rest of the numbers in the edition reside.

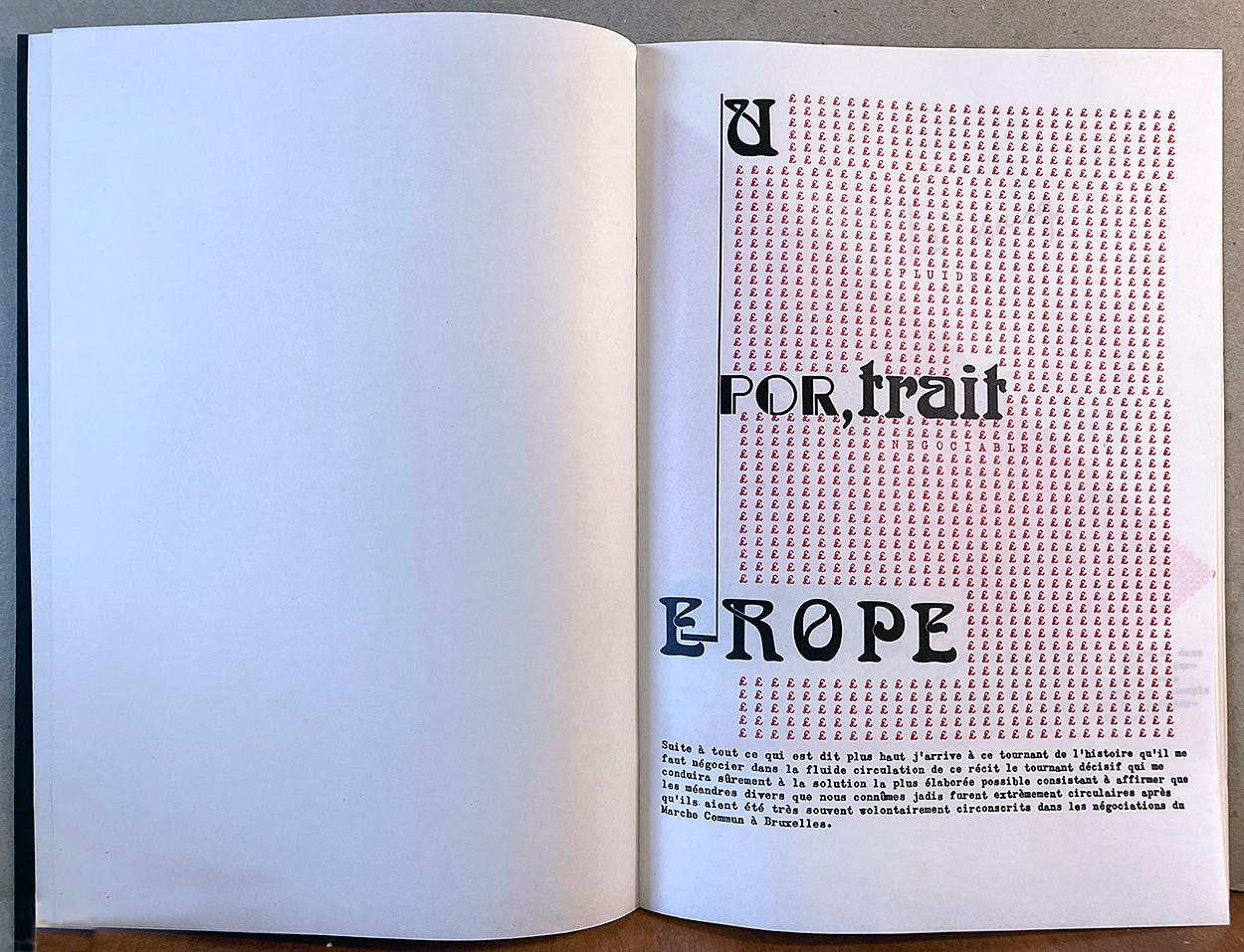

Henri Chopin, 29 Novembre 74, Portrait des 9 (1974), combining of typewriter and other lettering techniques.

The volume by Henri Chopin, 29 Novembre 74, Portrait des 9, with its stiff black cover and silky smooth pages printed on one side only, is sensually rich. The text is a diatribe against the TVA—Taxe sur la Valeur aAjoutée (Value Added Tax) applied to all goods and services in the European Union. (Though the European Communities had formed in about 1973, the official EU was only established twenty years later, but a version of VAT was imposed from about 1959-60.) On the title page, the “U” of Europe is lifted out of the word, and the syllables “por,” “trait” separated by a comma and space. This enigmatic treatment is set into a typewritten field of British pound signs and text about negotiations and circulation of value. The collapse of financial and aesthetic language into a single context forms the core of the text. Four more pages follow, each using the typewriter as a primary production instrument for the poems titled: “The fluid blood,” “Negotiation,” “Glory TVA,” and “ZERO” (this last set in a graphic resembling a cross). Untangling the text takes us back into historical references and perspectives difficult to understand without careful analysis, but the pages are still vividly beautiful. Again, five hundred copies were printed, of which twenty contained an original, non-editioned, work by Chopin.

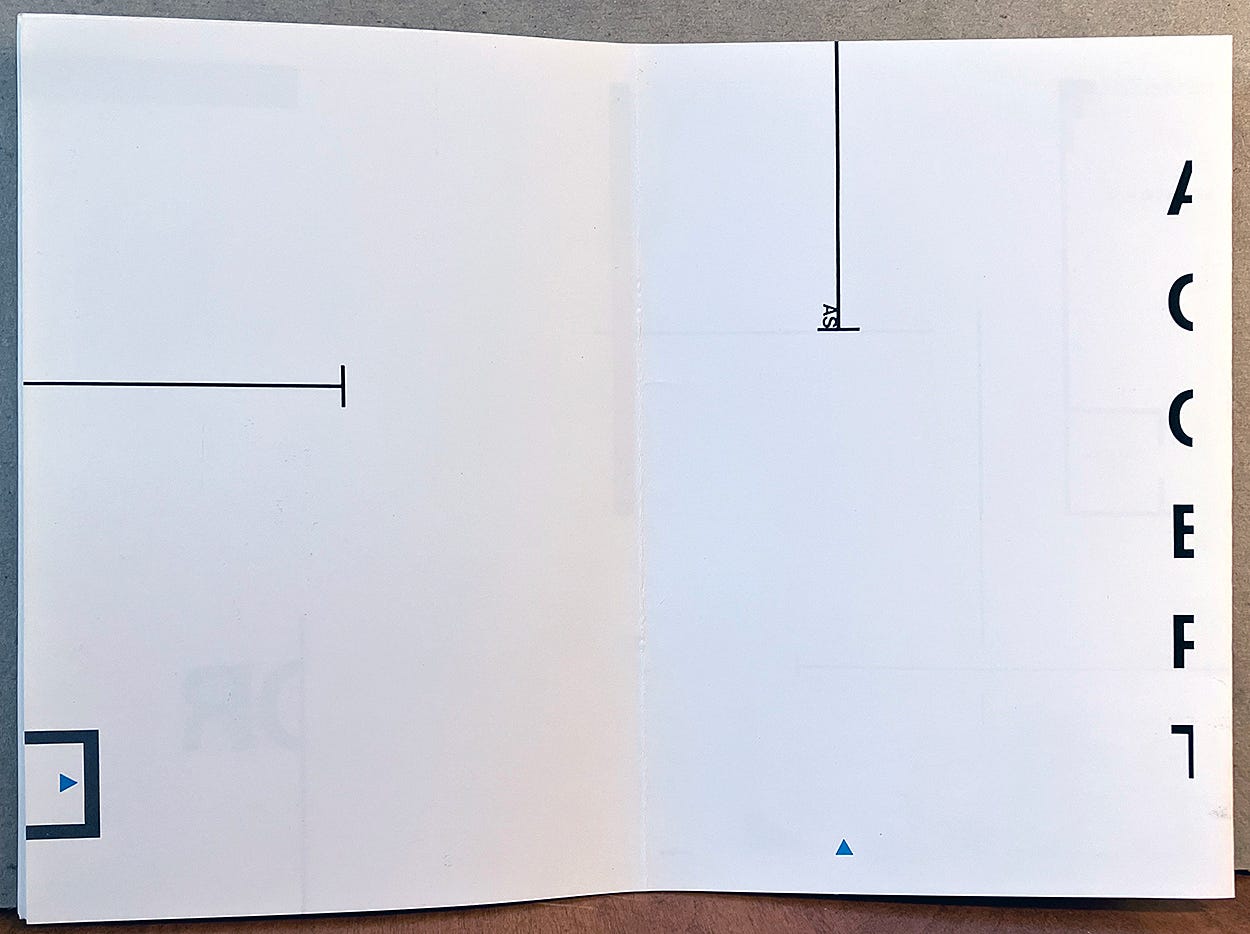

Of the three smaller books, one is an offset reproduction of more typewriter poems by Chopin, Mil 1000 mille dates, another is an ephemeral work by Bernard Villers, Geometrie Variable which consists of a half a dozen drawings in reference to the print of a ginko leaf, and then For Rent, a diagrammatic study of an apartment, rendered by Peter Downsbrough in a sequence that expands the architectural plan of the space into a dialogue with the spaces of the small pamphlet. These are clearly conceptual works, idea driven and spare, they require considerable viewer engagement to complete the experience they provoke. No lush editions here, no rich illustrations or compelling narratives, no poetic refrains or personal confessions. A few lines, a scattering of signs, minimal graphics and puzzling scraps of text are all that is offered. Paradoxically, in their minimalism, their stylistic features embody the recognizable branding of each artist.

Peter Downsborough, Rent (1974), takes features of an architectural plan and places them into a pamphlet.

The collection of postcards includes works by a regular list of exhibitors at Schraenen’s Galerie Kontact in Antwerp and each is a unique, if highly reductive, approach by the artists whose key aesthetic identity would have been identifiable within the context of the time. One shows an emptied silhouette of Notre Dame with a scattered crowd in front. Another is a typewriter poem stating “This is not a sculpture by a modern artist,” and then “it is only the nose of a modern artist,” thus clarifying the semantic value of the triangular form (referring the René Magritte’s famous “This is not a pipe” canvas). A third has a black triangle entering on every edge, a gesture that could be read as calling attention to the boundary of the card and its autonomy and connection to the surrounding context. And so on. Each has an idea and distinct execution to it, though many of the artists are now obscure. Each requires effort by the viewer to enter into the conceptual frame and complete the work by engaging the minimal cues.

The editor behind these editions, Guy Schraenen, was involved in a considerable range of curatorial, critical, and artistic activities. He first opened a gallery in 1965 in Antwerp that provided a venue for cutting-edge work as the trends in visual art shifted from post-War abstraction to the minimalist and conceptual work that appears in these publications. He had extensive networks throughout the European art world whose activities were no longer easily subsumed under the older terms “modern” and “avant-garde.” This representative selection of works shows how far visual art had come from representation and expression to process-driven and idea-based work. The distillation of formal properties into a rigorously reductive vocabulary of marks and signs was a characteristic feature of conceptual work—whether it was photographic, language-based, or graphic.

Artists’ books are often associated with conceptual art. For some critics, the 1963 publication of Ed Ruscha’s now-classic photographic work, Twentysix Gasoline Stations, is considered the founding instance of “artists’ books” as a genre. In that framework, the distinctive features are photography, offset printing, and other mechanical means of production, including trade bindings. No gold fore-edges, no letterpress impression, no atelier images, and no fancy binding, paper, or traditional craft. In fact, as little craft as possible. Likewise, the contents consisted of affectless material—language or photographs–distant from personal voice or experience. The more boring, the better. Ironically, paradoxically, and with characteristic wit, the California conceptual artist John Baldessari once produced a canvas that was blank except for the words, “I will not make any more boring art” handwritten many times.

Other critics, including Brad Freeman, the editor/publisher of JAB: The Journal of Artists’ Books (1994-2020), and myself, have a broader conception of the origins of artists’ books drawing on many traditions of independent publication across a much longer history and array of varied practices. That is a discussion in which we have been engaged for decades.

But this small selection of artists’ publications issued by Schraenen is squarely within the 1970s conceptual framework. Their production values are careful, but minimal. They are projects by figures whose names and reputations became prominent within the networks of European conceptual art. All are thin volumes, one is a collection of fifteen postcards by as many artists and feature a line, shape, or other trademark graphic that would have identified their work as immediately for contemporary audiences as renowned conceptualist Daniel Buren’s signature stripes identified him. Branding, a matter of commercial identity and marketing, might seem to be far from the lofty zones of esoteric fine art, if it weren’t in fact so essential to its operations. But for conceptual and minimalist artists who reduced their formal language to the “least” thing, the recognizable brand was essential since it was the last remnant of aesthetic identity.

Who were these artists and why were they significant? Henri Chopin, for instance, was a musician and a visual poet, though, like many of these figures, he worked across media. Tape recorders and vocal manipulation as well as process-oriented improvisational technique featured in his sound compositions. Chopin also made films and worked in graphic design and related arts. His Wiki profile cites contemporary conceptual writer Kenny Goldsmith’s remark that Chopin can be seen as “a barometer of the shifts in European media between the 1950s and 1970s.” So can Schraenen, whose significance as a critic, curator, editor, and publisher is completely bound up with conceptual work across the media of sound, visual art, and, to some degree, performance.

Conceptualism emerged in the 1960s as an intellectual antidote to the expressivity of post-WWII abstraction and figuration (think Jackson Pollock and Wilhelm de Kooning in an American context, Karl Appel, Michel Tapié, and Jean Dubuffet in a European one). Conceptual art turned away from the direct expression of interior life to process-driven systems. Most famously formulated by Sol LeWitt in 1967 in his Paragraphs on Conceptual Art, “The idea becomes a machine that makes the art,” conceptualism tried to separate the work of art from the artist as a creative individual. Instead, a work of art was to be understood as a set of instructions, decisions, and ways of thinking about how to bring something into being. “Execution,” LeWitt added, “is a perfunctory affair.”

Conceptual art was not homogenous, any more than any other art movement before or after. But, like the other major movements of the 1960s and 70s, minimalism and pop art, it embraced fabrication, methods of production that bore no trace of the artist’s hand, and works that in principle could be executed by anyone (as per LeWitt’s wall drawings, created by instructions like “draw lines at right angles in three primary colors”).

Viewers seeking emotional content, cultural information, historical observation, or a depiction of the observed or experienced world often find conceptualism baffling and sterile. By contrast to the typical gallery-goer’s remarks about Picasso–“my child could have drawn that”, the response to conceptual work on the part of a general public is “How is that art?” A few lines on a canvas, a dangling string, a word on paper, a handful of geometric forms arranged in order—how, indeed, is this art?

These are ancient questions, moot and bracketed by the reception history of conceptualism in which the key recognition was that the idea was the most important element in a work of art. That, more than any of the formal strategies embraced by conceptual artists, remains a persistent tenet of belief within contemporary practices. Many of the current precepts were taken from the ur-conceptualist, Marcel Duchamp, and include “institutional critique” and the “strategies” of designating (“It’s a work of art if I say so”), signing, framing as ways of setting something (anything, hence the famous urinal, Fountain (1917), or the snow shovel In Advance of a Broken Arm (1915), and other canonical pieces). These are now so baked into art school and academic teachings that they form as absolute a foundation for art practice as life drawing did in Western art until the 20th century.

Much more of course can and has been said about conceptual art, but this brief summary is merely meant to situate the significance of Schraenen’s artist book publications. Schraenen knew everybody in the European circles who was considered important or critical in this domain and his editorial and exhibition lists read like a who’s who of the period.

As a final note, consider this aspect of the encounter with one of these books: Heisdieck’s Foules gives off a faint whiff of ancient cigarette smoke as it is opened. This barely perceptible sensation makes a direct connection to someone who exhaled in the presence of these folded sheets, probably fifty years ago when tobacco use was common and the book was being completed. Who smokes now, casually, socially, as a matter of course? Or in the workplace? The distance between those days and our own is as marked as the time gap that separates the appearance of conceptualism from its penetration into the ground water of contemporary art. That a book can hold such a material trace across time is a significant aspect of its very real physicality.

This handful of works was bequeathed to the editor of the Journal of Artist Books, Brad Freeman by Maike Aden after he met Schraenen in France in the 2010s. Now they serve as a reminder of connections made, networks established, and the value of books to consolidate those momentary relations in objects that endure.

Links to learn more:

https://www.guyschraenenediteur.com/

https://www.guyschraenenediteur.com/about-1/

https://www.journalofartistsbooks.net/