Art in the Newspaper Format

The Fluxus Newspaper 1964-1979 (New York: Primary Information, 2024)

Fluxus. More than half a century after many varied and dispersed activities were carried out by an international network of artists associated with this rubric, the name of the movement still provokes a certain bafflement. Unlike more descriptive terms from the 1960s—conceptual art, pop art, even minimalism–the term Fluxus, derived from the word flux (change), doesn’t immediately conjure a visual style. This is not surprising, since its activities were meant to challenge object-based art practices and concentrate instead on an experiential mode of participatory work. The curious after effect of this shift away from objects is that the emphasis on documentation became ever more important over time as the primary record of this broad movement.

Now, the publisher Primary Information has issued a facsimile of the Fluxus newspapers produced between 1964 and 1979. Through these crucial publications, edited at first by artist George Brecht and a “Fluxus Editorial Council” (whose title suggests more administrative heft and organization than likely existed), this group of artists consolidated their public identity. Why the newspaper format? In the 1960s this medium still occupied a significant place in public discourse. Also, newspapers had distinctive design features that made them easy to parody through appropriation. Playing with both facets meant presenting the art movement as if it were in fact (or sort of) news, though a quick look at the Fluxus newspapers reveals the irreverent attitude that wove through the group. The now canonical names of La Monte Young, Chieko Shiomi, Emmett Williams, Alison Knowles, Ben Vautier, Nam June Paik, and others appear regularly in the FluxFest programs (festival-like events that featured multiple artists). But a considerable amount of insider information is needed to decode the references and figure out who is who in photographs and off-hand citations.

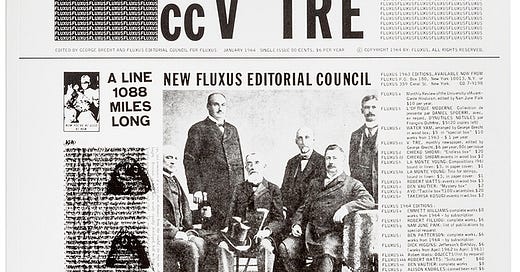

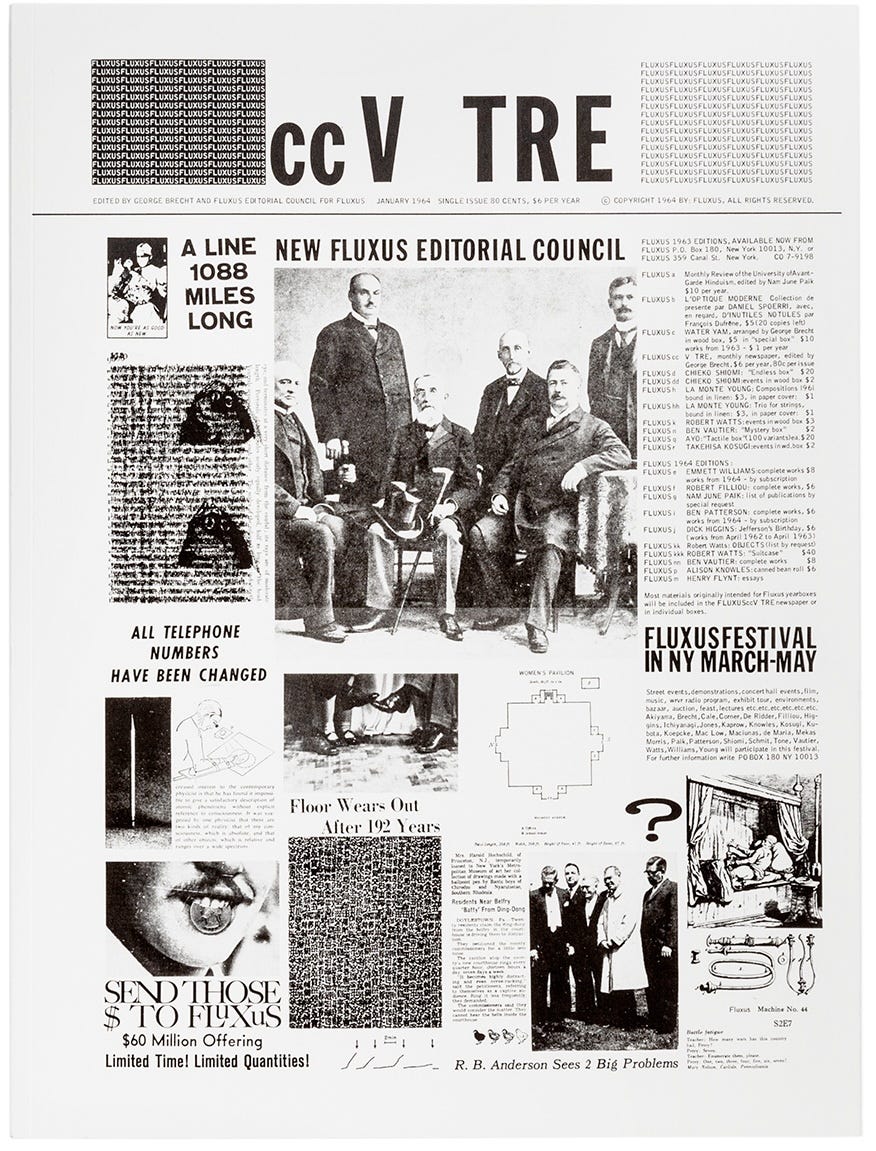

cc V TRE, Volume 1, Number 1, 1964; photo courtesy of Primary Information

Issued in tabloid format, these papers originally provided a platform on which to advertise such events and ongoing activities. But the newspapers were also meant to be works of graphic art. With their grainy black and white photographs, variety of headlines, multi-column layout, and regular masthead they could have passed as the newsletter for any community organization. But the anomalous nature of the contents quickly becomes apparent. They are filled with cut-and-paste collage materials from a whole range of sources, including 19th century advertisements, photographs, and strange juxtapositions of text-and-image pairs. Actual documentation about the Fluxus movement and its activities appear right next to items such as an engraved advertisement for Victorian devices to cleanse the colon and lower intestine, another for a self-tipping mechanical hat, or news items that have been clipped and culled from other real (or fake?) news sources (e.g. “The Floor Wears Out After 192 Years”). Though identifiable as a group when taken together, each individual issue had its own bespoke style.

In the history of modern art, the newspaper has only occasionally served as a site of direct engagement. Even more rarely have artists made newspapers as art. The publication of the Futurist Manifesto in the Italian Gazzetta dell’Emilia on the 5th of February, 1909, and then on the front page of the French journal Le Figaro two weeks later, February 20th is notable. Using the highly visible location to promote the agenda of the newly formed movement, Italian Futurism’s founder, Filippo Marinetti, had authored the text as a declaration of principles and agendas. Inflammatory in tone, the Manifesto was a deliberately provocative gesture designed to shock the bourgeois readers of the paper in which it appeared.

Precedents for Marinetti’s action had appeared earlier in the 19th century. Gustave Courbet, who painted gritty images of workers, for instance The Stone Breakers, 1849-50, had issued a Realist manifesto in 1855. And the Symbolist writer, Jean Moréas had also used Le Figaro as a publishing platform for his manifesto text in 1886. Manifestos deliberately borrowed from the rhetoric of the most famous example of all, the Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, making the link between aesthetic and political positions explicit. The theme of “revolution” was applied to art making as a practice in which radical gestures were believed to both express and bring about transformations of culture. While manifestos provided succinct templates for the tenets shaping any artistic movement, they had far less impact on the political realities of their times. Marinetti’s flamboyant rhetorical embrace of speed, machines, and electric light may have spurred artists towards depictions of these phenomena, but probably did nothing to influence industrial production, address labor issues, policies around pollution or safety, or even public opinion—let alone political action. The long history of the illusion of political efficacy of artistic practices is a tale to tell elsewhere another time.

Newspapers in art, not just platforms for publicity and promotion, have their own place in art history. As actual material, they show up in collage production across Dada, Cubist, andFuturist practices in the early decades of the 20th century. Their depiction—as in Pablo Picasso’s collages and Cubist paintings—was a sign of modernity, immediacy, the banality and reality of daily life. Nothing passes in and out of relevance as quickly as the news. The daily press, in its modern mass-produced form, was an early product of industrialization—the famous high-speed steam-driven printing presses that pushed the London Times into widely available circulation were introduced in 1814. The role of newspapers in modern life tracks back further, and the role of public discourse is well-documented from at least the 17th century, with widely circulating newssheets and ballads appearing already a century earlier. These publications included many that were explicitly political—from satires of figures in the Catholic Church, caricatures of royalty, calls for revolutionary action through such renowned examples as John Dickinson’s “Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania” published anonymously in 1767-8, and of course scandal sheets provoked by crimes and passions.

Newspapers served and still serve as instruments of influence, as well as for the regular reporting of events constructed and/or accounted for through print and now digital media. But the production of newspapers as art has resulted only in a small, rarified corpus. By the mid-to-late 1920s, the Surrealists issued publications that masqueraded as mainstream journalism, with La Revolution Surréaliste as one striking example, issued with masthead and in Volume and Number, grainy black and white photographic images displayed on its cover page. The Surrealist group also imitated scientific journals and other formats as part of their games of aesthetic mimicry in which the aspiration to legitimacy and authority is evident.

For the Fluxus group, the use of the newspaper format allowed the artists to present their events and material with a Monty Python tongue-in-cheek dare to the reader who is challenged to a constant “believe it or not” contest in reading. Monty Python’s Flying Circus, which animated many of the same kinds of Victorian advertising materials to humorous ends, did not appear until 1969. 1960s Pop art appropriations included plenty of nostalgic citation of older styles. Milton Glaser and other designers of the era involved with Push Pin Studios, founded in New York in the 1960s, were fluent in earlier work by Aubrey Beardsley, Will Bradley, Art Nouveau and Deco work, but also the imagery and flamboyant typography of 19th century poster design which they cleverly copied and recycled. Appropriation was greatly aided by the technology of photomechanical reproduction. The Fluxus newspapers would have been created with scissors and paste to produce “camera ready” copy. Anything could be cut and added to the mix, provided it could be printed in black and white. The reproduction of borrowed half-tone photos made for grainy images, since reprocessing them with another half-tone screen would have resulted in moiré patterns. This knowledge is all part of forgotten lore in the print industry where darkroom copy cameras took up an entire room and the skills to use the equipment required apprenticeship training.

The discussion of production methods is relevant because somebody had to design and produce these sheets, including typesetting the often extensive copy in an era long before personal computers were available. Dick Higgins, founder of Something Else Press and one of the major figures in Fluxus, had considerable expertise in the graphic printing arts. His young jaw smiles below his moustache on the front page of the first edition. He has a coin in his teeth above the statement, “Send Those $ To Fluxus” after which, “$60 Million Offering / Limited Quantities.” The item mocks the Fluxus emphasis on non-commercial, even non-commodifiable, aesthetic practices.

Since the main focus of much Fluxus work was the creation of participatory activity—engaging viewers as active agents–the games played with readers make sense. Fluxus was dedicated to the blurring of the line between art and life. This meant that organizing and orchestrating utterly banal events—turning your car lights on and off several times, pouring water from one glass to another—that anyone could do was a frequent activity. Largely inspired by the experimental composer John Cage, whose classes at the New School in New York had been attended by several of the key Fluxus founders, these were actions meant to call attention to ordinary life, to experience, rather than material form as a fundamental feature of art. Fluxus had much considerable overlap with conceptual art of the 1960s, much of which was “de-materialized”—created as instructions or documents rather than as objects. But Fluxus was also, as per Higgins, one of its articulate spokesmen, engaged with “intermedia”—a term he coined. Here is where the newspapers come in because these Fluxus works are not simple reports in the newspaper format, they are newspaper works as art. The distinction is important.

Titled cc V TRE, an enigmatic name variously played across the series of issues (cc Valise TRianglE or Vacuum TRapEzoid), the newspapers are filled with insider jokes and references. Many individuals are identified, many are not. The appropriated advertising styles are put at the service of utterly obscure or only-those-in-the-know-would-get-it notices in which the “Come One Come All” invitations might have led the unsuspecting viewer to an event watching someone tapping on glasses with a spoon in one’s teeth or seeing a woman holding a brush with her genitalia to create a gesture painting on a canvas. Yes, those were the days. Fluxus artifacts are advertised as well and one could order “Dirty Water” in bottles, a “Finger-Box” by the celebrated artist, Ayo, then selling for $20, now a museum object, or a “Collection of Holes” that included photographs and “actual holes” in a plastic box for $5. Was this marketing of Fluxus merchandise a paradox for these artists who claimed to eschew the market in objects—or was it a critical statement demonstrated by selling apparently anti-aesthetic objects? All of these are now much celebrated, written about, and known artifacts of the Fluxus movement and the newspapers provide a rich documentary record of their appearance, production, and circulation.

Primary Information, the publisher that has issued these facsimiles, has been publishing new artists’ works and facsimiles of historical books for almost two decades, making artifacts like cc V TRE and the other Fluxus publications available. Their goals are to support work at the intersection of art and activism through a systematic editorial program. This volume is beautifully produced, carefully designed, printed, and bound. No preface, critical or scholarly introduction or afterward has been added. The facsimile reproductions are meant to be engaged directly. Some eyewitness testimony might have added another dimension (and add comprehension) to the volume, but the handsome production is valuable for the access it provides to these rare materials.

What struck me most about the volume, as already mentioned, is the combination of in-crowd communication and historical character. Newspapers. Who now would imagine, as an artist, that the print newspaper is a site for significant exposure or that its forms were—are—those of influential communication? This artifact marks the distance between the 1960s and the present through the attention it calls to changes in media practices. In addition, the playful, irreverent inventiveness feels unconstrained by dogma or ideological orthodoxy in ways almost impossible to imagine in our current climate.

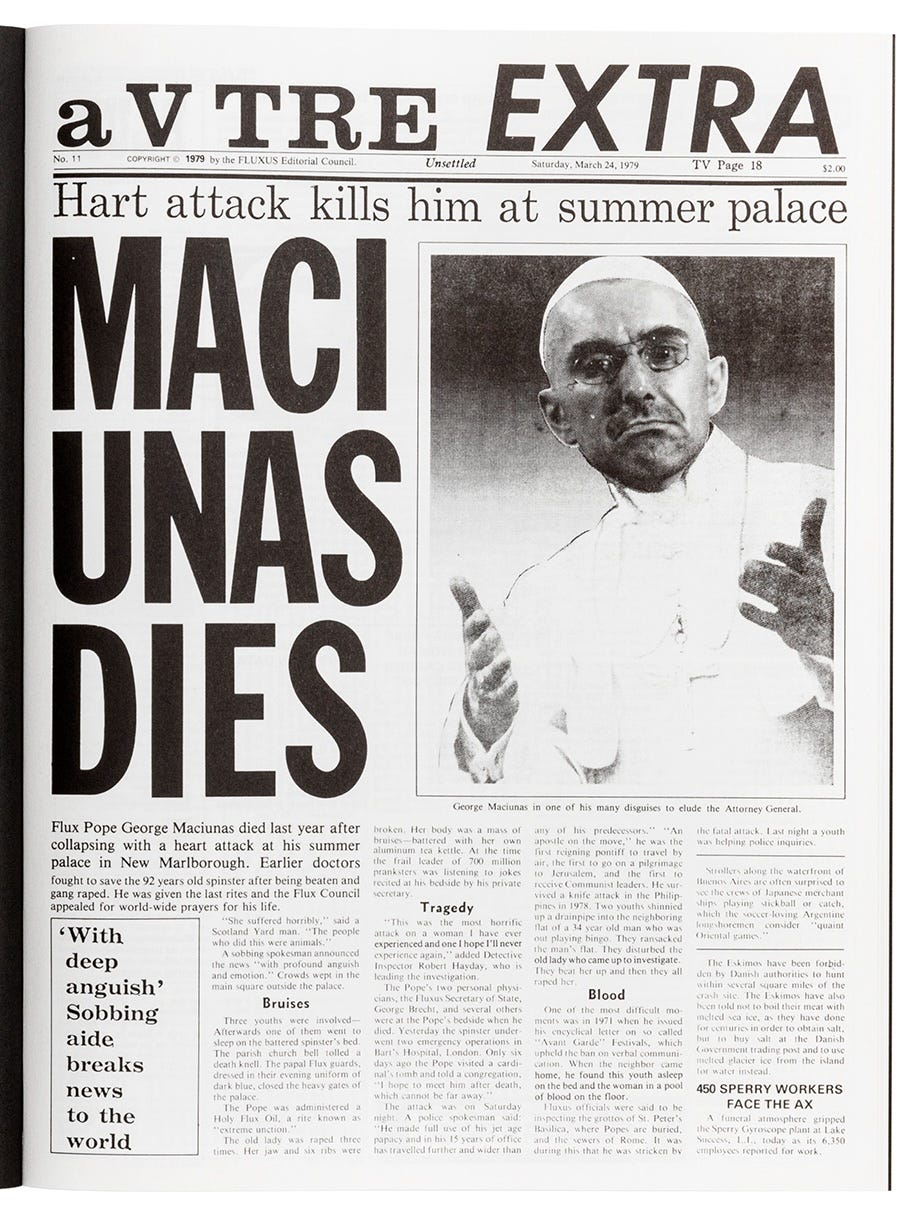

1979 issue of cc V TRE. Photo courtesy of Primary Information.

Perhaps the most poignant issue in the collection is the one that appeared in 1979, a year after the death of George Maciunas. The Lithuanian-born artist was a major figure in Fluxus who unfortunately died in his 40s from pancreatic cancer. The headlines of the commemorative issue state, “Maciunas Dies” and the story begins, “Flux Pope George Maciunas died last year after collapsing with a heart attack at his summer palace in New Marlborough. Earlier doctors sought to save the 92 years old spinster after being beaten and gang raped. He was given the last rites and the Flux Council appealed for world-wide prayers for his life.” The story blends fantasy, fact, and outrageous fiction in an indiscriminate mélange while the rest of the issue mixes stories like “California Posse Hunts Woman Reported Carried Off by ‘Big Foot’,” “Cook Meets Untimely End,” and personal commemorations by such renowned Fluxus colleagues as Henry Flynt. The story headlined “Man Gives Birth to Gorilla Twins” is accompanied by a photograph of two parrots and the issue is filled with photographs of Maciunas’s marriage to his longtime girlfriend, Billie Hutching a few years earlier. A very human document, this album of photos straddles the line between the life of artists as public figures and their private experiences and existence. At a moment when tabloid press reports were the means by which such negotiations were made, the Fluxus artists chose this form as a significant mode of art making to commemorate their own milestone moments.

So much has changed. An innocence we no longer possess permeates these pages even if, at the time, we did not see it clearly enough to imagine it would be lost.