Alessandro De Francesco, Unstable Orbits

(Bern: edition taberna kritika, curatorbooks series, 2025

What are the dimensions of human experience–and how would a graphic language express the complexities of ambiguous emotional conditions? Painters and sculptors, artists of dance and movement, are all capable of portraying and evoking the full range of tragic and comic events. We are familiar with the agonies of loss, scenes of tearing hair, pounded chest, and exuberant joy depicted in bodies and landscapes suffused with light and shadow. But graphs and charts? Beyond parody or reductive statements, the conventions of scatterplots and geometric shapes are rarely pressed into the service of poetics. Why?

The intellectual lineage of these conventions works against them. They emerged from the natural sciences and got kidnapped by the social realms of statistics, demographics, and other activities as useful but mundane conveniences whose curves, spots, and lines have been adopted precisely because they seem outside the realm of subjectivity.

So how remarkable to see the appropriation of these shapes and combinations into a work of lyric poetry in Alessandro De Francesco’s fully engaging book, Unstable Orbits, where every page is a thought experiment in the ability of schematic form to embody rich poetic statements. While some precedents exist, they are few and far between (the errant lines describing the narrative meandering of Tristram Shandy, Taking a Line for a Walk by Paul Klee, various cartoons of Saul Steinberg, and so on), and De Francesco’s project moves past mere novelty into a sustained demonstration of diagrammatic work. The forms in Unstable Orbits are not all the hard-edged geometric ones of information visualization, but here again the history of visualization methods becomes entangled with mathematics in its pure and applied forms.

To take a significant example, before Johannes Kepler wrestled with the discrepancy between planetary orbits and their representation in graphic form, the unquestioned and prevailing belief was that the motion of the celestial bodies had to fit the shape of a perfect circle. No Divine being would have created orbits that deviated from perfection. By definition, any differences from a circular orbit had to be explained by errors of observation—or compensated for by the creation of diagrams that had elaborate systems of circles mounted on the rims of other circles of smaller and larger dimensions. Even Nicolaus Copernicus’s revolutionary model of a heliocentric solar system (first published in the 1540s) was diagrammed with the epicycles whose circular perfection can be used to calculate the appearance of elliptical orbits. If putting the sun in the center of the system was radical, using elliptical forms would have been equally heretical. Only one tenet of belief in Biblical accounts of Divine construction could be altered at a time.

But Kepler, with Copernicus’s system already a reference, if not a fully accepted model, could modify the mechanism with mathematical calculations that accurately described the elegant off-center proportions of an ellipse. From that point on, the workings of planetary movement could be explained—and their motions be used to explain other phenomena as well. Imagine, a well-regulated and regular path of motion around a sun that was located off-center in the orbit. The implications were complex, and Kepler had to work out the variations in speed of motion in the close and distant segments of the orbit as well as the differences among the rates of movement of the different planets. From a model of a mechanically perfect celestial machine, we are suddenly shifted into the complexities of what looks more like family life. Everyone moving at their own pace, occupying different positions in relation to each other at different times, some with their faces turned permanently away from the source of light and illumination, and others—well, you see the issue. Perfection? Of a sort, but more variable, more idiosyncratically diverse, and more interesting than mechanical perfection.

I introduce this bit of history into the discussion of Alessandro De Francesco’s engaging Unstable Orbits because the graphics of his poetic works resonate so strongly with the deviation from perfection Kepler managed to describe. De Francesco’s system is the human world, emotional, personal, projected and introspected at the same time. The individual works are deceptively minimal, their allusive provocations far more profound than the schematic presentations at first suggest. These are diagrammatic poetics, graphic and linguistic equations that inscribe exceptionally complex situations with an elegant efficiency of means. Some are amusingly clever. Others are poignantly moving.

But, throughout, De Francesco makes use of the conventions of charts and graphs. The first poem is mapped onto Cartesian x and y axes, as if the variables of language and emotion could be tracked with these means. Descartes created the coordinate system that rationalized the surface of a plane, an innovation so profound it now passes as natural that two variables could be plotted against each other in this way. The apocryphal tale is that the 17th century philosopher was lying in bed watching a fly on the ceiling and pondered the possibilities of finding a reliable method for locating its position. He succeeded and coordinate systems in two dimensions (and three and so on) met with such success that we might be forgiven for imagining that the space of the world itself conforms to these conventions.

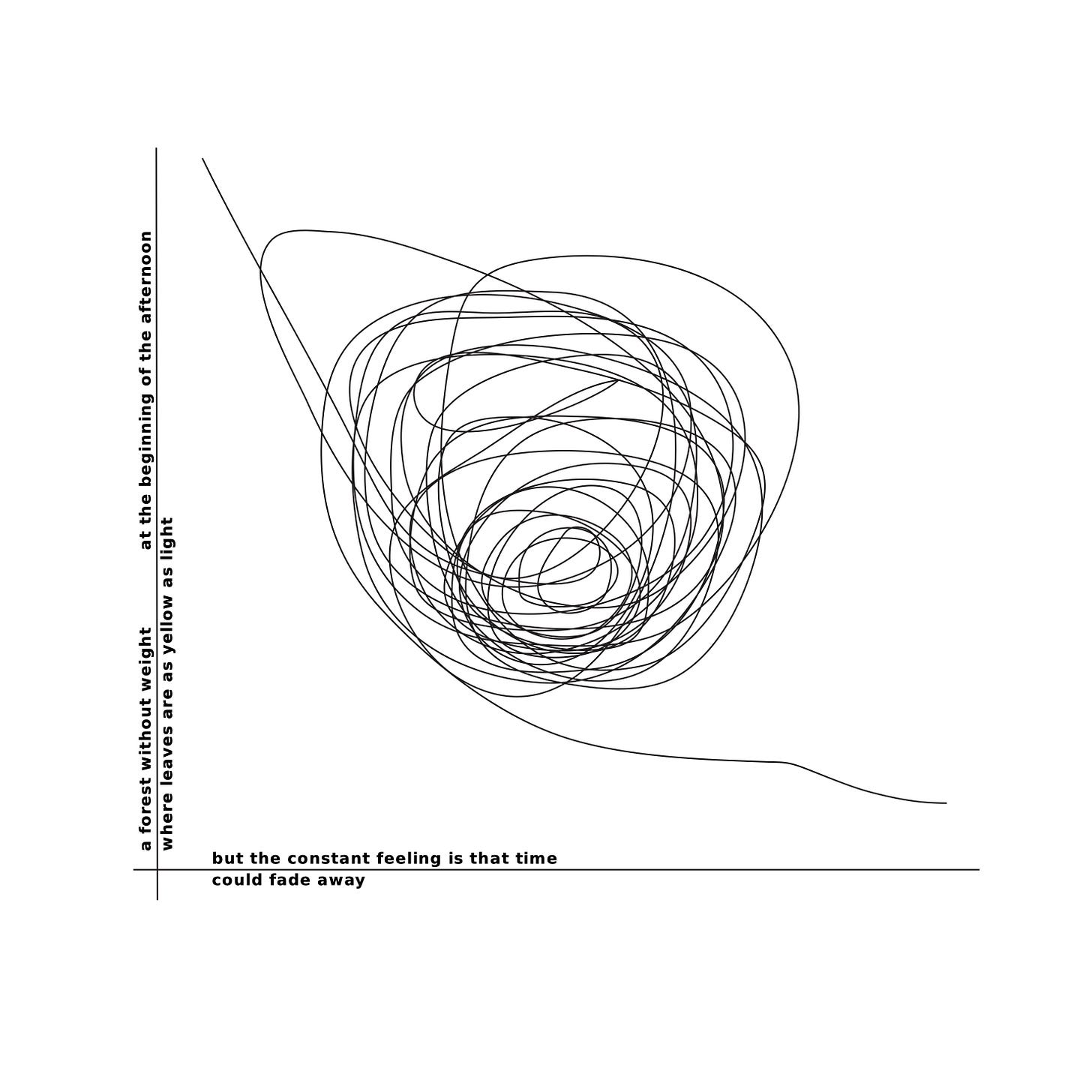

De Francesco appropriates this rational system to poetic ends, as in this first poem in his book (above). The statement on the y axis has a concrete reference, imagistic, and specific:

a forest without weight at the beginning of the afternoon

where leaves are as yellow as light

The bold sans serif type has a deliberate intentionality, the statement solid, compact, and clearly placed above and below the line. By contrast, the phrases on the x axis allude to temporal dimensions:

but the constant feeling is that time

could fade away

This division is in keeping with conventional graphing where the x axis is often used for time scales–the left to right direction reinforces a sense of linear arrow inherent in human temporal perception. In the plane between the curving line circles about itself repeatedly, entering and exiting the field at upper left and lower right. The drawing is based on an actual unstable orbit diagram in which a body, planet or moon, enters an orbit and follows it for a million years or so before exiting. As the artist commented (in email correspondence), this is “a wonderful representation of a cosmic unpredictable complex system.” The result is that the two stanzas define a concrete and an ephemeral dimension respectively and the drawing enacts the transient character of the situation.

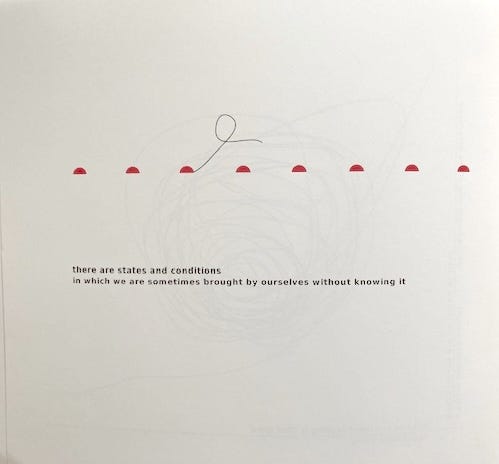

Turn the page and across the opening are two graphs using a language of red and black circles and black lines. A row of half-circles high on the page with a single irregular looped squiggle rising from one is accompanied by:

there are states and conditions

in which we are sometimes brought by ourselves without knowing it

Without the graph, the poem stands, but with the graphic components, it shifts gear, becomes a conundrum, an idea to contemplate with reflection, no longer a simple statement but instead, a provocation.

The skill in these works—there are a hundred in the book, one to a page—is in their use of schematic, non-representational forms to oscillate between concrete and allusive values. The statements often refer to things perceived (“the flowers outside the opaque shadow moving”) but also many conceptual formulations (“a shapeless mass” or “the deepness of space”). Certain thematics emerge, with attention to space, events, skin and surface occurring repeatedly. Interspersed with these are lyric cries, the voice of yearning, as in the poem on page 19 whose only line, “please come home,” is accompanied by a scatterplot of black dots within a thin black frame. The outliers to the massed dots become charged by the call, as if the center of gravity has not held steadfast enough to keep them.

Every page of this carefully made book, printed on thin coated stock that holds the detail of the print very sharply, is thoughtfully considered. In his final note, De Francesco makes the point that “every orbit is unstable” if observed long enough. The erratic deviations from any apparent regularity eventually unravel the order of things. “Every gravitational relation will come to an end.” But in the meantime, “we fill this void with our presence,” as “a part of all there is” since “we belong to being.” The upshot of reading these poem-diagrams is the recognition that the profound dimensions of human perception and emotion may reside in the most distilled expression as surely as in the most replete.

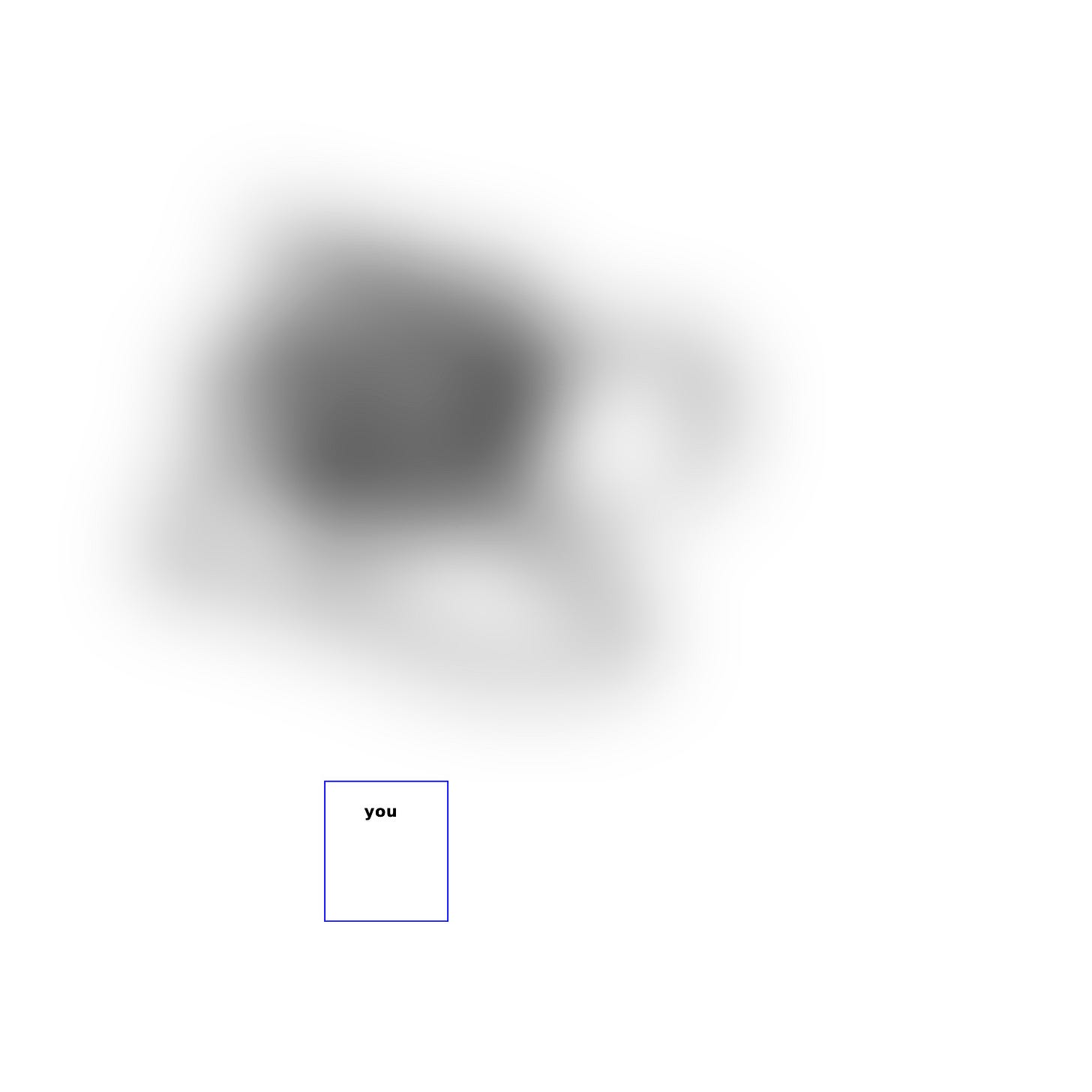

Each work has its effect, but among them, one of my favorites is the page on which a dispersed and vague cloud is accompanied by a framed word “you.” The juxtaposition forces us to consider the complexity of direct address, the formation of a spoken subject of an enunciation, who is, always, a projection that cannot be finally defined. The work also shows the important of the whole book as a context, since this provoking image/text benefits from being among other allusive and suggestive works where its deceptive lightness of touch cannot be overlooked.

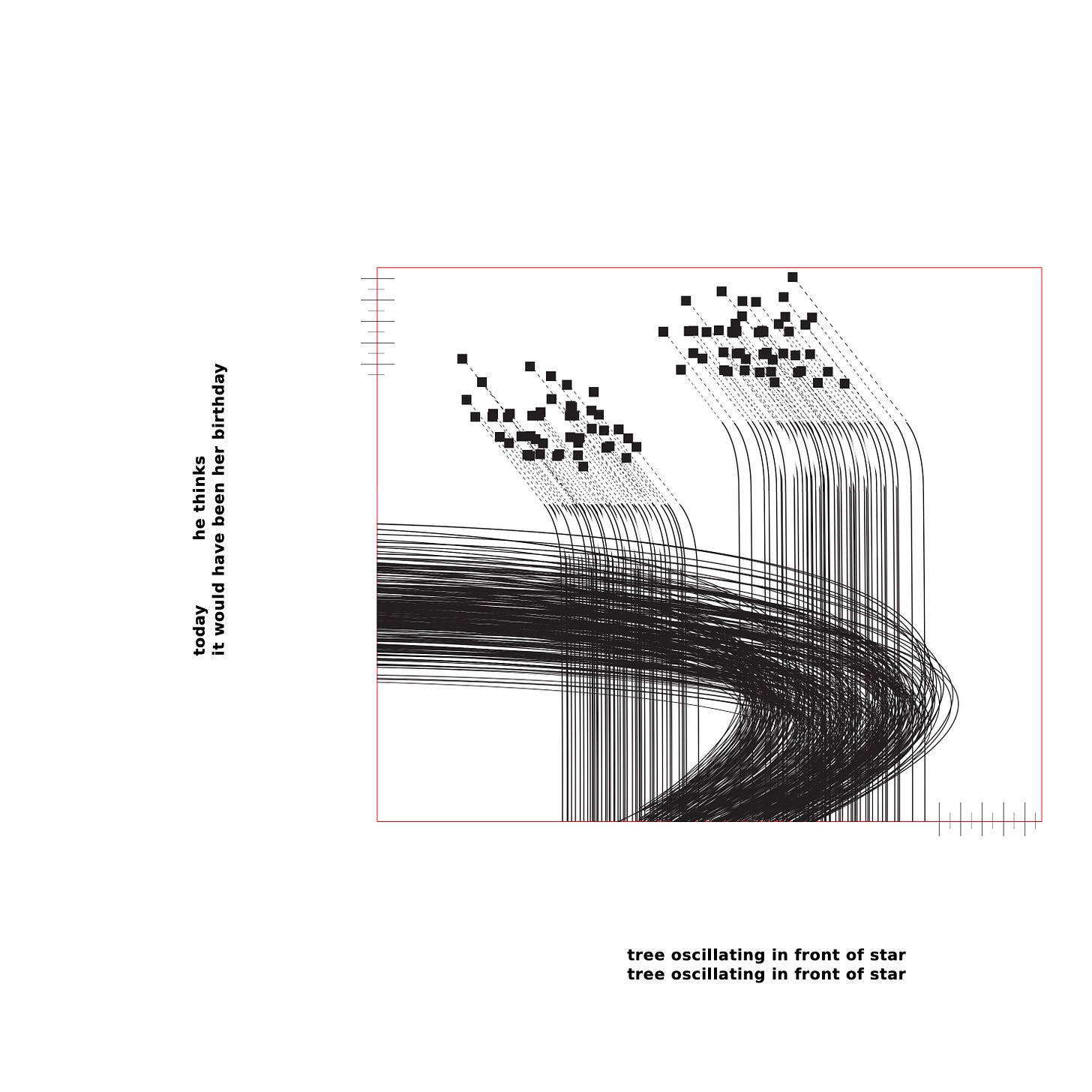

Rather than read these individual works, I present a few more of them to be viewed.

All images reproduced by permission of the artist/poet. Some of these works were exhibited at ETK / Dreiviertel art space in Bern in a larger format as part of the book launch.

To purchase a copy: https://www.etkbooks.com/alessandro-de-francesco-unstable-orbits-curatorbooks-014/;