I had no previous knowledge of the 20th-century poet-composer-artist Altagor (1915-1992) until I encountered his work in this recent exhibit organized by Frédéric Acquaviva in collaboration with Alain Oudin. Access to the exhibit involved a very-Parisian set of entry maneuvers: punch a code (obtained in advance) into the keypad, step through massive outer doors onto the cobblestones, cross three interior courtyards of what looks like an abandoned factory for light industry from early in the last century, and then arrive at a yellow sign on a staircase in the shadows at the far end of the yard before descending to the basement. There I found myself in a clean, bright, well-organized white-walled gallery. Though the exhibit is open to the public, I felt like I had gained a privileged entry to a rare esoteric experience.

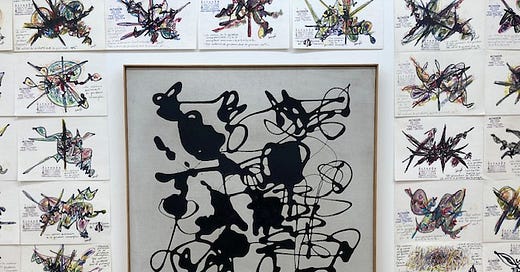

Altagor, Paintings.

Acquaviva and Oudin generously provided elaborate commentary on Altagor, his life and his work, as we walked through the exhibit. Acquaviva is best known as a No Wave composer, but he has written extensively about the French experimental poetry of Lettrism, its principal founding figure, Isidore Isou, and regularly contributed to the scholarship on the 20th century avant-garde. Though little of this material has been translated, his research remains a major source of information about these figures and movements. Oudin, the founder and director of the Enseigne Oudin, gave me a glimpse into the varied research materials available for study at the foundation. His expertise in conceptual art, artists’ books, visual poetry, and avant-garde work has guided his collection and exhibition strategies. These conceptual works are intellectual, refined, and often quite minimal, rooted in attention to material and process more than lyrical or personal content.

Altagor is far less known than some of the Lettrists, sound poets, and experimental musicians who were his contemporaries in the 1960s and 1970s—and many of them, though known within certain communities, are still relatively obscure.[1] When I queried some of my colleagues in France and the US who are well-versed in 20th century French poetry, they were mainly unfamiliar with Altagor as well. This immediately raises questions of course about whether a figure whose work was relatively obscure during their lifetime and has had little impact, subsequent critical attention, or influence can be significant half a century later? Reception is critical to an artist’s legacy, but work with a substantive core merits attention and sometimes revival. My brief encounter with the sheer systematicity, cross-media fertilization, and elaboration of method in Altagor’s practice convinced me that his work is fascinating within the mid-century European context. Whether that interest goes beyond the historical case will probably depend on future research and critical study of his work.

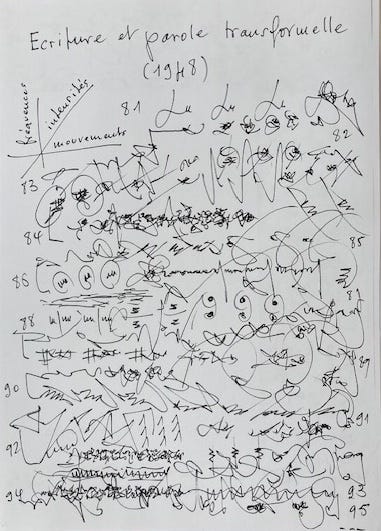

Altagor, notation system for “metaphonic” composition.

Enseigne Oudin is separated into several connected gallery spaces, an office, and a research reading room. The galleries were filled with Altagor’s paintings, papers, hand-made musical instruments, and a mass of documents. Acquaviva began his introduction with the small cases containing biographical material from the artist’s early life. Born in 1915, André Vernier took the name Altagor in part as an act of separation from his childhood roots and identity. Originally from Moselle, he started working in mines at the age of 14, a situation from which he wished, understandably, to extricate himself. A gifted intellectual and artist, auto-didact, and composer, Altagor developed several unique and idiosyncratic methods for composing, scoring, and presenting his works. Perhaps the most compelling aspect of his work is that he created systems that blended poetry with music through graphical means. This elaborate synthesis was evident in in various paper scores and typewritten manuscripts where his “meta” approaches became articulated. He made extensive recordings (reel to reel tape) and his frequent radio appearances in the 1950s and 1960s were crucial to public dissemination of his works.

The typed and hand-written artifacts have a richly authentic quality as original carbon copied typescript, hand-written pen and pencil, scribbled ink and overlaid paint. Altagor was prolific, and much of his poetic archive was acquired by Yale’s Beinecke Library where it is available for research, but hundreds of other items were on view in the gallery. These included posters, notices, and other ephemera documenting moments when he had a visible profile. In addition, there was a collection hand-made instruments crafted from simple wood and strings. One, originally strung with rubber bands, did not survive the dessicating ruin of time. But the others—pantaphones and plectophones as he termed them—formed a sculptural core in one part of the gallery. Minimal, undecorated, and geometric in their basic volumes, the instruments have a commanding presence. Listening later to recordings online supported the impression that they were designed to work with a stripped-down aesthetic of clear clean notes and distinct sounds.[2] Around them, on the walls, were vivid, graphically striking, scores that suggest a wide range of possibilities.

Altagor, handmade musical instruments.

Altagor chiefly identified himself as a sound poet and composer, though the graphic features of his work as well as his paintings reinforce the multi-media aspect of his profile. Many of the works on paper are either scores or notation systems, articulate and elaborate signs, glyphs, and arrangements clearly marked in the artist’s unique script. These are composed according to a carefully worked out scheme of Altagor’s invention.

Altagor used the term “metapoésie” (metapoetry) to describe his own approach. Like the Dada and Futurist and other innovative modern poets who had preceded him, he was particularly interested in the ways such work could salvage language from its banalization in everyday use. Poetry in its standard forms still relied on the words used in ordinary life, and by breaking language into its material components, Altagor aimed to revitalize it at its foundations. He understood poetry as sonic energy, vibration, frequency, and intensity put in the rhythmic patterns and forms.

Altagor, Transformelle work.

He also invoked the concept of “transformal (transformelle)” work, a mixed modality of graphism and sound. In these works his rhythmic strokes and patterns appear, gestural, but not as mere expressions of somatic activity. One long suite of pages in neatly slanting black strokes carried scansion/scoring notation below every line. The subtitle identified this as a “prosodique, analogique, et synthétique” (prosodic, analogic, and synthetic) work. The text is phonetic, not semantic, “ologhuoze issodola” and so on. One sheet, numbered “page 508,” gives an idea of the extent of this work, and the confident hand in which the piece was written also suggests a well-developed practice.

Altagor was not alone in the context in which he worked. Other major sound poets and musicians experimenting with unstructured composition and radical approaches to the material of language and sound were working at the same time. Among them, Henri Chopin is one of the best known, but Altagor’s scores can be compared with those of John Cage as well. Altagor had shifted from earlier, more conventional approaches to his more radical innovations by the 1940s, though dating Altagor’s work and compositions is a task for a dedicated researcher as he was not always consistent, apparently, in this regard.

Overall, the material in this exhibit was filled with a certain manic energy, or at least, an incredible drive that resulted in a veritable torrent of production. Sheet after sheet of typewriter paper bears witness to his commitment to elaborating his vision. For instance, one carbon copy of a typescript page presented a full table for vocal analysis of sound units meant to serve as exercises for “Diction Polyphonique.” This list of consonant-vowel combinations is exhaustive, the work of someone doing an intensive analysis of the combinatorial possibilities of language. That was just one sheet among hundreds.

Altagor, notes, compositions, theoretical sketches

Altagor used the typewriter as a composition tool, but many of his graphic works are hand-drawn. The elaboration of a full system of notation, displayed on the wall near his instruments, was completely worked out. Even with no knowledge of how he used it in his own work, a viewer can sense the conviction with which it was created. No doubt seemed to trouble his work, and no hesitation. A work with the title “absolute art / final mutation / variations without end” is not presenting an idle claim. He believed that figuration and representation were alienating, that they prevented the reality of poetry/sound from appearing by dressing it in the guise and fiction of a symbol. Freeing art from this fiction was his goal, and he pushed towards it constantly.

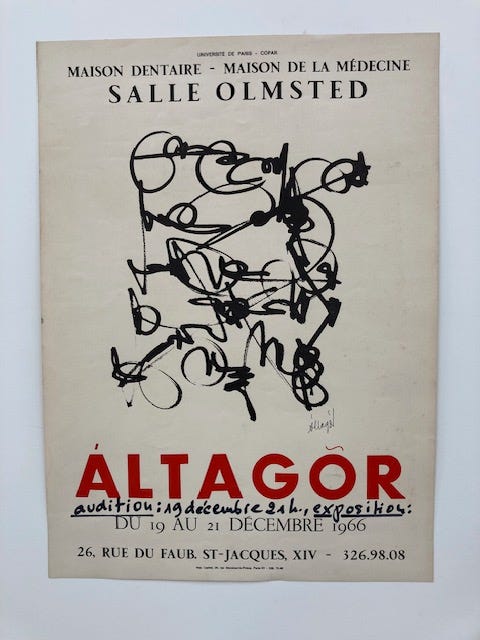

Poster, 1966, announcing an exhibit

The 1960s were a peak moment for Altagor in terms of reception. He exhibited at galleries, was a recognized poet-musician in radio broadcasts and performances. The record of these activities is evident in the gallery announcements and other ephemera, the all-important material witnesses. Like many other artists active in Paris in this decade, Altagor had his encounters with the Lettrists and wrestled (figuratively) with Isidore Isou, the contentious founder of the movement. Claims to priority of invention put them into conflict, but also, ambitions for recognition of the value of their work. The glyphic quality of Altagor’s drawings clearly resonates with those of Isou and other Lettrists, and sorting out who invented what feels less important at this distance than recognizing the incredible currency such approaches had at the time. Sharing some of the spontaneity of automatic writing in Surrealist work, and the gestural vocabulary of someone like Brion Gysin, these graphics were visible across the landscape of mid-20th-century arts. The paintings have a spontaneous energy to them, but each has a vivid animate quality. Assembled together on a wall they look like a mass of strange biomes, microscopic animals each unique and alive, throbbing and pulsing with activity.

Throughout his life, Altagor carried with him a fantasy of ideal love in the image of Simonia, a female other he imagined as his perfect other, soul mate and partner. He wrote for and about this fantasy, guided by the imaginary muse, always searching. Clearly he derived some focus and inspiration from this process, and drawings of the imagined figure as well as dedicated compositions weave through his work.

Eccentricity is not a guarantee of genius, in and of itself, any more than genius is necessarily marked by peculiar habits in spite of original thought. But in the case of the artist-poet Altagor, the two came in striking combination. Altagor, and the extensive corpus of his work, remains nearly unknown within the references where such obscurities are usually marked. Curiously, as the curators note in the small checklist pamphlet accompanying the exhibition, he is mentioned in a passage in the work of Robert Bolano, himself an individual with a unique profile. In the Bolano reference, as per the pamphlet, Altagor appears in the company of other well-known artists in an imaginary encounter—all of which feels fitting for his elusive enigmatic figure.

How important is such an artist? In many ways, he was an outsider with a unique and well-developed aesthetic. He left a pile of papers, mass of paintings, and various drawings, theoretical texts, and other evidence of his elaborate thought processes. Do we recover such a figure simply to engage with and appreciate their vision? Their elaborate systems? Or to imagine that somehow his work will inspire and influence artists of another generation? Or as a curiosity? Unclear. But it was an exhilarating experience to find these complex scores and elaborate works and to think about how his approach defined a particular set of aesthetic possibilities—some of which may be yet unrealized.

In the photographs he appears lean, sinewy, determined. No excess or slack, no ease or softness appears. He has the face of a deeply focused man, intent on realizing his singular vision. Autonomous and singular, he fell into obscurity by the end of the 1970s, though he continued to work until his death in Paris in 1992. Was he lonely, bitter, angry, feeling neglected and unappreciated? Hard to know, would he have welcomed more recognition? Quite likely. Not up to me to project onto Altagor how he felt about his “career” and his life. I felt a combination of inspiration and despair in response to this exhibit, an exhilaration at encountering the work and spirit, and a sadness at the obscurity into which so much of what he had created with such passion has fallen.

Thanks to Frédéric Acquaviva and Alain Oudin for their insights, information, and Enseigne Oudin for permission to take the photographs that appear here.

[1] Sound poetry is an esoteric form, relying on performance and an audience interested in non-semantic or a-semic articulation. Sound poetry flourished among Dada poets where its import was loaded with political associations—the refusal of meaning, like the attack on reason, was meant as a rejection of dominant and mainstream compliance with the aims of what were perceived as capitalist agendas driving the First World War. Dada poets used a version of “ransom note” typography to create visual cacophony. Sound poetry also had adherents among the Russian Futurists, particularly Velimir Khlebnikov and Ilia Zdanevich, both practitioners of zaum, a “transmental” form that was intended to communicate through affect rather than semantics. Zdanevich created a mode of visual scoring and typographic innovation to infuse his works with sound values. A vital tradition of sound poetry also arose in Italy in the 1970s and 80s as well as in Canada. Many of the writers associated with these activities were also affiliated with visual and graphic poetry. Altagor is clearly among them as evidenced by his interest in an invented language of glyphs and scores. Not every visual poet was a sound poet, and vice versa, but the interest in invention at the edge of poetic form characterizes both modes.

[2] Many are now in the collection at the Beinecke Library at Yale https://archives.yale.edu/repositories/11/resources/10776 See also: https://www.postwarcultureatbeinecke.org/copy-of-jacqueline-de-jong

Recordings available online include those at Ubuweb.

I hope these essays will be published as a book.